Environment

Farming the future

As climate change gives previously-obscure tropical diseases new opportunities to spread, veterinary epidemiologists are watching patterns in animal disease to help prepare for the future

Published 26 November 2017

Virus and bacterial diseases don’t appear out of nowhere, and most require a host to stay active, reproduce and evolve. Insects and other animals play a key role in this - around 60 per cent of infectious diseases that affect humans are zoonotic – which means they’re spread from animals to humans.

But this is a pattern also true of 75 per cent of new or emerging infectious diseases.

Tracking disease prevalence, spread and movement between populations of animals is the role of veterinary epidemiologists like Dr Simon Firestone, Professor Mark Stevenson and Dr Anke Wiethoelter at the University of Melbourne.

“A nice analogy would be that a traditional veterinarian’s client is a single animal; a veterinary epidemiologist’s client is the country and all the farms and animals in that ecosystem,” Professor Stevenson says.

Environment

Farming the future

Much of their work focuses on foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), a highly contagious virus that affects cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. Australia has never experienced a large outbreak of FMD, but if it were to hit our shores, a multi-state outbreak could cost up to $52 billion in control costs and lost trade over 10 years.

The 2001 outbreak in the United Kingdom cost an estimated £8 billion - that’s around $13 billion Australian dollars in today’s money.

Professor Stevenson, Dr Firestone and Dr Wiethoelter have worked with Australia’s Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, along with Dr Richard Bradhurst from the University of Melbourne’s Centre of Excellence for Biosecurity Risk Analysis, to simulate the spread of FMD under Australian conditions.

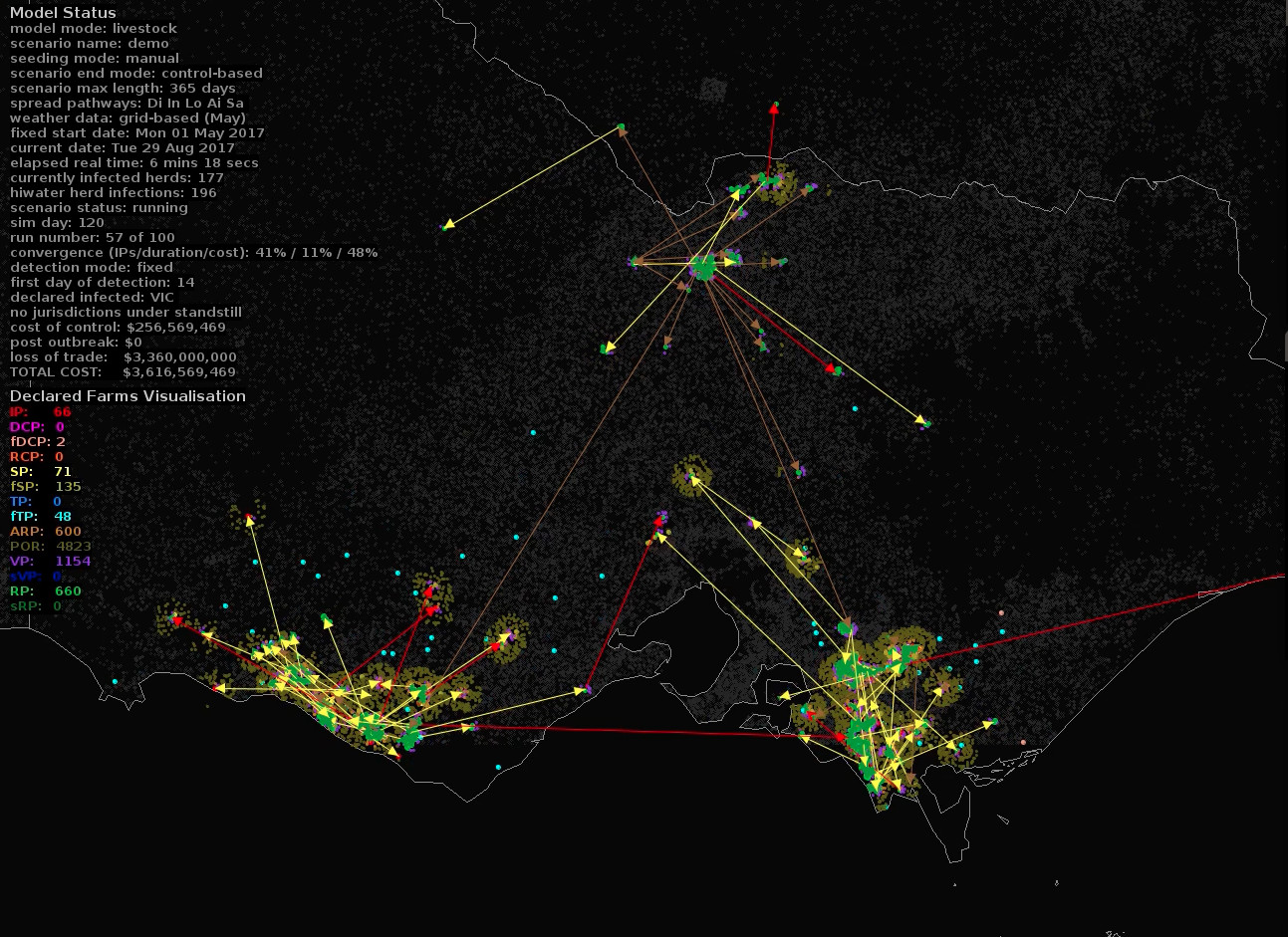

The Australian Animal Disease (AADIS) model, developed with funding from the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, maps the progression of an FMD epidemic, taking factors like weather, species, location and animal health personnel availability, into consideration.

As the effects of climate change become more apparent and existing patterns are disrupted - this kind of modelling becomes even more important.

The patterns of disease will also change as temperatures rise and weather patterns shift, says Professor Stevenson.

“The most obvious effect of climate change will be with what are called vector-borne diseases – diseases that are transmitted by insects like Ross River virus,” he says.

“And with climate change there’ll be a change in the geographical distribution of known insect vectors for given diseases.”

Environment

Dairy’s (climate) changing future

The Dengue Fever, Zika and Chikungunya virus-carrying Aedes albopictus mosquito has been present on Torres Strait islands since at least 2005, and modelling by University of Melbourne researchers has shown the daylight and cold weather-tolerant pest could spread as far south as Tasmania if it finds a foothold on the mainland. But mosquitoes aren’t the only populations on the move.

“The other thing that will probably change is the geographic distribution of human and animal populations,” says Professor Stevenson.

“Urbanisation will see people move to areas that 30 or 40 years ago were rural, and where livestock will be located will probably change too, and that will influence the risk of disease.”

Dr Firestone worked with the Victorian State Government and staff from the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity to use another model to forecast the risk of an outbreak of the mosquito-borne Ross River virus following much-needed rain in south eastern Australia last year.

The Ross River virus infection causes arthritic joint inflammation and pain, fatigue and muscle aches. In most cases, patients recover in a matter of weeks, but some can continue to suffer intermittent pain.

In October 2016, weather patterns and disease surveillance led the team to forecast a year as bad or worse than the 2010-2011 season, when major flooding contributed to a rise in Ross River infections.

“The Health Department was pretty geared up so people got the right advice to prevent mosquito bites and reduce their contact with mosquitoes, and that hopefully prevented a lot of disease,” Dr Firestone says.

“They were also working closely with local governments to spray larval breeding sites to control mosquito populations. That early warning system allowed the health department, local government and local councils to respond and reduce the risk early on.”

This approach – where animal and human health professionals collaborate with local, national and international authorities – is known as One Health.

Sciences & Technology

From racehorses to bananas: The importance of biosecurity

Here in Australia, the approach has meant the creation of a joint centre with the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), CSIRO and other partners working towards the improvement of diagnostic tests for disease surveillance.

“That is a large part of what we do with the University’s Master of Veterinary Public Health program, which has got a specific focus on emergency animal disease control. That involves training vets and animal health scientists to fulfil key roles in disease outbreak responses.”

Some diseases appear and spread rapidly. Others are well-known and monitored, but can creep across barriers via wild animal populations, says Dr Firestone.

“Rabies has spread across certain parts of Indonesia, and a lot of work is going on in the top end of Australia so we are aware and prepared to look for potential rabies incursions,” he says.

Professor Stevenson, Dr Firestone and Dr Wiethoelter agree that a One Health approach, continuing Australia’s enviable biosecurity record and training veterinarians and other health professionals will help mitigate the risk of future disease outbreaks.

Banner image and video: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources/The University of Melbourne