The Battle of Kursk: 75 years on

The human and material toll of the world’s largest tank battle was horrendous as the Wehrmacht’s tactical edge was overwhelmed by superior means of destruction

Published 13 July 2018

In July 1943, during a moment of respite amid the heavy fighting going on all around him, Soviet tank man Lev Nikolaevich Malinovskii wrote from the Kursk battlefield to his brother: “The fighting today lasted five hours. Together with our artillery we burned and destroyed twenty-one German tanks.”

Dinner was brought up to the line, but he was too exhausted to eat. July can be hot in Russia. In 1943 it was forty degrees centigrade. The crews in the Soviet T-34s sweat through their uniforms. “My tunic was soaked,” wrote Malinovskii.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Kursk (5-16 July 1943). Its climax, the Battle of Prokhorovka (12 July), is routinely described as “one of the largest tank battles in military history.”

Historians once viewed the battle as a turning point – a Soviet victory which ended the Wehrmacht’s ability to wage offensive war in the East. Recent research is more circumspect, stressing the surprisingly good performance of the Germans but also the overall strategic advantage of the Soviets, which nullified such tactical superiority.

A battle of economics

As David Stahel of UNSW at the Australian Defence Force Academy, a leading operational historian of the Wehrmacht in the East, put it in an interview a few years ago: “Ultimately, whether a hundred extra German tanks went this way or that, does that really determine the outcome of the battle? I think not.”

More important were overall economic factors, in particular the ability of both sides to produce the means of destruction, to field men and war machines in large quantities.

Here, the Soviets were far superior to the Germans.

Nevertheless, Kursk became a major moment in the official Soviet war narrative, which took the Red Army from Moscow to Stalingrad, then on to Kursk and eventually to Berlin.

It was such an iconic part of the mythology of this war, that even those who had not fought there aimed to write themselves into its history.

“Our 3rd airborne brigade,” wrote the later film director, Grigorii Chukhrai, “was transferred to Belarus, to the city of Slutsk. Through the windows of our rail cars we saw the traces of a grandiose battle.

“The gun barrels of gutted tanks protruded from the marshes. Burned out turrets and spilled tracks were everywhere. A lot of corpses, too. Our train passed the site of the recent battle of Kursk.” After this introduction, Chukhrai goes on to spend four pages of his memoirs describing a battle he had not seen himself.

Politics & Society

Is the Russian Revolution over yet?

The battle itself was horrendous. Anticipating the German attack, the Soviets fortified themselves in a complex set of trenches and minefields. Large numbers of anti-tank guns were strategically positioned to shoot the German Panzer (tanks) to pieces.

Longer-range artillery covered the approaches. Infantry lay in hiding, nervously smoking and downing their “frontline 100 grams” of vodka in anticipation of what was to come. Soviet T-34 tanks stood concealed, ready to lead the counter-strike.

The trap was set.

Human cost

On 5 July, after many delays, the Germans finally attacked – 2,730 Panzer advanced, including the fearsome new Panther and Tiger tanks.

They were supported by just under a million men and 10,000 pieces of artillery, creating an inferno of shrieking metal, howling motors, thundering explosions and the cries of wounded men. Aircraft pelted the Soviet defenders with bombs and machine-gun fire. Despite nearly a fortnight of fierce fighting, however, no breakthrough was achieved.

The final tally of the battle was gruesome. Some 70,000 Red Army and 57,000 Wehrmacht soldiers were dead or wounded, while 1,600 Soviet and 300 German tanks were destroyed.

This discrepancy is all the more striking if we remember that attacking forces tend to take greater losses than entrenched defenders. Clearly, the Wehrmacht was still the superior fighting force.

Health & Medicine

War and trauma: Learning the lessons

This tactical superiority, however, couldn’t be exploited in the war of attrition the Germans faced. The Panzers didn’t manage to break through the staggered Soviet defences.

Eventually Hitler withdrew his forces to save what was left of his tanks. As the Führer’s soldiers moved back, they were attacked by the Red Army throughout the rest of the summer of 1943.

No chance

An immensely bloody but inconclusive local engagement turned into a strategic defeat of the invaders. From then on, the Germans fought a bitter and costly retreat and the Red Army soon advanced into what Soviet propaganda called the “lair of the fascist beast.” In the spring of 1945 Stalin’s soldiers would take Berlin and end the Second World War in Europe.

The Soviets won because of their vast superiority of human and material resources. During the battle of Kursk, the Red Army had thrown in twice as many men, guns and machines than the Germans.

This crushing superiority was made possible by the immense capability of the Soviet economy to churn out standardised tanks, guns, and other equipment, and the capacity of the Soviet state to mobilise the huge human resources of the largest country in the world. Both of these abilities were the result of the Stalinist mobilisation and industrialisation drive of the 1930s.

The military potential of the Soviet warfare state was further enhanced by its alliance with the largest economy on earth; the United States sent food supplies, tools, two-way radios and trucks – supplies which closed crucial gaps in Soviet production.

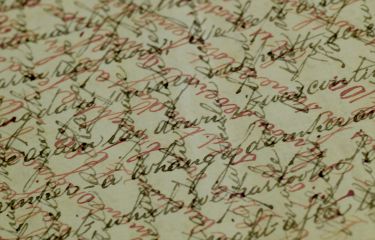

Arts & Culture

Criss-cross history hidden in a letter

Faced with such an enemy, the Germans had always been delusional in their hope to conquer Stalin’s empire quickly and efficiently.

Most historians today argue that Hitler’s army never had a chance.

However, it took over three and a half years of fearsome fighting, unbelievable suffering and unprecedented destruction to prove this point.

Tank man Lev Nikolaevich would never know the outcome. Like 7.8 million other Soviet soldiers he didn’t live to see victory. He was killed on 15 December 1943 in an artillery barrage in Belarus.

Banner Image: Russian schoolchildren bring portraits of their relatives who fought in the 1941-1945 Great Patriotic War, the Eastern Front of World War II, for a memorial event on 5 May, 2017 marking the 72nd anniversary of the victory over Nazi Germany. Vladimir Smirnov/TASS/Getty Images