Politics & Society

Like Canada, Australia has rejected Trump’s disruption

Focusing on the ‘Trump-lite’ policies of the Liberal Party obscures the deep structural issues it faces

Published 7 May 2025

On Saturday 3 May, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese defied even the most optimistic projections and secured an historic electoral victory for the left-leaning Labor party.

To put the scale of Labor’s victory into context: Albanese is the first Labor Prime Minister since Bob Hawke in 1984 to win a second term in office.

At the time of writing, Labor has secured a two-party preferred (TPP) vote of 54.9 percent compared to the Coalition at 45.1 percent. This is Labor’s highest TPP vote since John Curtin in 1943.

Only three other leaders have taken Labor from opposition into government since World War Two: Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Kevin Rudd. Albanese’s 2025 re-election victory eclipses them all.

No wonder that Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers described Albanese as a “Labor hero” on election night. In pure mathematical terms, he is.

Albanese often claims that he has been underestimated his whole life. Given that Labor was predicted to fall into minority government at best just three months ago, even Albanese’s most stubborn critics have to admit that he has a point.

Still, being underestimated hardly explains the nature and scale of Labor’s victory. To what does Anthony Albanese owe his newfound place in Australian political history?

Politics & Society

Like Canada, Australia has rejected Trump’s disruption

Firstly, even Coalition MPs admit that Labor ran an incredibly effective, disciplined and professional campaign. Labor successfully reframed the election contest, turning it from a referendum on the last three years – during which time Australian voters suffered under high interest rates and inflation – into a choice about the next three years.

Central to this strategy was Medicare. Medicare (think Australia’s version of the National Health Service in the UK providing universal healthcare) was created by Bob Hawke in 1984.

Whenever Labor senses trouble in the polls, they announce some measure to strengthen or expand Medicare.

By promising that 90 percent of doctor’s visits would be free by 2030, Albanese was able to reframe Medicare into a cost of living issue. This paid electoral dividends because cost of living was consistently ranked as the number one priority for voters.

But Medicare always features heavily in Labor’s election campaigns. Clearly, something else is going on.

Without wanting to detract from Albanese’s preternatural political judgement, Labor’s campaign was undeniably helped by the unpopularity of Opposition leader Peter Dutton.

According to internal research done by Coalition pollster Michael Turner, Dutton’s approval rating was at negative 40 percent by election day.

These polls proved correct. Dutton became the first Opposition leader in Australian history to lose his seat at a federal election.

It would be tempting to lay the blame for the scale of the Coalition’s loss on Peter Dutton’s uniquely unpopular political style. Indeed, he was widely criticised for adopting ‘Trump-lite’ policies that ultimately alienated voters, like cutting the public service and criticising “wokeness” in schools.

However, focusing on Dutton’s personality obscures the deep structural issues facing the Liberal Party. In many respects, the 2025 election results were a long time coming.

Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

Arguably, the problem began when Tony Abbott became leader of the Liberal Party (and thus leader of the Coalition) in 2009, beating Malcolm Turnbull by just one vote. Abbott immediately shifted the party further to the political right.

Under Abbott’s leadership, the Coalition voted against the then-Labor government’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS).

When the Coalition swept to power in 2013, Abbott appointed just one woman to federal cabinet. He appointed himself as Minister for Women.

Fast forward to 2022, and the Coalition’s own election review blamed the party’s loss on the “perceptions” that they were not responsive to the concerns of women or alert to the dangers of climate change.

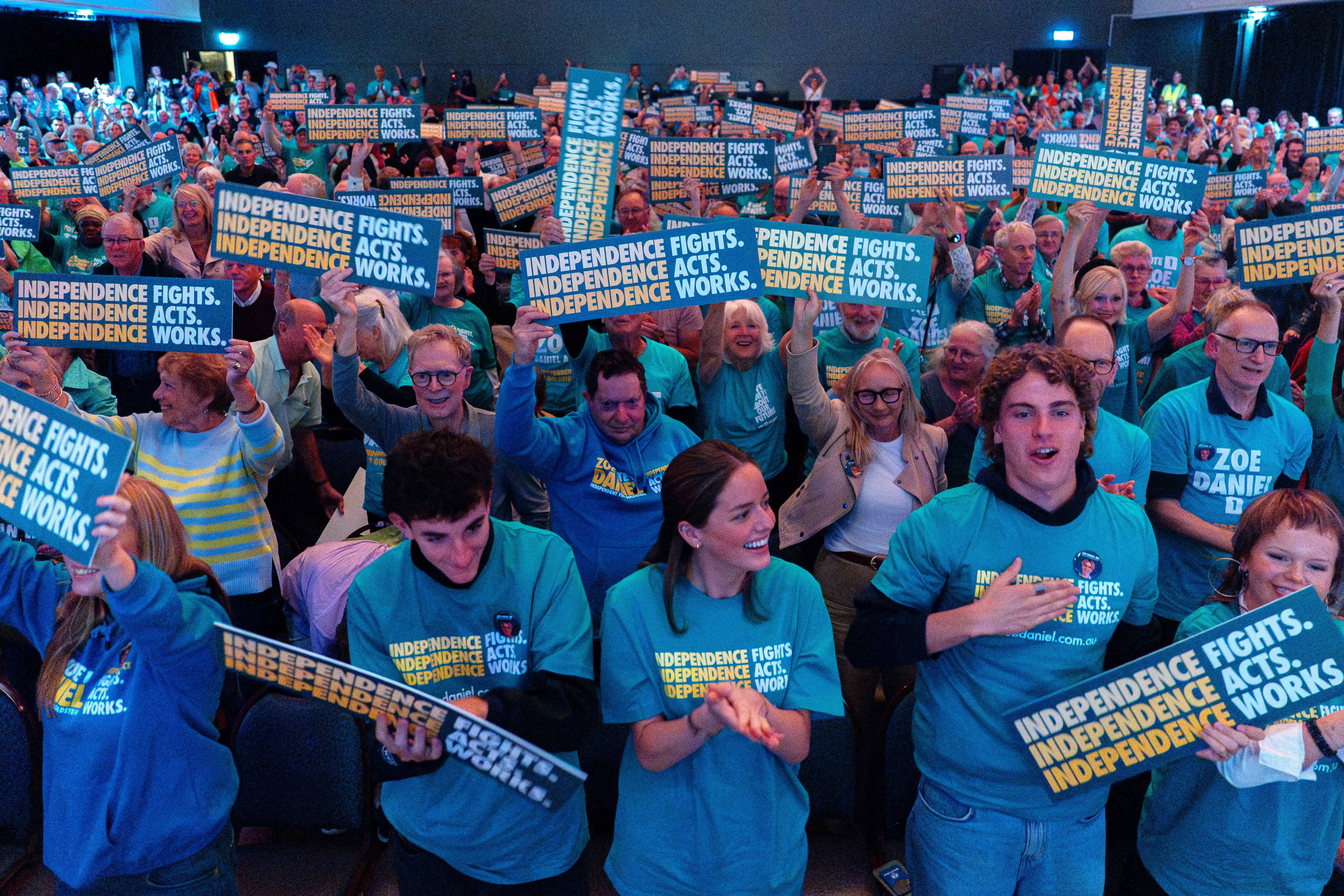

As a result, they lost six formerly safe seats to so-called ‘Teal Independents’– all of whom were women and in favour of acting on climate change.

By 2025, it would seem that the Coalition had failed to take these lessons to heart.

On the climate front, they spent the last three years attacking Labor’s rollout of renewable energy. When it comes to a better understanding of women’s issues, Peter Dutton notoriously claimed that if female public servants did not want to return to the office full-time, they could always job-share.

In other words: take a pay cut.

In response to their comprehensive loss at the polls, several Coalition figures are already urging the party to become more attractive to women and young people, as well as to act on climate change by embracing renewable energy.

These remarks raise the obvious question: why weren’t these lessons learnt three years ago? Because, to put it quite simply, there are not enough Coalition MPs left inside the party who are willing to listen.

Politics & Society

The subtle theatre of Australia’s election season

Once a majority of moderate MPs lose their seats, there are not enough people left inside the party who can steer it in a more centrist direction. A vicious cycle then takes hold: moderates lose their seats, the party becomes more conservative, resulting in more moderates losing their seats.

The Coalition is caught in a downward spiral.

Because the internal ideological complexion of the party has changed so dramatically, those remaining in parliament are more inclined to listen to conservative commentators like Peta Credlin, who suggested on election night that the Coalition “didn’t do enough of a culture war”.

Similarly, Australia’s richest person and a major donor to the Coalition, Gina Rinehart, has urged the Coalition to stick with “Trump-like” policies, and blamed the media for Dutton’s loss.

After Saturday’s election result, the number of Coalition MPs who are inclined to agree with this analysis has increased as a proportion of the overall party room.

Unless the Coalition can learn the lessons of the 2022 and 2025 elections, its electoral woes will get worse before they get better. A time of soul-searching and bitter infighting awaits the party.

Dutton was praised for keeping the Coalition united after their 2022 loss. But by avoiding uncomfortable conversations about where the party went wrong, the Coalition failed to course-correct.

Perhaps Dutton’s greatest strength as leader was also, in the end, his greatest weakness.