Health & Medicine

It’s a fact: Women get better with age

The history of women’s health in Victoria and the establishment of the Royal Women’s Hospital, has been traced through unprecedented access to archival collections

Published 23 July 2019

‘The colony was in the midst of a gold rush that would bring half a million people in the decade. Women were abandoned – pregnant and destitute – while their husbands and erstwhile lovers tried their luck on the goldfields. The need for a charity lying-in hospital for women without homes was urgent.’ – Professor Janet McCalman AC (BA 1971), Historian.

The Victorian gold rush, in the mid-nineteenth century, represented a period of immense wealth and population growth that helped establish Melbourne as one of the richest and most thriving settlements in the colonies.

The surge of population brought social and economic upheaval and it was an era that vilified women who, through no fault of their own, fell afoul of contemporary social mores.

Health & Medicine

It’s a fact: Women get better with age

Women on the periphery of society – in poverty, widowed or deserted by partners, or pregnant out of wedlock – were all but excluded from access to adequate health services. The number of infants and women dying in childbirth climbed and the need for providing health care to women became imperative.

A committee of women, led by Mrs Frances Perry and two male doctors, Dr Richard Tracy and Dr John Maund, set to work to establish a facility that would provide universal health care and treatment for women.

In August 1856, the Melbourne Lying-In Hospital and Infirmary for the Diseases Peculiar to Women and Children opened in an East Melbourne terrace house. Since its establishment, the hospital, now in Parkville, has remained committed to the underprivileged.

The University of Melbourne’s Medical History Museum and The Royal Women’s Hospital’s History, Archives and Alumni Committee have produced a major exhibition to showcase the hospital’s important role in healthcare.

The Women’s: Carers, advocates and reformers exhibition and accompanying catalogue trace the history of women’s health in Victoria, and particularly at the Royal Women’s Hospital.

Health & Medicine

How good cholesterol can keep women’s brains healthy

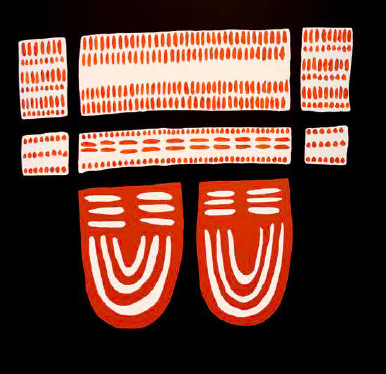

Importantly, the rich history of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and practices for pregnancy and childbirth is also acknowledged through contributions by senior Victorian Indigenous women.

Among the Medical History Museum’s collections is the first Annual Report of the Melbourne Lying-In Hospital and Infirmary for Diseases of Women and Children.

Dated 13 December 1856, it states that one of the hospital’s distinguishing characteristics would be ‘the admission … of poor women during their confinements, with provision to ensure proper medical attendance, with judicious and kind nursing during their stay’.

From its beginnings in 1862, Melbourne Medical School has had strong connections with the hospital. One of the hospital’s founders, Dr Richard Tracy, was the University’s first lecturer in obstetric medicine and diseases of women and children.

The exhibition includes his ovariotomy instruments that were sent to Dr Tracy from England by his mentor, Sir Thomas Spencer Wells, who was surgeon to Queen Victoria and a leader in obstetrics.

Health & Medicine

Busting five myths about pregnancy

Richard Walpole, a descendant of Dr Tracy and contributor to the exhibition catalogue, writes that: “Tracy performed the first successful ovariotomy in Victoria in 1864, and became renowned locally and internationally for a series of successful ovariotomies”.

Walpole explains that it was solely through written correspondence with Wells that Tracy was instructed in his pioneering technique to remove ovarian tumours.

Also on show is a midwifery nurse’s case that belonged to Florence Green. She trained as a midwifery nurse at the Women’s in a two-year scheme designed for women without prior qualifications in nursing.

Those enrolled in midwifery training received certificates bearing the title ‘Obstetrical Nurse’, a term adopted in 1898 to replace ‘Ladies Monthly Nurse’.

“As was required, Green’s case is lined with a draw-sheet. Starched white aprons, collar, cuffs and studs, cloth belts with silver buckles, cap, silk stockings, and a silk handkerchief seem ready for the next wearing,” writes University of Melbourne Historian, Dr Madonna Grehan.

“A large enamel dish holds a nail brush, gallipots for solutions, and a kidney dish for injections. Other items include a glass urinary catheter and pipettes, enemata, a measuring glass for medications, syringes and needles, bottles, bandages, cotton swabs and gauzes.

“There are artery and other forceps, scissors, twine to tie the umbilical cord, safety pins, and a metal spoon for measuring baby formula.”

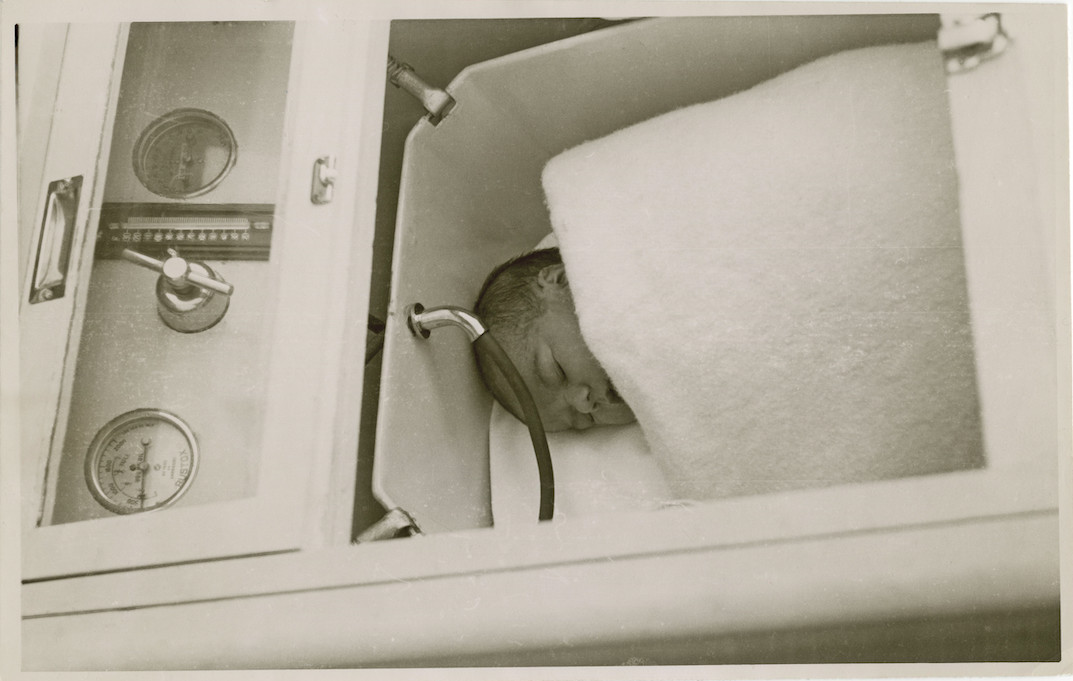

Rapid advancements in medical science during the mid-twentieth century are highlighted by an incubator, constructed in 1949 by Women’s chief engineer, Mr Jack Murphy.

It was used to transport newborn infants within the hospital and was suspended on springs and warmed by hot water bottles. Oxygen from an externally placed cylinder passed through the incubator walls to be warmed before consumption by the infant.

The exhibition details changing focuses in women’s nutrition, contraception, substance abuse and mental health.

The hospital’s long history of treating gynaecological conditions, abortion and childbirth complications are chronicled, including the often-tragic consequences of backyard abortions before the procedure was legalised.

The health needs of women on the fringes of society remain a priority for the hospital and the exhibition and catalogue detail this continued commitment.

“Today it is the homeless, those with substance abuse issues, those from the lowest socioeconomic groups, refugees and others,” says Associate Professor Les Reti, head of gynaecology at The Women’s.

The Women’s: Carers, advocates and reformers provides unprecedented access to collections that navigate the history of women’s health in Victoria and explores the figures, technology and social challenges that illustrate the historical, scientific and social impact of The Women’s Hospital in Melbourne. The exhibition runs until 2nd November, 2019 at The Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne, Monday to Saturday.

Banner: Three pupil nurses and babies, 1956, photograph, Royal Women’s Hospital Collection.