The case for an Australian Climate Accord

Australia lacks national leadership on climate policy, but an Australian Climate Accord could foster agreement on reducing emissions while improving Australia’s living standards

Published 27 October 2021

The 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report indicated the world is likely to reach 1.5°C of warming within nine, short years.

This shrieking emergency siren quickly disappeared from the front page of Australia’s popular media, matching the approach by the Federal Government to stall making firm commitments on climate change. Avoidance of a coherent climate policy is representative of the deep climate divisions within the coalition.

Our national climate change actions and targets recently saw us ranked last out of 200 countries.

In early November, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change will host COP26 to negotiate a path forward to limit warming of global surface temperature to 2°C , preferably 1.5°C.

In 2015, Australia committed to a 26 to 28 per cent reduction in emissions by 2030, from a baseline of 2005 levels. While other countries have progressively increased their emission reduction targets, Australia’s target remains unchanged.

Given Australia is the driest inhabited continent, we are highly exposed to climate change impacts, including drought, bushfires and cyclones. It’s in our national interest to avoid potential future warming.

But current national commitments to reduce emissions, if replicated across all countries, aren’t enough to limit global warming to 1.5°C, or even 2°C. As a wealthy economy with clear capacity to generate renewable energy, other countries expect Australia to take the lead in reducing emissions.

Meeting our current target

Furthermore, Australia isn’t on track to meet even its modest reduction commitment.

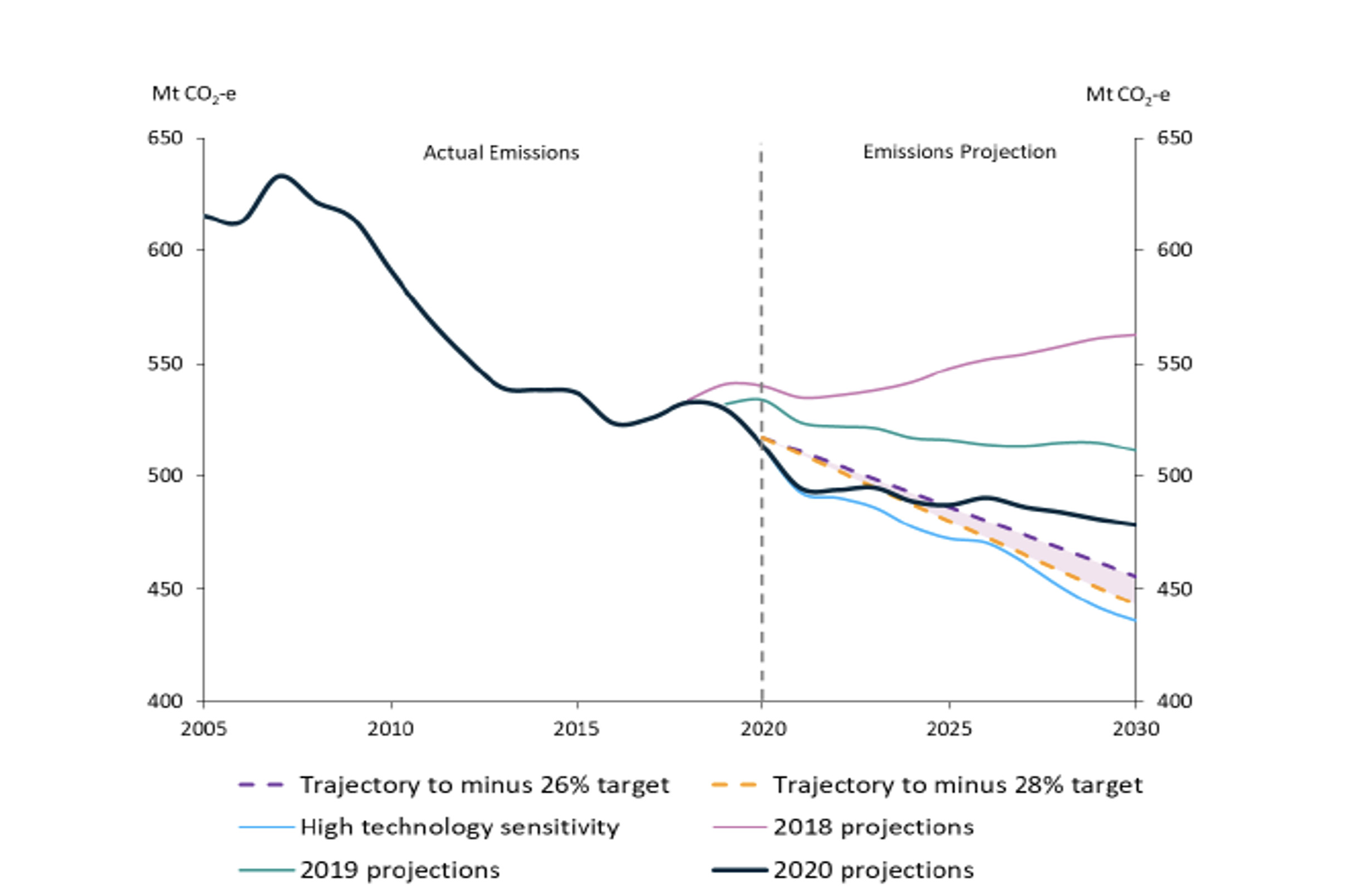

Recent government estimates suggest a gap of about 25 Mt of CO2-e (CO2 equivalent) per year by 2030, unless rapid uptake of new technology occurs (Figure 1).

While we exceeded Kyoto Protocol targets, this was largely achieved by reducing land clearing alongside a rapid increase in timber plantations on agricultural land in the 1990s and 2000s.

But the capacity to further reduce land clearing is limited, and some timber plantations have been converted back to agriculture.

Environment

What to expect at COP26

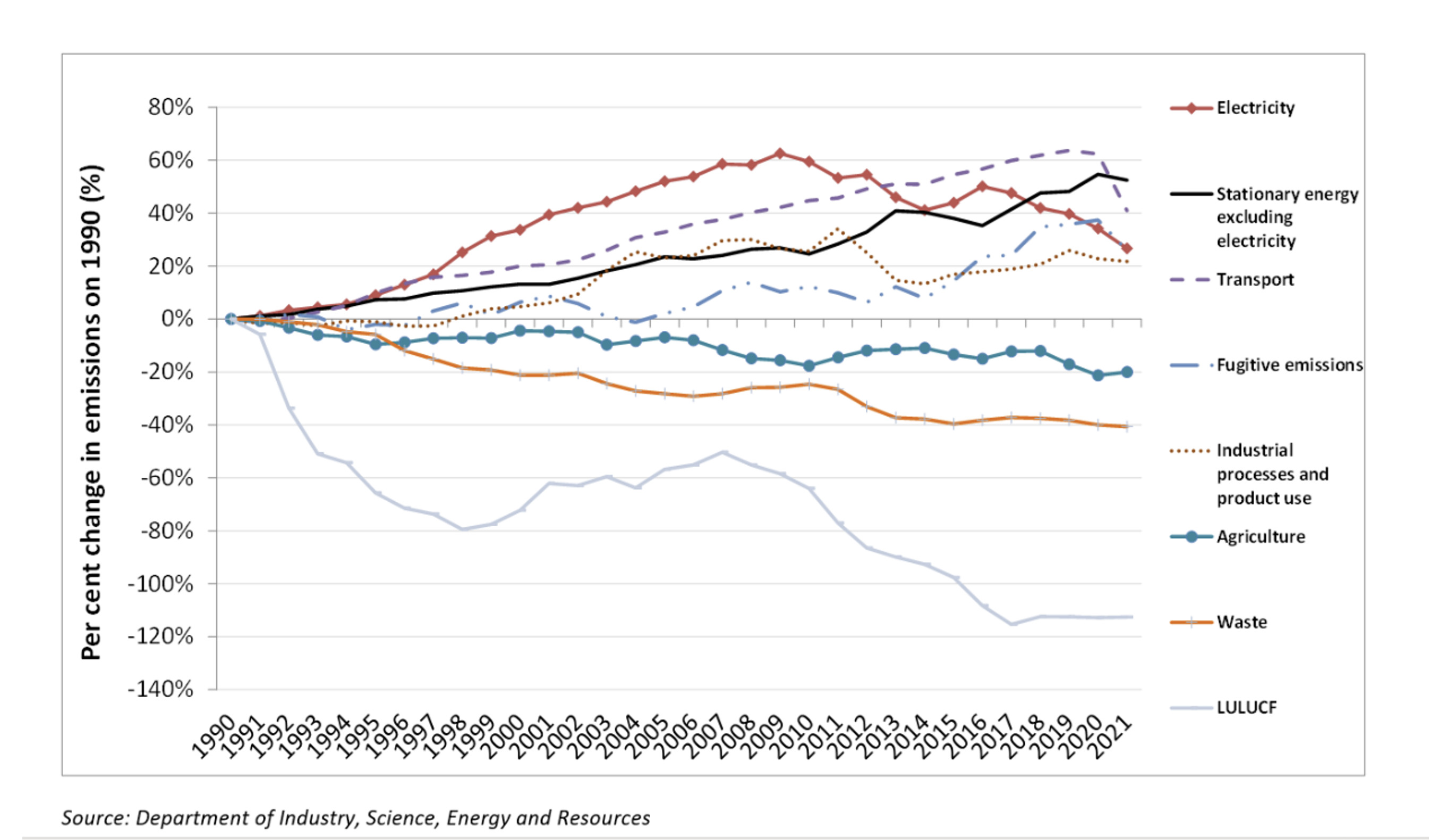

Emissions from coal-fired electricity have declined but have been replaced by a rapid increase in fugitive emissions from processing Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) and coal-seam methane (Figure 2) without the significant controversy surrounding coal, like the Stop Adani campaign.

Proponents of exported gas suggest that LNG could reduce emissions in importing countries and serve as a ‘bridge fuel’ while more investment flows to renewables.

This ignores the heavy emissions burden LNG processing places on Australia, and an overall increase in emissions in some importing countries. Investing more in LNG will potentially leave us with stranded assets, when countries inevitably turn to cheaper renewable energy sources.

National leadership

Australia lacks national leadership on climate policy, but state and territory governments are increasing climate action.

The Victorian government, for example, has a Climate Change Strategy, with a commitment to Net Zero by 2050.

But state-based approaches are uncoordinated and not well-integrated – some states have a plan to tackle battery storage for the renewable energy sector, but other states are doing much less climate mitigation or adaptation.

Local governments also have climate commitments – for example, Moreland City Council’s Zero Carbon 2040 framework – and are organising into Greenhouse Alliances. Companies and industry sectors, like the National Farmers Federation, are committing to net-zero targets.

Yet, lack of national coordination across states and territories, local governments, the private sector and the community creates difficulties for businesses in complying with different standards and codes.

Clear national goals would provide incentives for business to act on climate change while reducing legal and market risk. Currently, companies must weigh the risk of losing their social license (or possible future litigation and profit loss) against the financial risk of reducing current profits.

These decisions are difficult without a supporting, coordinated policy framework.

An australian climate accord?

Closing the gap between our current emissions and future targets requires a new governance framework that brings together relevant parties.

We propose that prior to the Federal election, the incumbent and opposition leaders put plans to the Australian public to convene a dialogue to develop an Australian Climate Accord following the next election.

This could be modelled on the 1983 business-union-government roundtable to develop the Prices and Incomes Accord between the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the Hawke government.

Health & Medicine

The betrayal of our young

Through a similar collaborative process, an Australian Climate Accord would identify barriers to change and attempt resolution, ensuring coordination between industry sectors, different levels of government and across community.

The dialogue could broker the relationships and information that’s essential to meet collective climate goals.

The Climate Accord would indicate how to reduce our emissions while maintaining or improving our living standards. It must involve Indigenous peoples, all forms of industry and levels of government, unions, farmers, members of the wider community.

In effect, this would be an inclusive, Paris-style, Australian Accord with a clear commitment from all participants to meet emission-reduction targets.

Open and honest multi-stakeholder discussions are needed to consider complex interactions between sectors and come to equitable long-term measures for deep cuts to emissions that would fulfil Australia’s international commitments.

This won’t be easy.

Despite relatively broad agreement across the Australian community, emissions reduction policy is driven by conflict. Some see political benefit in maintaining, rather than resolving this conflict.

Environment

Australia’s rivers are ancestral beings

Convening a dialogue will require deft political positioning, strong leadership and capacity to listen.

Many in the community feel disaffected and threatened by the changes needed to reduce emissions. We must recognise their concerns and move past notions of ‘winners and losers’ to develop shared solutions that work for all Australian communities.

Independent members could be key players in bringing the dialogue together.

Most importantly, defining Australia’s commitment to a climate future, our goals, and how we will achieve them should involve everyone.

An Australian Climate Accord could do that.

Banner: Getty Images