Health & Medicine

Racing the clock against dementia

A simple blood test or scan could soon give a definitive all-clear for players struck in the head to return to the field

Published 9 December 2016

The football was bouncing along the wing during the last quarter of an amateur Australian Rules football match when 19-year-old medical student Terry O’Brien bent to scoop it up. But he didn’t see the opposition player hurtling towards him head-on. The collision would knock him out for several minutes and wipe all memory of the game after the first quarter.

“I remember feeling very confused and disorientated. I was so unwell I missed a full week of classes with headaches, dizziness, nausea and even some vomiting. It was a full month before I felt completely recovered,” he says.

It was near the end of the season and he didn’t play again for the rest of the year. Which was probably lucky. There is growing scientific evidence that the risk of permanent damage or a long-term degenerative brain disease from a concussion isn’t so much the number of concussions, but suffering another hit before the brain has had a chance to fully recover.

The problem is there is no definitive test of when someone has fully recovered from a concussion. Instead, clinicians have to rely on indirect and subjective measures such as monitoring cognitive ability, and symptoms like dizziness. But scientists are now on the way towards developing a simple blood test that may be able to give a definitive “all clear” on when a player can safely get back out on the pitch.

A team of researchers, led by Dr Sandy Shultz of the University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital, have identified potential physiological markers of concussion that they were able to successfully monitor in rats through blood analysis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The methodology is now being tested on humans, with 40 players from one of Australia’s oldest amateur Australian Rules football clubs, the Melbourne University Blacks, participating in a three-year study.

Health & Medicine

Racing the clock against dementia

For Professor O’Brien, the once 19-year medical student knocked out on the field all those years ago, it is a research project with huge community relevance. It could not only reassure professional athletes, but everyone playing sport at any level where concussion is a risk.

“Concussion is a transient brain injury that the brain recovers from, though the time it takes to recover varies with the person and the injury, ranging from just a few days to weeks or months,” says Professor O’Brien, of the University of Melbourne and the Royal Melbourne Hospital and part of the research team.

“But at the moment we don’t have a really good way of measuring that. So the point of the research is to develop a more sensitive and reliable method of determining when the brain has properly recovered from a concussion and people are safe to go back and risk another injury.”

The research, which also includes scientists from the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, the University of Newcastle and the Uniformed Services University in the US, has huge implications for improving safety in sports.

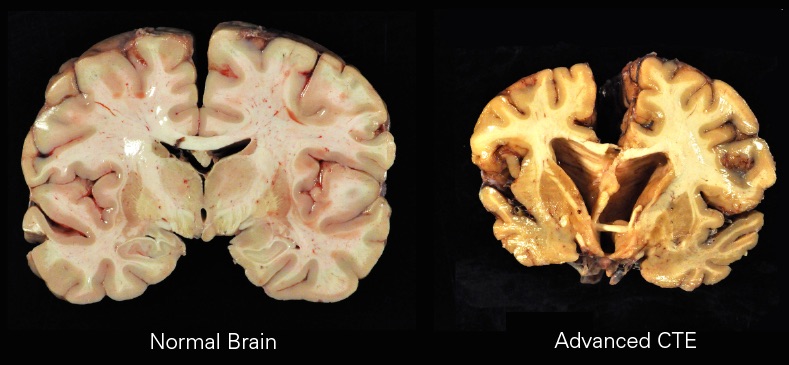

It comes at a time when there are growing concerns that retired players of sports where there is a high frequency of concussions are developing neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and motor neurone disease linked to concussion. In April a US Federal Court upheld a US$1 billion settlement between the National Football League (gridiron) and former players suffering certain neurological disorders.

The development of a blood or MRI test would also have wide application in the military given the risk of concussion from battlefield blasts, falls, vehicle crashes and flying debris. According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs, concussion is the “signature wound” of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The Melbourne reseachers’ study on rats, published in the journal Scientific Reports, has produced some of the strongest evidence yet that the current cognitive tests and symptom monitoring used to assess someone’s recovery from concussion aren’t reliable. Using MRI scanning and blood testing, the researchers found evidence of temporary brain abnormalities persisting as much as 30 days after a simulated concussion, when the cognitive testing had suggested the rats had recovered within five days.

The rats were delivered a mild concussion while under anaesthetic by injecting a “pulse” of fluid onto their brains and then the effects monitored using MRI scans, blood tests and cognitive testing. These cognitive tests involved assessing the ability of the animals to complete tasks such as navigating a maze and walking across a narrow beam.

“The most important thing we’ve found is that restoration of the cognitive deficit observed after concussion doesn’t indicate full recovery because we have picked up through the MRI and blood tests these other markers indicating that the brain was still in the process of recovering,” says imaging scientist Mr David Wright, the lead author of the paper and a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, based at the Florey Institute.

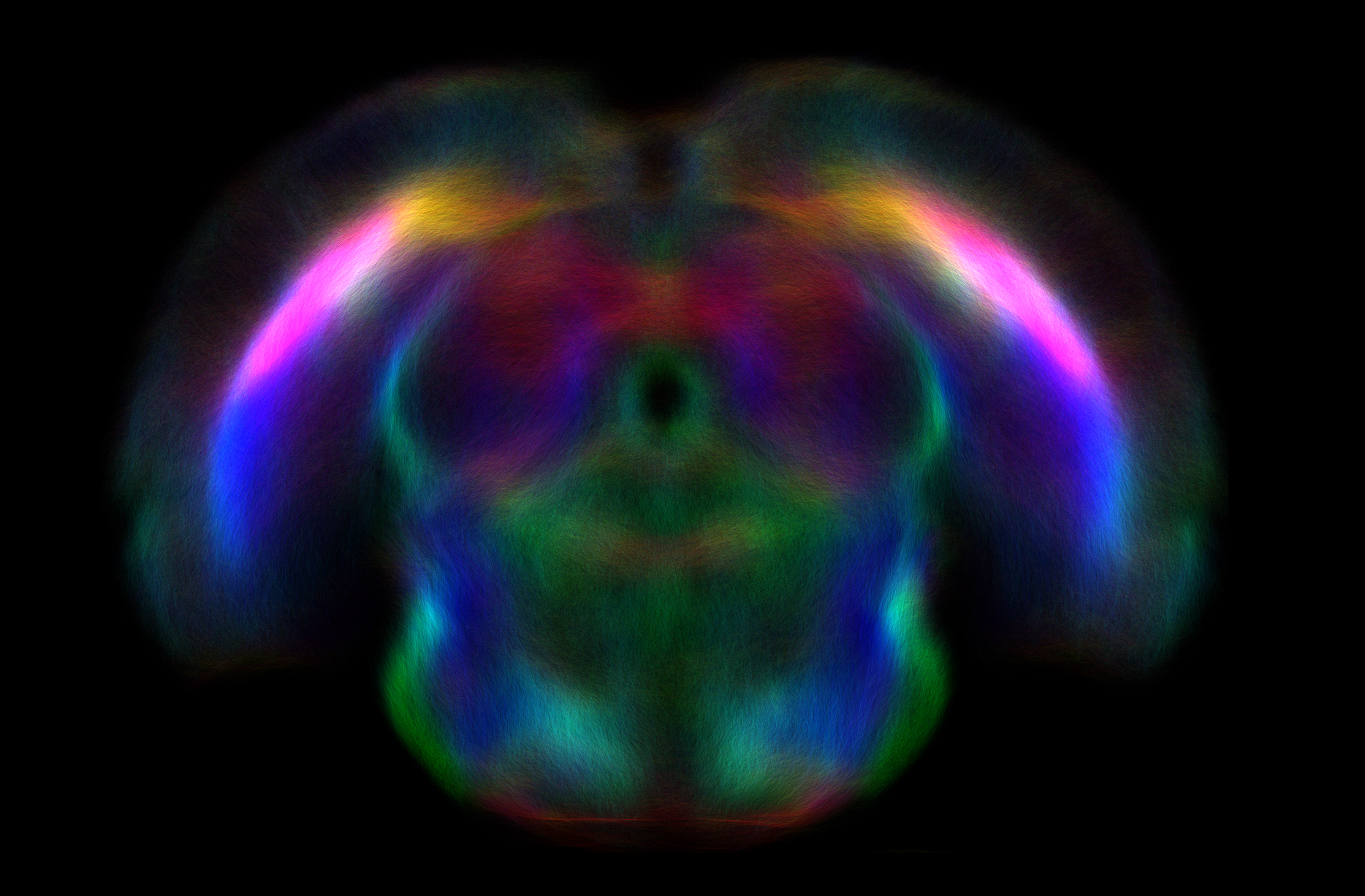

Using a special MRI technique that uses water molecules to enhance the imaging, the researchers were able to identify markers of concussion in the rats affecting the network of nerve cells in the brain known as white matter – in particular the cell projections that carry nerve impulses. These markers persisted well after cognitive testing had suggested the rats had fully recovered from their concussion.

Similarly blood tests were also effective in monitoring some markers of concussion such as temporary changes in levels of certain proteins inside nerve cells such as tau. Again in some cases these protein markers of impairment persisted well after cognitive tests had suggested the rats had recovered.

“The MRI and the blood tests are likely to be complementary, but the potential for developing a blood test is especially exciting because it can be so easily administered and the result analysed straight away,” says Mr Wright.

In an as yet unpublished study, the research team also found that when a rat suffered repeated concussions at a time when the biomarkers are indicating that the brain hadn’t yet fully recovered, the resulting impairment was worse and longer lasting.

“There is a theory this may be due to the repeated injury occurring while the brain is still in a period of increased vulnerability after the first (concussion),” Dr Shultz told the Herald Sun. “If that is the case it becomes very important not just to diagnose the initial injury, but also to determine who has recovered and is no longer in that period of increased vulnerability,” Dr Shultz said.

The human study has involved the Melbourne University Blacks players all undergoing cognitive, MRI and blood tests ahead of the season starting and then repeating the tests on players who suffer a concussion in order to monitor their recovery. In the last two seasons there have been eight cases of concussion and the study will enter its third year next season. According to the Australian Football League, rates of concussion across all levels of competition are about 6-7 injuries per team per season.

Former University Blacks club captain and now medical intern Dr Daniel Costello says the players have embraced the study, which has made them more aware of the dangers of concussion and the symptoms.

“Players increasingly self-report symptoms of concussion and voice their concerns about head knocks. The culture of downplaying symptoms to get back onto the field has definitely changed,” says Dr Costello, who participated in the 2015 study as a player and has acted as a research assistant on the study.

He retired from the game last year and throughout his playing time he was concussed three times, twice needing to be stretchered off the ground.

“Unfortunately there is uncertainty around the best way to manage concussions and so a conservative approach is safest. Currently, concussion diagnosis and management is largely based on symptom checklists, which can be subtle and difficult to interpret. We need to take some of the guesswork out of concussion management. Objective biomarkers could provide the solution and help guide return-to-play timeframes,” Dr Costello says.

The research team is also investigating whether a drug being tested as a treatment of Alzheimer’s, sodium selenate, could help people recover from concussion and even damp the effects of a concussion if taken as a precaution. Test results on rats published in the journal Neuropharmacology indicate that the drug does reduce brain damage and cognitive impairment resulting from concussion. The drug acts to control levels of a toxic form of the tau protein that is associated with both long-term degenerative brain diseases and temporary impairment from concussion.

“What we have realised is that tau is important in the whole brain injury story,” says Professor O’Brien. “So the idea is that we might be able to use this drug not only as a treatment or concussion but also as a way to fortify the brain to reduce the impact of a potential concussion.”

Banner Image: Shutterstock