Health & Medicine

Allergies, food labelling & saving lives

The current treatment for coeliac disease is a gluten-free diet, but researchers want to ‘train’ the body to tolerate the toxic gluten protein as a new way to treat the disease

Published 18 March 2019

As a boy with a peanut allergy, Dr Jason Tye-Din knew from an early age that food could kill, as well as cure.

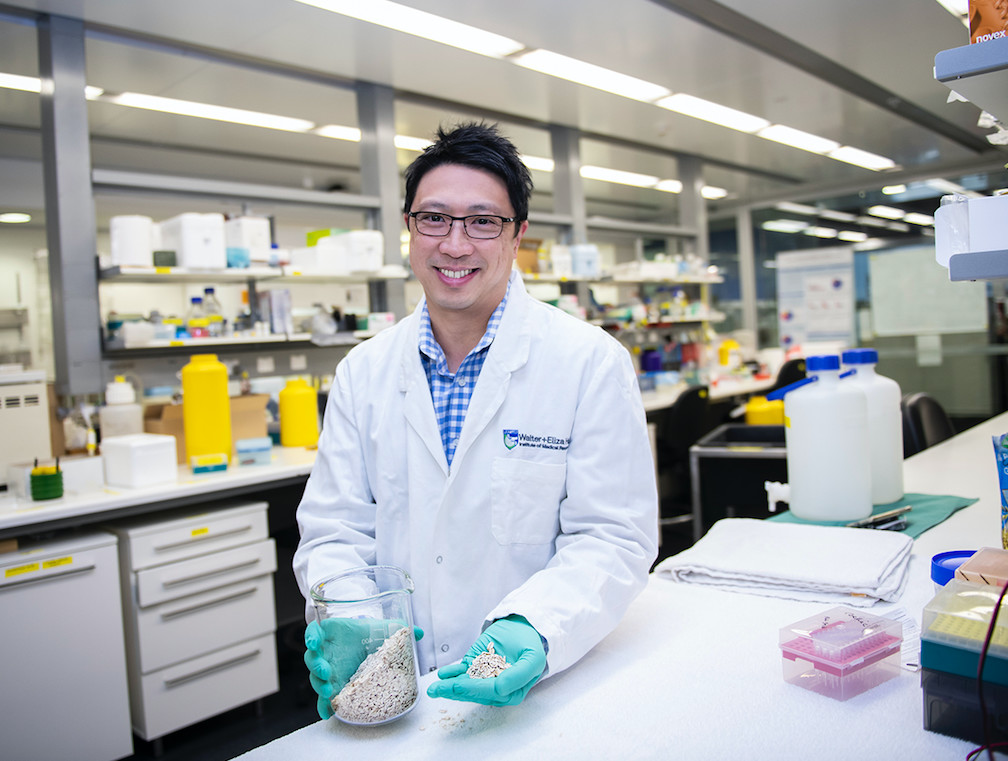

“I learned first-hand that adverse reactions to food can have a big impact on health and quality of life,” says Dr Tye-Din who is a Laboratory Head at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) and Mathison Centenary Fellow at the University of Melbourne.

“Food allergies weren’t common then, so its dangers were not appreciated and eating out was often risky.”

After growing up with this awareness of food, Dr Tye-Din decided to study medicine, specialising in gastroenterology in order to focus on the relationship between food, gut health and disease.

“As a gastroenterologist it was frustrating that all I could offer my coeliac disease patients was a lifelong and strict gluten-free diet. This was developed in the 1940s by Dutch paediatrician Wilhelm Dicke and I thought there had to be a better way,” Dr Tye-Din says.

Health & Medicine

Allergies, food labelling & saving lives

It is estimated that although 1.5 per cent of Australians are affected by coeliac disease, around 80 percent remain undetected and undiagnosed.

Coeliac patients have an immune intolerance to gluten – one of the major proteins in wheat, barley, rye and oats. If eaten, gluten triggers an abnormal immune response in the body that causes inflammation, similar to the body’s response in other autoimmune illnesses like type 1 diabetes. In both conditions, something the body should tolerate is treated as a threat.

For coeliac patients the response is so severe that the lining of the gut wall becomes inflamed and damaged, unable to absorb nutrients that the body needs.

Symptoms include abdominal pain, fatigue, bloating, diarrhoea and headaches, but complications as serious as lymphoma, osteoporosis and infertility can develop along the way.

The only treatment currently available to sufferers is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet.

In 2002, another gastroenterologist, Dr Robert (Bob) Anderson arrived in Melbourne from Oxford University and began his own research group at WEHI on coeliac disease.

“I became his first PhD student and my career in research and coeliac disease began,” says Dr Tye-Din.

Health & Medicine

How difficult decisions change our brains

“In 2000, Dr Anderson and colleagues published a paper in Nature Medicine that reported an entirely new approach to investigate immune responses to gluten in people with coeliac disease ,” says Dr Tye-Din.

“This work was ground-breaking as it was the first to use a patient’s blood to identify the main “toxic” fragment (peptide) from wheat gluten that triggers coeliac disease.”

The aim of Dr Tye-Din’s PhD research was ambitious – to define all of the toxic peptides in wheat, rye, barley and oats using the approach developed by Dr Anderson. The hope was to find the most important ones that could be used in a therapeutic vaccine to retrain a patient’s immune system to tolerate gluten.

Gluten is a visco-elastic protein that gives texture to foods and allows bread dough to rise and become fluffy. It’s a highly complex protein with each gluten-containing cereal carrying thousands of peptides. This complicates the puzzle, as only some of these peptides are likely to trigger the coeliac immune response.

So, for more than five years, scores of coeliac patients consumed wheat, rye, barley or oats and donated litres of blood between them for the purposes of research.

What the researchers wanted from their blood was immune cells known as CD4 T cells. These white blood cells begin the body’s immune response by releasing chemical messengers, alerting the immune system in response to an offending protein (in this case gluten).

Health & Medicine

Would graphic warnings on unhealthy food make you think again?

“We were able to test the T cell response from each coeliac patient to a massive library of peptides that encompassed all of gluten in each of the ‘forbidden’ cereals,” says Dr Tye-Din.

“This meant we could define the key peptides that stimulate the coeliac immune response from each cereal, and rank how important they were.”

And by 2010 they were able to publish their findings, revealing that just three key peptides, out of a possible 18,000 in all of the problematic grains, were responsible for the abnormal immune response to gluten in people with coeliac disease bearing the most common genetic marker.

The three gluten peptides were dubbed the ‘toxic trio’.

This ‘toxic trio’ formed the basis of a therapeutic vaccine that aims re-educate the body to develop tolerance to gluten, switching off the overactive response that occurs in coeliac disease.

Known as Nexvax2®, the vaccine has completed successfully the phase one of the safety trials and is now progressing to phase two, a major international trial to test its efficacy. It’s being developed by ImmusanT, a US biotech company that Dr Anderson is the Chief Scientific Officer for and Tye-Din is an advisor.

Health & Medicine

False labelling hides the truth about superfoods

The results to date are promising, says Dr Tye-Din, with the injections well tolerated, producing a biological signal that suggests it is modifying the immune response to gluten.

“However, the results of the current trial will have to wait till it is finished. As it is double-blind trial neither the participant or investigators don’t know who is receiving the real vaccine and who isn’t.”

Dr Tye-Din’s team are also developing new diagnostic tools for coeliac disease and investigating the genetic and environmental factors that may cause it to develop.

There is a lot of interest in how these factors modify the resident microbes in the bowel, known as the microbiome, and modify immune responses to gluten.

“Identifying the sequence of events that lead to coeliac disease may one day allow us to target at-risk children with strategies to prevent it developing in the first place.”

As the coeliac vaccine trials continue, the Tye-Din research lab works on improvements to the current treatment, the gluten-free diet.

“The gluten-free diet is not always successful, with only about half of patients restoring their gut lining and many suffering persistent symptoms.

“We want to know why, and we suspect that gluten-free food contamination may be an issue,” Dr Tye-Din says.

Sciences & Technology

More than just strong bones

“After analysing 127 food businesses in the City of Melbourne we found detectable gluten in 9 per cent of foods labelled ‘gluten free’. Over a third of these had very high and potentially harmful, levels of gluten.”

And Dr Tye-Din’s work has recently taken on a personal angle.

“Surprisingly, and very ironically, two years ago my wife was diagnosed with coeliac disease. So, as well as avoiding peanuts, the gluten-free diet is now a way of life for our family too.”

The hope is that one day it will be possible to restore normal gluten tolerance, but in the meantime a truly gluten-free diet remains the foundation for good health and quality of life for all coeliac patients.

Banner: Getty Images