Politics & Society

Stepping carefully amid conflict in the Pacific

What would Australia do if the United States went to war against China? It’s a question that’s been discussed candidly behind closed doors

Published 24 March 2023

In 2006, opposition leader Kim Beazley told the US ambassador that “Australia would have absolutely no alternative but to line up militarily beside the US. Otherwise, the alliance would be effectively dead and buried, something that Australia could never afford to see happen”.

Beazley’s candour is important because he did not expect WikiLeaks to publish his remarks less than five years later.

A few days later, US Embassy staff met his principal political adviser, Jim Chalmers, whom the embassy wanted to ‘protect’ as an interlocutor.

Dr Chalmers is now a leading figure in Australian politics.

He has not yet spoken publicly on whether “Australia would have absolutely no alternative but to line up militarily beside the US”, but former defence minister Peter Dutton already declared that “it would be inconceivable that we wouldn’t support the US in an action if the US chose to take that action … Maybe there are circumstances where we wouldn’t take up that option. I can’t conceive of those circumstances”.

Politics & Society

Stepping carefully amid conflict in the Pacific

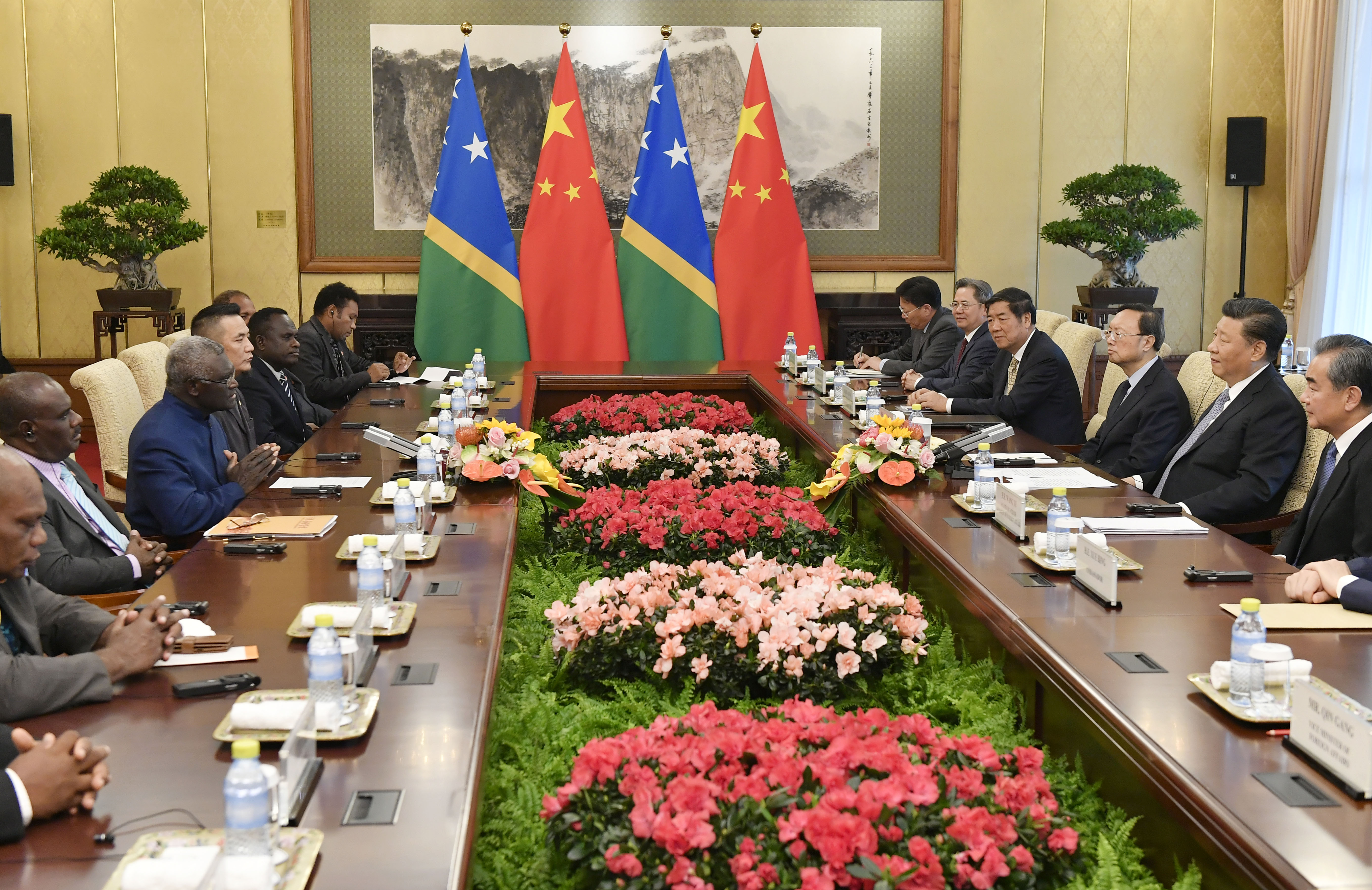

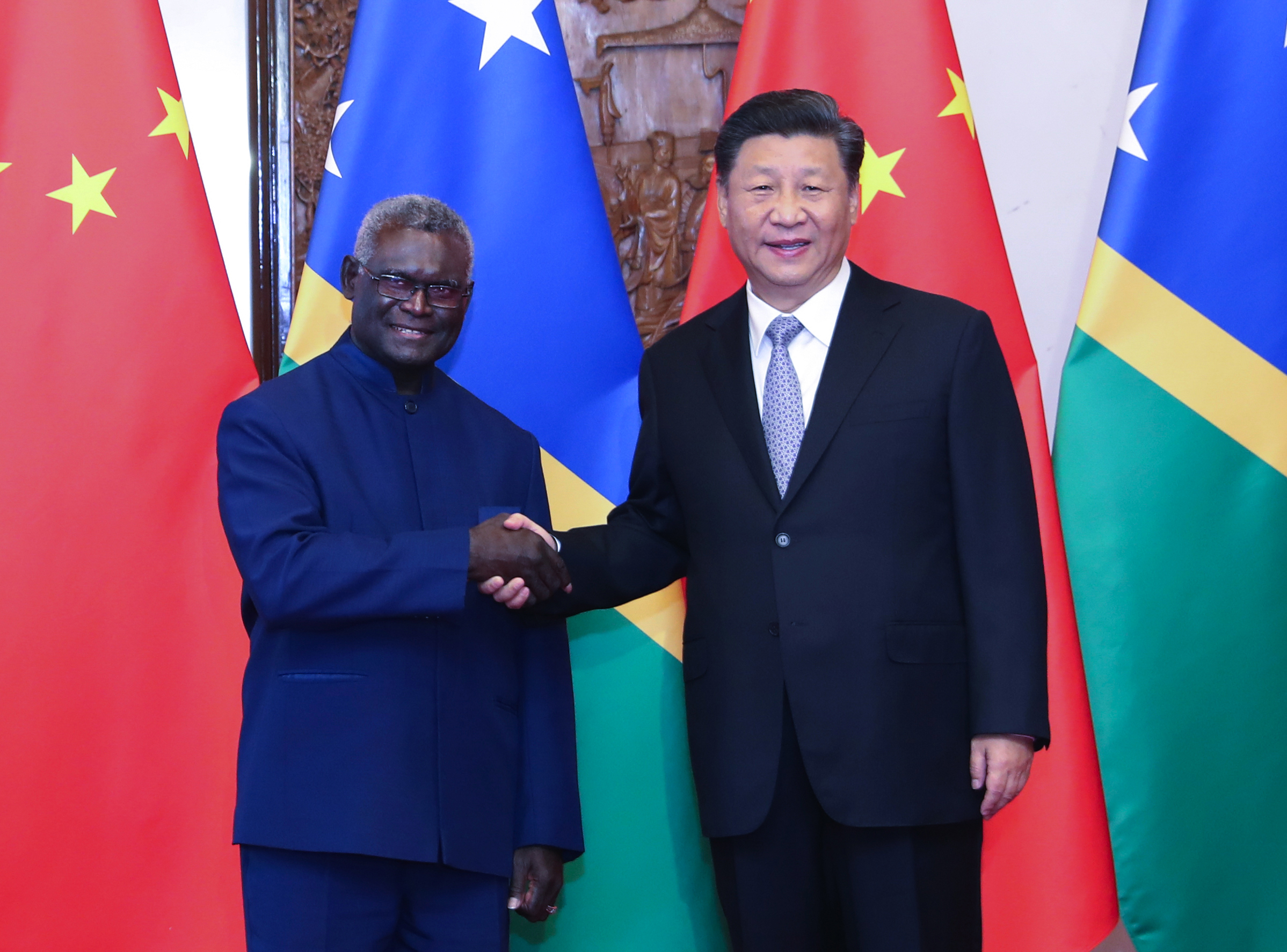

In April 2022, news emerged that China and Solomon Islands had entered into an agreement involving ship visits, logistical replenishment and other related activities. The Australian opposition at the time said it was the “worst failure of Australian foreign policy in the Pacific since the end of World War II”.

With less hyperbole, independent Senator Rex Patrick called it “Australia’s worst intelligence failure” in more than two decades and said that Australia’s high commissioner, other senior diplomatic staff, Australian Defence Force representatives, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and the Australian Signals Directorate “should all face very searching questions about their performance in what appears to be an intelligence failure of major proportions”.

Some journalists reported claims that Australia’s intelligence agencies were not caught napping.

There is a way to deal with this question, particularly since the opposition claimed to be outraged too.

The government, with bipartisan support, could declassify the intelligence it received by sanitising it to conceal the specific means by which it was obtained. Sanitisation preserves the agencies’ ability to continue to obtain intelligence on the target.

For example, the Office of National Assessments and the Defence Intelligence Organisation produce intelligence assessments that draw on communications intelligence (the preserve of the Australian Signals Directorate) and human intelligence (the preserve of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service).

Politics & Society

Southeast Asia matters to Australia

The assessments are analytical reports whose conclusions can be published without disclosing the details of technical and human sources. That would be a simple way to examine whether the intelligence agencies gave advance warning—and, if so, of what kind—without enabling foreign governments and other hostile elements to take adequate countermeasures against Australia.

The Solomon Islands has considerable challenges.

It ranked 151st in the 2020 Human Development Report, placing it in the Low Human Development category.

It is a youthful country in which seven out of ten people are younger than 30 years of age. The danger of large numbers of young people who lack income-generating activities or other outlets for their energy and ambition is well known.

The neoliberal framework within which Australia has engaged with the region has not delivered optimal social outcomes. Why would it, given its track record?

In this context, development along the Chinese infrastructure-based model might offer improvements in the standard of living. And that could send a message to Australia’s traditional vassals in the region – who are sometimes called ‘our Pacific family’.

If they see material improvements in the lives of Solomon Islanders, they would not necessarily fear closer integration with the Chinese economy.

Politics & Society

Real partnership with Solomon Islands must be based on truth

Chinese aid is attractive to Solomon Islands because it largely stays in Solomon Islands; Australian aid does not. During the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), about half the aid went towards the salaries of the Australian Federal Police.

Some of the remainder went to paying advisers to the public service, employing magistrates and running the country’s prison system.

This is a form of ‘boomerang aid’ that simply returns to Australia, since most of the foreign consultants or in-line appointees were Australian anyway. As Aid/Watch, the aid monitoring group put it, Australia was “the largest direct recipient of its own aid funding”.

The Chinese government behaves respectfully towards these much smaller countries, who in turn are drawn to China’s promise of economic development rather than ‘boomerang aid’.

They recognise that China is no alien trespasser but has long been part of the western Pacific. Chinese navigation texts referred to the island of Timor centuries ago; in the fourteenth century, a Chinese merchant wrote that its “mountains have no trees other than sandalwood in great abundance” and that “silver and iron bowls, Western silk cloth and coloured kerchiefs are traded”.

The south-west Pacific will be the scene of intensifying competition in the years ahead.

Mutual strategic empathy means understanding that China does not take a benign view of its encirclement by the US Indo-Pacific Command, which doubled its spending in the fiscal year 2022, in part to develop “a network of precision-strike missiles along the so-called first island chain”.

Politics & Society

Australia’s shared future with Southeast Asia

China, therefore, seeks to limit US and Australian interference with its operations against Taiwan, rather than to conquer Australia. As Australian journalist Christopher Joye puts it, “China’s strategic goal is to prevent Australia from getting involved in the potential conflict over the future of Taiwan’s democracy, and, more specifically, neutralising Australian and US signals intelligence and surveillance assets that would be crucial to this campaign”.

In 2013, the Philippines brought a legal case against China before an international panel. It concerned activities and claims in the South China Sea.

The panel ruled against China in 2016, finding that there was no evidence that China had exercised exclusive control historically over that body of water. China ignored the panel and disregarded its verdict.

Amid calls for China to respect the outcome, a few points should be noted.

International law expert Professor Natalie Klein points out that Japan immediately said that the judgment “had not set a precedent but was only binding as between the Philippines and China, and did not apply to Okinotorishima”, an island roughly halfway between Taiwan and Guam that is claimed by Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan.

Japan also asserts rights over the continental shelf and exclusive economic zones off the disputed Senkaku (Diaoyu) and Takeshima (Dokdo) islands, as well as from Minamitori-shima in the Pacific, but they arguably “would not meet the requirements of sustaining human habitation or an economic life of their own” as defined in the 2016 judgment.

Politics & Society

Is Australia becoming the ‘lonely’ country?

Likewise, the judgment calls into question the United States’ own claims to extended maritime zones around Johnston Atoll, which lies in the North Pacific Ocean, approximately 1,400 kilometres south-west of Hawaii, and many of the outlying features in the Aleutians or north-west Hawaiian Islands, which might not count as ‘islands’ under the tribunal’s judgment.

Related questions arise about Australia’s claims off both the Heard and McDonald Islands, located approximately 4,000 kilometres south-west of Western Australia.

According to the Australian Antarctic Division: ‘Since the first landing on Heard Island in 1855, there have been only approximately 240 shore-based visits to the island, and only two landings on McDonald Island (in 1971 and 1980)”.

Australia also relies on small and uninhabited features to claim extended jurisdiction in maritime boundary delimitations with France in relation to New Caledonia.

This is not the same as permanent settlement or exclusive historical control.

If these matters are not presented to the Australian public in a meaningful way, people cannot be blamed for thinking that China is the world’s major rogue state hell-bent on disregarding international law.

This is an edited extract from the new book Subimperial Power: Australia in the International Arena by Professor Clinton Fernandes, published by Melbourne University Press, available to buy online.

Banner: Shutterstock