Arts & Culture

Will COVID-19 end globalisation?

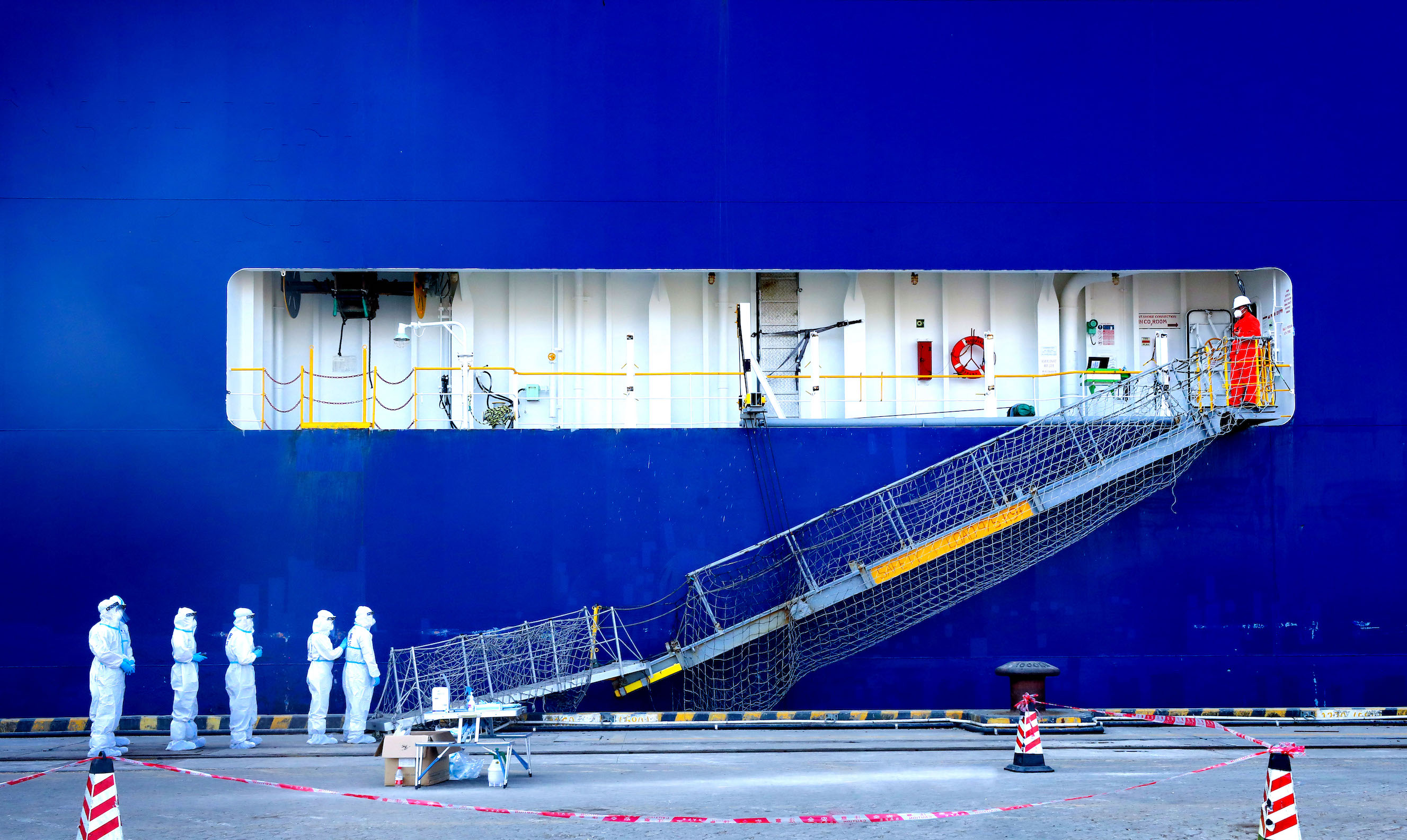

The COVID-19 pandemic has left hundreds of thousands of seafarers stranded on board ships, leading to a ‘crew change crisis’ that needs urgent action

Published 25 August 2021

Every time our city locks down, our horizons shrink to our five-kilometre bubbles and we spend most of our time at home. But there’s a COVID-19 crisis happening much further out to sea, that’s affecting millions of people’s lives and livelihoods.

More than 80 per cent of our global trade by volume is moved by maritime transport with around two million people from different countries around the world working onboard merchant ships.

As of December last year, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) estimated that around “400,000 seafarers are … stranded on their ships beyond the end of their original contracts and unable to be repatriated, due to COVID-related travel restrictions”.

And roughly the same number are onshore, urgently needed to join these ships to replace the crews stuck on them.

Just as Australia shut its international borders to keep the virus out, ships have done the same. Mostly by keeping crew changes limited to an absolute minimum.

Arts & Culture

Will COVID-19 end globalisation?

In fact, since the coronavirus crisis began, as many as one in six of the one million crew on 60,000 cargo ships at sea have been marooned.

But keeping the virus off these ships doesn’t always work.

Here in Australia, crew members from the bulk carrier MV Darya Krishna which docked in Fremantle were critically ill with COVID-19. The crew on another ship – the BBC California, an Antigua-registered vessel coming from Balikpapan on the Indonesian island of Kalimantan, tested positive for COVID-19 while docked in Western Australia.

And in this week, a cargo ship carrying 16 crew members suspected to be infected with COVID-19 is expected to arrive in Perth.

Imagine, just for a moment, that you’ve been stuck at home for eighteen months (it may feel as though you have been courtesy of lockdowns, but the reality is you’ve probably been out and about).

Then imagine that your house is where you work. You’re not ‘working from home’, because all your colleagues and your boss, the captain, all live there too.

Politics & Society

The Indonesia-Australia trade deal: A potential bilateral sandbag

On top of this, you haven’t been able to leave at all, because you’re surrounded by water.

This is the reality for the hundreds of thousands of seafarers who have been stuck at sea throughout the pandemic.

Their contracts have ended, but border closures, travel restrictions, quarantine requirements and pricey travel options make it difficult, or even impossible, for them to return home.

Even if a crew member could leave, replacement crews have to be available immediately, then and there, to change places with them because no ship is allowed to sail without the number of required crew on board.

Some of this I know from reports around the world on the crew change crisis – which has been described as “the single greatest operational challenge confronting the global shipping industry since the Second World War”.

But I’ve also experienced it all firsthand after I spent five months stuck aboard a cargo ship in 2020.

I joined the SV Avontuur in Tenerife at the end of February 2020, as part of my research into decarbonising the shipping industry, with the intention of disembarking at Marie Galante in the French Antilles. But halfway across the Atlantic Ocean, the news came that we would not be allowed ashore. Anywhere.

Politics & Society

US trade policy after Trump

“The world as we know it”, our shipowner Cornelius Bockermann told us, “no longer exists.”

Port after port remained closed to crew changes and shore leave, but the ship was allowed to take cargo (and provisions). Because supply chains and the global economy would collapse if ships stopped moving goods between countries.

Despite shipping’s importance to global trade, it took months before port states began identifying seafarers as key workers. But despite this recognition, it hasn’t meant these crews are able to travel home.

Eventually, by the end of July, we docked in Hamburg where we were allowed to sign off, after unloading our cargo of green coffee, cacao, rum and gin.

We were lucky. We were only at sea for five months.

Now you may think that many people working on these ships understand that when they are signing up, it’s for long periods at sea.

They do. But they count on being able to spend time at home with their family and friends in between stints at sea. And while these periods at sea are relatively short for captains and officers, the lowest-ranking deckhands often have little choice but to accept long contracts.

Business & Economics

Keeping supply chains ethical and sustainable amid COVID-19

Since 2006, the International Labour Organization has regulated the length and terms of contracts through the Maritime Labour Convention.

While it was a welcome change, the 11-month maximum contract length is hardly a major concession to the wellbeing of crews. On top of that, working hours are capped at a maximum of 14 hours in any 24 hours, and 72 hours in any seven-day period.

But any seafarer knows that when things get busy or difficult, these caps are breached.

On a personal level, the biggest challenge for me was not knowing when I was going to be able to go home. On a more structural level, the persisting crew change crisis means that the Maritime Labour Convention risks being eroded.

The global pandemic border closures that began in March 2020, allowed shipping companies to keep their crews on board beyond the caps outlined in the Maritime Labour Convention.

Today, crew change is possible. Not in every port, but in most. It may be more costly and difficult, but it is possible.

But many shipping companies, cargo owners and charterers are effectively driving seafarers into forced labour by making them work far longer than they agreed to. Some have even stipulated in their contracts that there would be no crew change.

Business & Economics

The COVID-19 shock to supply chains

As a result, around 200,000 people remain at sea beyond their contracts. Some of them have been at sea for more than 18 months, some longer than the pandemic has ravaged the world.

And leaving work while at sea is all-but-impossible without the express permission of the captain.

The lag in vaccinating seafarers is putting their health at risk. And it risks creating problems with global supply chains. The WHO now offers a roadmap to prioritise vaccine access for seafarers. But this remains a complex logistical challenge.

All of this not only risks damaging the integrity of global supply chains, but also the human rights of the 1.5 million seafarers who are at work aboard ships at any given time – and the many more who are at home in between stints at sea.

I don’t think we’ve asked any other workers to endure conditions like this throughout the pandemic. We should not expect this from seafarers either – whatever their rank or country of origin.

Banner: Getty Images