Health & Medicine

Targeting ovarian cancer

A new blood test for cancer patients identifies microscopic cancer DNA in the blood stream – which can tell us whether chemotherapy is necessary or not

Published 17 October 2018

A diagnosis of cancer can be terrifying – but sometimes the treatments themselves can be just as frightening for patients.

Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy – it can be incredibly daunting and some of the side effects from these life-saving technologies can be life changing.

Chemotherapy is still the mainstay of most cancer treatment and has saved countless lives – but our research is working toward identifying when chemotherapy may not be necessary.

Our research team has developed a new blood test that aims to assess a patient, after cancer surgery, to determine whether they need chemotherapy or not; finding and measuring cancer DNA in patient’s blood could revolutionise cancer care.

The blood test is currently in clinical trials at more than 40 hospitals in Australia and New Zealand - making it one of the largest trials both in Australia and around the world that’s investigating a predictive blood test to guide cancer treatment.

Health & Medicine

Targeting ovarian cancer

We have been specifically investigating bowel cancer. At the time of diagnosis, many early stage bowel cancer patients have tumours that appear to be limited to the bowel, with no evidence of spread to elsewhere in the body.

But, following successful surgery to remove the cancer, around a third of these patients will get a recurrence elsewhere in the body in the following years – this means the cancer cells had already spread at the time of diagnosis, but couldn’t be detected using our current standard blood tests and scans.

If these patients had been treated with chemotherapy after surgery, about a third of relapses would have been prevented by eradicating the microscopic residual cancer cells responsible for the cancer’s return.

Currently, the decision to use chemotherapy is based on pathological assessment of the bowel cancer removed at the time of surgery.

For example, the discovery of cancer cells in the lymph glands next to the bowel (known as a Stage III cancer) means there is an increased probability that the cancer has already spread.

But while pathology information is useful, it lacks precision. Some high-risk patients won’t have cancer recurrence because their cancer has been cured by surgery alone, while other apparently low-risk patients will suffer recurrence.

This lack of ability to accurately determine who has microscopic disease and is most at risk of relapse means that many patients are currently treated with six months of chemotherapy.

This means dealing with the sometimes tough side effects of chemotherapy, even though they may not need to have the treatment. Meanwhile, other patients that would potentially benefit don’t receive the necessary chemotherapy, because they appear to be at low risk.

Health & Medicine

Filling in the genetic blanks of breast cancer predisposition

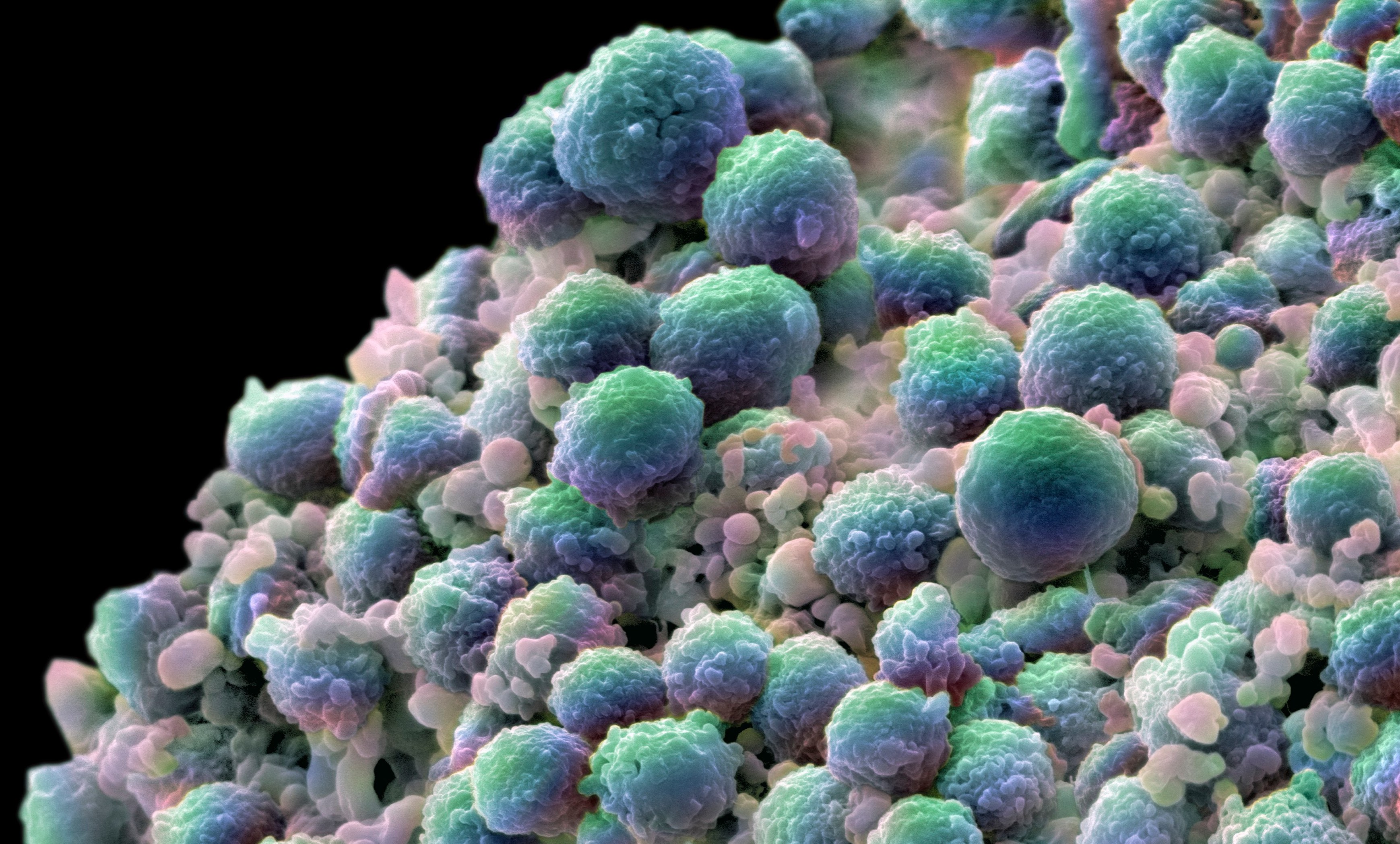

When cancer cells rupture and die, which is constantly happening in all cancers, they release their contents, including cancer-specific DNA that floats freely in the bloodstream – this is called ‘circulating tumour DNA’.

The detection of ‘circulating tumour DNA’ after bowel cancer surgery indicates there’s remaining microscopic cancer cells in the patient that couldn’t be picked up by standard tests.

Our new ‘circulating tumour DNA’ blood test has been developed through a collaboration between the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Centre in the US.

This research shows that patients who test positive for ‘circulating tumour DNA’ after surgery have an extremely high risk of cancer relapse - close to 100 per cent. While those with a negative test have a very low risk of the cancer returning - less than 10 per cent.

The next step is to show that using this blood test can personalise chemotherapy; avoiding unnecessary chemotherapy in those people with low-risk cancer as well as improving cancer survival in those with very high-risk disease by intensifying their treatment.

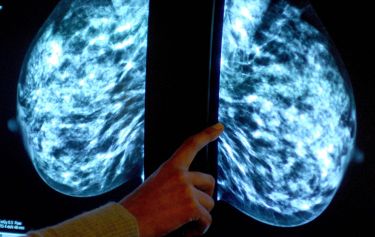

The trials began in early stage bowel cancer patients in 2015 and have already shown the blood test can determine whether these patients can be divided into ‘high risk’ and ‘low risk’ groups. In 2017, the trial was extended to include women with ovarian cancer – and we soon hope to include pancreas cancer.

More than 400 patients have already joined in the trials of the ctDNA test but we hope to recruit more than 2000 participants. Currently 40 hospitals across all states in Australia and in New Zealand are taking part, which is expected to run until 2021 for bowel cancer and 2019 for ovarian cancer.

But crucially, this blood test could become yet another tool in our kit to help diagnose and treat cancer, and ultimately, save lives.

The trials are funded by the Marcus Foundation (US), the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council, the Victorian Cancer Agency and Victorian Government. The bowel cancer and pancreas cancer trials are endorsed by The Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG).

If you’re interested in the trials - you can get more information on the trials for Stage II colon cancer, Stage III colon cancer, Rectal cancer, Pancreatic cancer and Ovarian cancer.

Banner image: Wellcome Collection