Politics & Society

What’s next for the Republicans after Trump?

Turkey’s opposition parties are mobilising against increased authoritarianism by using the Government’s own laws to establish new alliances

Published 17 November 2020

Turkey’s steady transformation from a democracy to an authoritarian regime has been radical.

While ostensibly still democratic, Turkey is now what political scientists call a “competitive authoritarian” system where the government has a largely free hand to abuse the democratic apparatus.

Prime minister-turned-President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan now wields personalised power over the government and critical state institutions, dramatically shrinking the scope available to opposition parties.

When we look back at the past activity of opposition parties in Turkey, it has been their pronounced fragmentation and inability to bridge their differences that has been a key reason for enabling Erdoğan to strengthen his rule and squeeze the space for them to operate.

But this is now changing.

Politics & Society

What’s next for the Republicans after Trump?

The opposition parties are increasingly cooperating to deny Erdoğan and his Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (Justice and Development Party, AKP) political hegemony and instead maintain political pluralism. And paradoxically they are using one of Erdoğan’s own laws against him.

In March 2018, the AKP government passed a new ‘electoral alliance’ law permitting alliances between parties.

The legislative change was aimed a protecting Erdoğan’s government after he was spooked by the narrow 51.4 per cent win he had secured in the 2017 constitutional referendum that increased his presidential powers.

The result suggested victory in the upcoming 2018 election was far from assured. The new legislation meant he could formalise a pre-existing partnership with the Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (Nationalist Action Party, MHP).

The alliance would prove crucial after the AKP secured only a 43 per cent parliamentary vote in the election, meaning it has to rely on the MHP’s 11 per cent share to govern under the Cumhur Ittifakı (People’s Alliance) banner.

But the law also facilitated unprecedented cooperation among Turkey’s ideologically dispersed opposition parties.

Ahead of the 2018 election, the opposition formed the Millet Ittifakı (Nation Alliance) made up by the secular centre-left Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (Republican People’s Party, CHP), centre-right nationalist IYI Parti (Good Party), the Islamist Saadet Partisi (Felicity Party, SP), and the centre-right Demokrat Partisi (Democrat Party, DP).

As CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu said in an interview ahead of the election:

Politics & Society

The limits of government outsourcing

“We, as different political parties, are coming together as a show of democratic strength and unity. This is a first in Turkey. As diverse political parties we have come together to strengthen democracy, to strengthen human rights, to solve outstanding problems through a democratic parliamentary system. This is very important to us.”

The opposition solidified this new alliance by signing a pro-democratic declaration pledging to “end polarisation, instill independence of the judiciary and the rule of law, and ensure basic rights and freedoms”.

Moreover, one of the primary aims was to re-instate a strengthened parliamentary system.

Under the alliance, the individual parties still selected their own candidates for the presidential race. The CHP nominated Muharrem Ince, an internally popular, charismatic politician with a national profile as its presidential candidate, whilst IYI and SP nominated their respective leaders, Meral Akşener and Temel Karamollaoğlu.

All three candidates campaigned independently, but they ultimately worked off the same platform as the Nation Alliance’s democratic pledge.

A critical component of their cooperation against Erdoğan included refraining from criticising each other, and all three candidates pledged to endorse each other in a potential runoff and serve as vice-presidents in a future cabinet.

Throughout the campaign the opposition ran a highly effective and innovative strategy against the unequal conditions and constricted political space in which it had to operate.

Politics & Society

Principles aren’t enough when human rights meet business

Ince, Akşener, Karamollaoğlu and CHP party leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, as key symbols of the alliance, appeared regularly on the few independent media outlets – Fox Türk, Halk TV, Deutsche Well Türkçe and Haber Türk – and each ran a tireless campaign schedule across the country.

For instance, İnce organised 107 rallies in 75 cities and Akşener visited 81 cities from the time she established IYI in late 2018.

Most of the rallies and speeches were broadcast live on social media platforms, allowing the alliance to reach audiences and work around the monopoly of the media landscape that Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance enjoy.

This successful campaigning by the opposition occurred in spite of the imbalances skewed towards the AKP and Erdoğan.

The People’s Alliance financed their campaign with presidential and state funds as well as making sure the opposition received near to zero television time on Turkish TV channels owing to the AKP’s monopoly of the media landscape.

Given the fraught relations between the Turkish state and its minority Kurdish population, the pro-Kurdish rights Halkların Demokratik Partisi (Peoples’ Democratic Party HDP), wasn’t part of the opposition alliance and, instead, contested the parliamentary elections independently.

They listed their imprisoned former co-leader Selahattin Demirtaş as its presidential nominee.

But the opposition Nation Alliance’s need to increase their electoral reach and present a legitimate democratic platform incentivised the member parties and candidates to move beyond their traditional political identities and appeal to the Kurdish electorate.

This strategy also offset the AKP’s attacks on the Kurdish movement, and the very nationalist polemic it had employed throughout the campaign.

Arts & Culture

How Arabic is a window on the world

Ince’s presidential campaign embodied this outreach strategy the most. He broke with the CHP’s dominant nationalistic character and visited Selahattin Demirtaş in prison.

He also held lively campaigns in Kurdish-majority cities, often attracting large crowds where his speeches were characterised by democratic inclusivity.

Moreover, Ince promised to implement a long-time demand of the pro-Kurdish movement – to devolve administrative powers to elected local officials in line with the European Charter of Local Self-Government.

Outreach by the opposition helped loosen traditionally entrenched suspicions against the CHP (which was long considered a haven for anti-Kurdish sentiment by citizens in the south east of Turkey).

Similarly, Akşener, from the IYI Parti, attempted to reach out to Kurds through her democratic platform and meetings in Kurdish majority areas. Her nationalist credentials and former role as Interior Minister in the 1990’s (a rather dark period in Turkish-Kurdish relations) was her weakness for the Kurdish vote-base.

Akşener’s centre-right nationalist position limited her appeal and success with Kurdish voters, but her campaign strategy demonstrated political actors can pragmatically overlook ideological constraints in order to more effectively challenge existing regimes.

In the wake of this new cooperative approach among the opposition parties, the AKP actually lost its majority, and only maintained its parliamentary control due to its alliance with the MHP.

Politics & Society

The state of democracy, before and during COVID-19

The election outcome demonstrated that despite the fast-shrinking political space and limited openings for the opposition, they were able to adapt to Erdoğan’s authoritarian regime and remain in the contest.

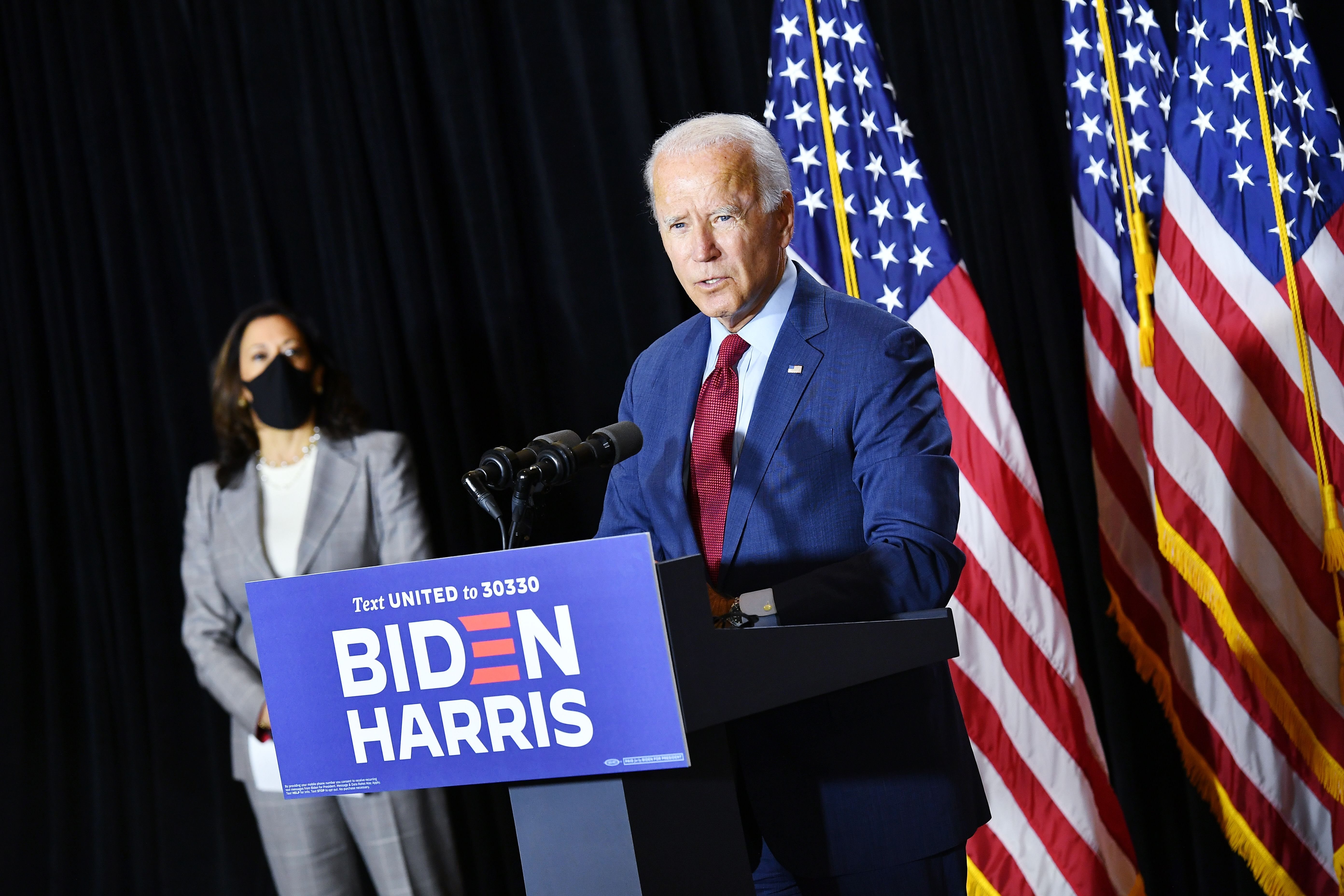

With incoming US president Joe Biden, Erdoğan will see a sharp rise in criticism from Washington compared to the Trump administration.

In previous interviews, Biden has labelled Erdoğan a “tyrant”, expressing his wish to support the Turkish opposition to remove Erdogan through the ballot box.

Although Turkey’s opposition is extremely unlikely to work with the Biden administration against Erdoğan, they will quietly welcome any sharp criticism and pressure from the Biden White House in the hope it will force Erdoğan to take democratising steps, bringing greater opportunities of contention and contestation.

This article was co-published with Melbourne Asia Review, Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne.

Banner: Getty Images