Health & Medicine

Gene-edited babies: What does the law allow in Australia?

Researchers believe the genetic risk factors associated with schizophrenia may eventually evolve out of existence, but does this mean the condition will disappear?

Published 5 June 2019

Could natural selection one day breed out schizophrenia?

New research has found that human evolution is gradually removing the genetic risk factors associated with schizophrenia from the modern human genome.

But the University of Melbourne research has found it may be quite some time before those genetic risk factors disappear entirely, and external environmental factors are actually working against this trend.

Drug abuse, trauma, stress, serious infections during pregnancy or a difficult birth appear to be halting the suggested decline in the number of people who are diagnosed with schizophrenia.

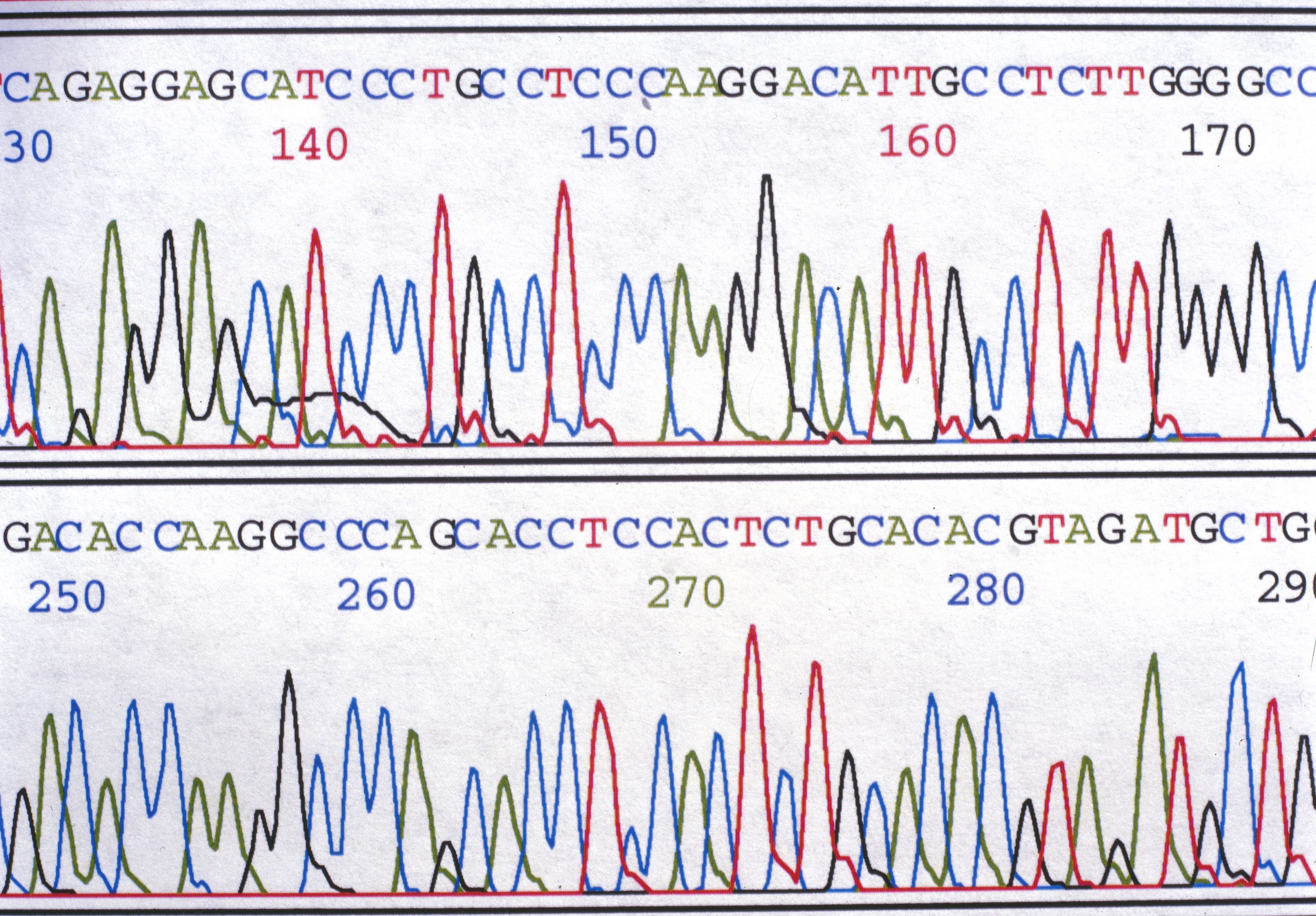

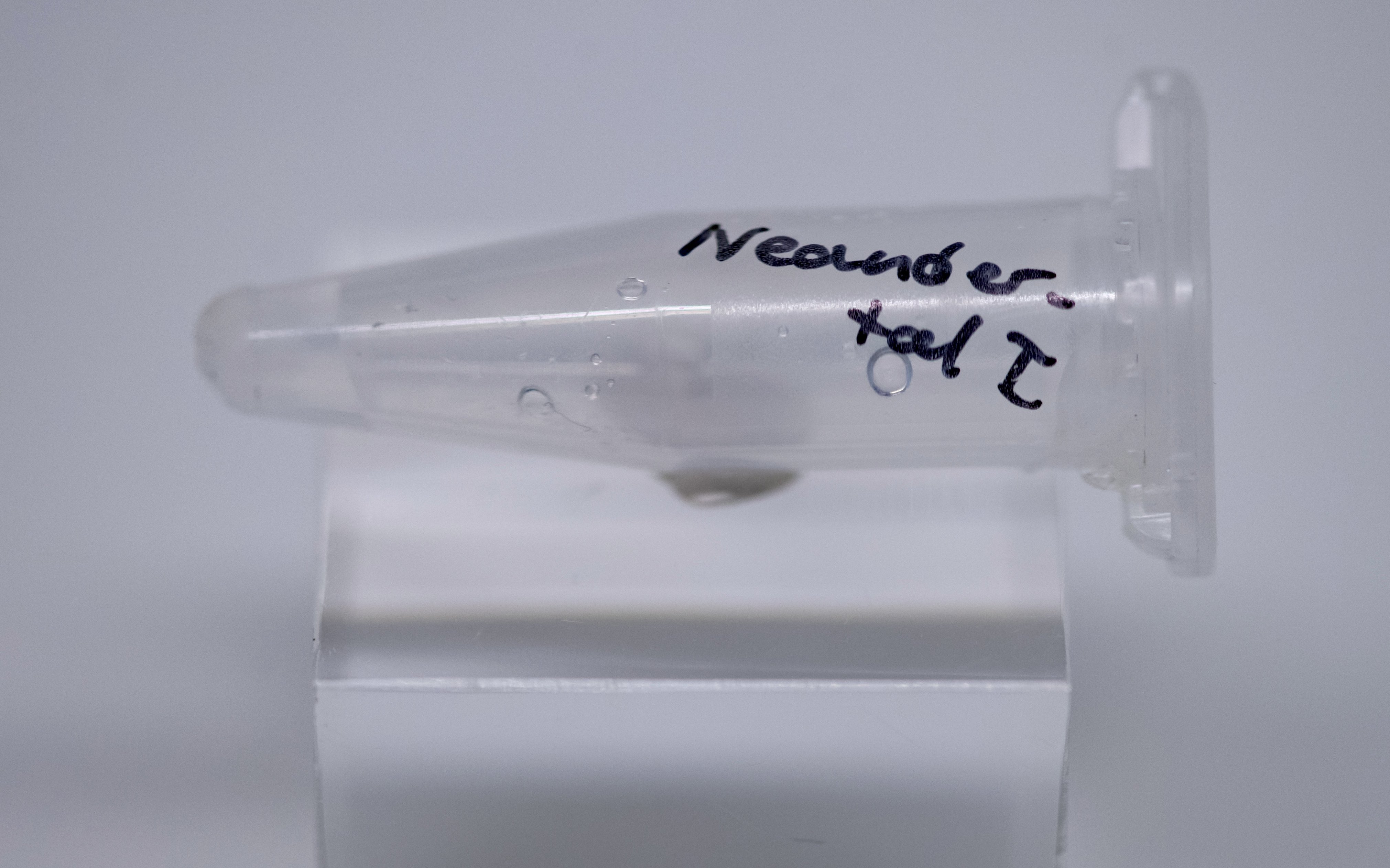

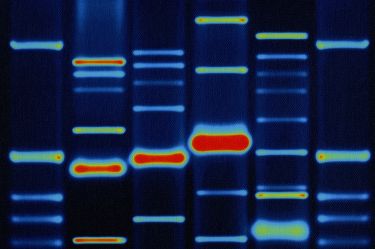

Published in Frontiers in Genetics, researchers compared the genomes of modern humans and our ancient ancestors, like Neanderthals and Denisovans. Neanderthals lived from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago across Europe and southwest and central Asia.

Health & Medicine

Gene-edited babies: What does the law allow in Australia?

The Denisovans are a relatively recent addition to the human family tree, described by one geneticist as “like an Eastern cousin” of Neanderthals.

The researchers found that the genome of our ancient ancestors contained more genetic risk factors for schizophrenia than people carry today.

The same analysis approach was also applied to look at autism, depression and bipolar disorder, but no significant differences were seen, raising more questions than it answered.

Lead researcher, Dr Chenxing Liu, found that since modern humans split from Neanderthals and Denisovans, the risk alleles for schizophrenia – the DNA changes that put you at greater risk of the disorder – had been progressively eliminated from the modern human genome.

It therefore appears that genetic risks are declining, albeit at a very slow rate.

“The findings indicate that these genetic risk factors have been gradually removed from the modern human genome due to natural selection pressure,” says Dr Liu, of the university’s Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre’s Department of Psychiatry.

“If the evolution process lasts long enough, in theory, the disorder’s genetic component could eventually disappear.”

Sciences & Technology

Human evolutionary history takes a rain check

Dr Liu explains that natural selection is a major component of evolution that constantly sorts through the variation produced by gene mutations to select the fit (positive selection) and remove the unfit (negative selection), while ignoring neutral changes.

His investigation also raised a paradox based on Darwin’s classic theory of evolution.

While schizophrenia is characterised by high heritability and reduced fertility, its prevalence has remained relatively stable – despite the new findings suggesting a decline in genetic factors. International research has found that people with schizophrenia are more likely to remain childless or to have fewer children.

Dr Liu says the illness doesn’t affect fertility physically, but it typically emerges in late adolescence and early adulthood with onset peaking between the age of 15 and 25 in men and 20 to 35 in women. So, this may affect the ability to build a stable relationship that leads to parenthood.

“So, the reduced fertility is due to being less likely to have a partner,” he says.

Dr Liu conducted the research as part of his PhD, under the supervision of Dr Chad Bousman, Professor Christos Pantelis and Professor Ian Everall.

“Our study, for the first time, provides experimental evidence supporting the role of negative selection in eliminating risk alleles for schizophrenia, but not other psychiatric disorders, from the modern human genome,” he says.

Health & Medicine

Who is paying the price of whole-genome sequencing in cancer care?

“Based on these theoretical and biological findings, we have proposed a novel evolutionary framework to stimulate further research on the evolutionary paradox and genetic origin of schizophrenia.”

Dr Liu would like to see others ‘polish’ his ideas and methods, which could be used to identify the evolutionary status of other human traits and conditions. He hopes to investigate brain size, facial morphology along with other traits and disorders to help understand how they emerge or evolve.

Further research could also identify why genetic risks appear to be declining in some human traits and conditions but not others, like certain mental disorders.

Dr Bousman, an Assistant Professor in the University of Calgary’s Departments of Medical Genetics, Psychiatry, and Physiology & Pharmacology, says it remains to be seen why the same results weren’t found for autism, depression and bipolar disorder.

“For depression the environment plays a big role,” says Dr Bousman, who has an honorary position in psychiatry at the University of Melbourne.

“However, for autism and bipolar there is a large genetic component, so I’m not sure why we didn’t find similar results.”

So how long is it likely to be before genetics can work toward eliminating schizophrenia?

“I don’t know exactly how long it would take - but it won’t happen anytime soon,” Dr Liu says. “Unfortunately, the simple answer is we don’t know.”

Banner: Shutterstock