The flu-hunters

There's a crack team of international scientists dedicated to fighting influenza, updating the seasonal vaccine every single year

Published 8 May 2017

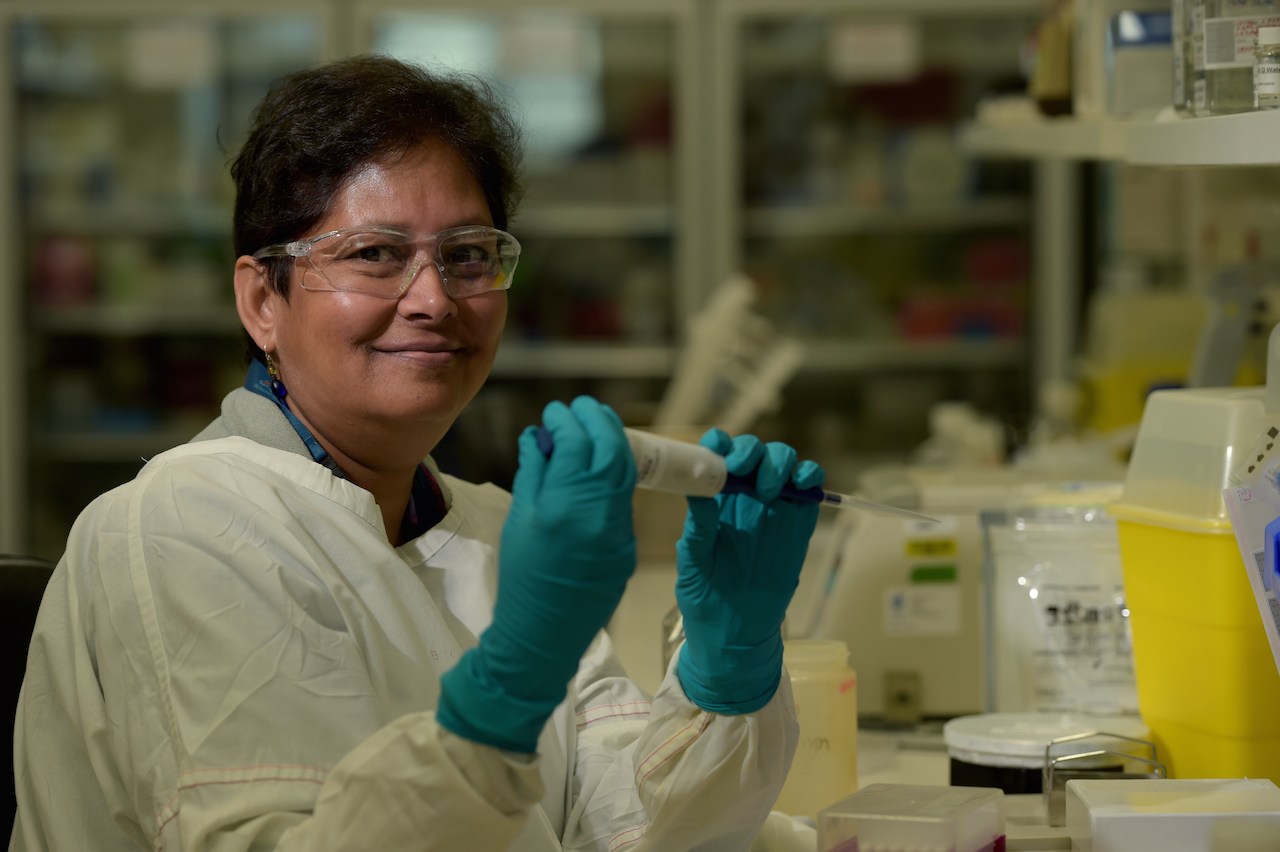

Deep in Melbourne’s Biomedical Precinct, a team of influenza specialists wait in a state of constant readiness, analysing thousands of samples from around the world.

Every year, they’re on the lookout for the next pandemic.

This team of flu-hunters are one of five World Health Organisation Collaborating Centres for Reference and Research on Influenza, tasked with the relentless monitoring of the virus as it changes form; its ability to shape-shift its greatest weapon against our immune systems.

Since the 1950s, the WHO has run this global game of catch-up, and now has 143 national influenza centres in 112 countries monitoring the virus, as part of its Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System.

Together, the five reference centres are responsible for developing the annual flu vaccine – the only vaccine updated every year.

It is, essentially, a game of detection and informed guesswork, as the international team monitors how the virus is changing each season and updates the following year’s vaccine.

The centres track everything.

From the proportion of patients visiting participating GPs with flu-like symptoms (defined as a fever, a cough and one more respiratory symptom), to patients hospitalised with flu, and outbreaks in concentrated areas like retirement homes.

“We get samples from any one of these national centres,” says Professor Kanta Subbarao, who runs the Melbourne centre for the Royal Melbourne Hospital, at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity.

“We recommend countries send us viruses if there’s anything unusual, as well as representative samples from the season.

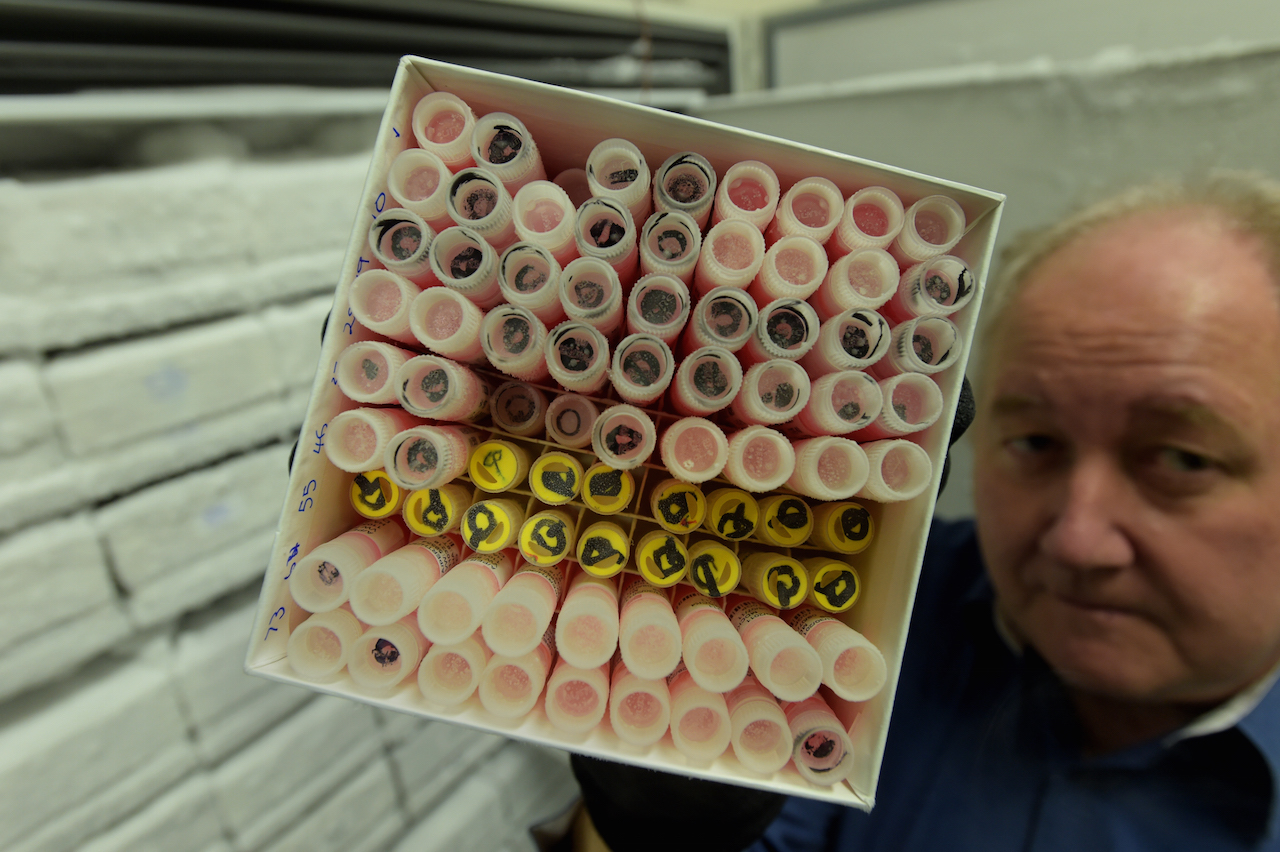

"Right now, we’re asking for four shipments a year – we typically receive about 4,000 samples a year.”

The Melbourne centre mainly receives samples from the Asia-Pacific region.

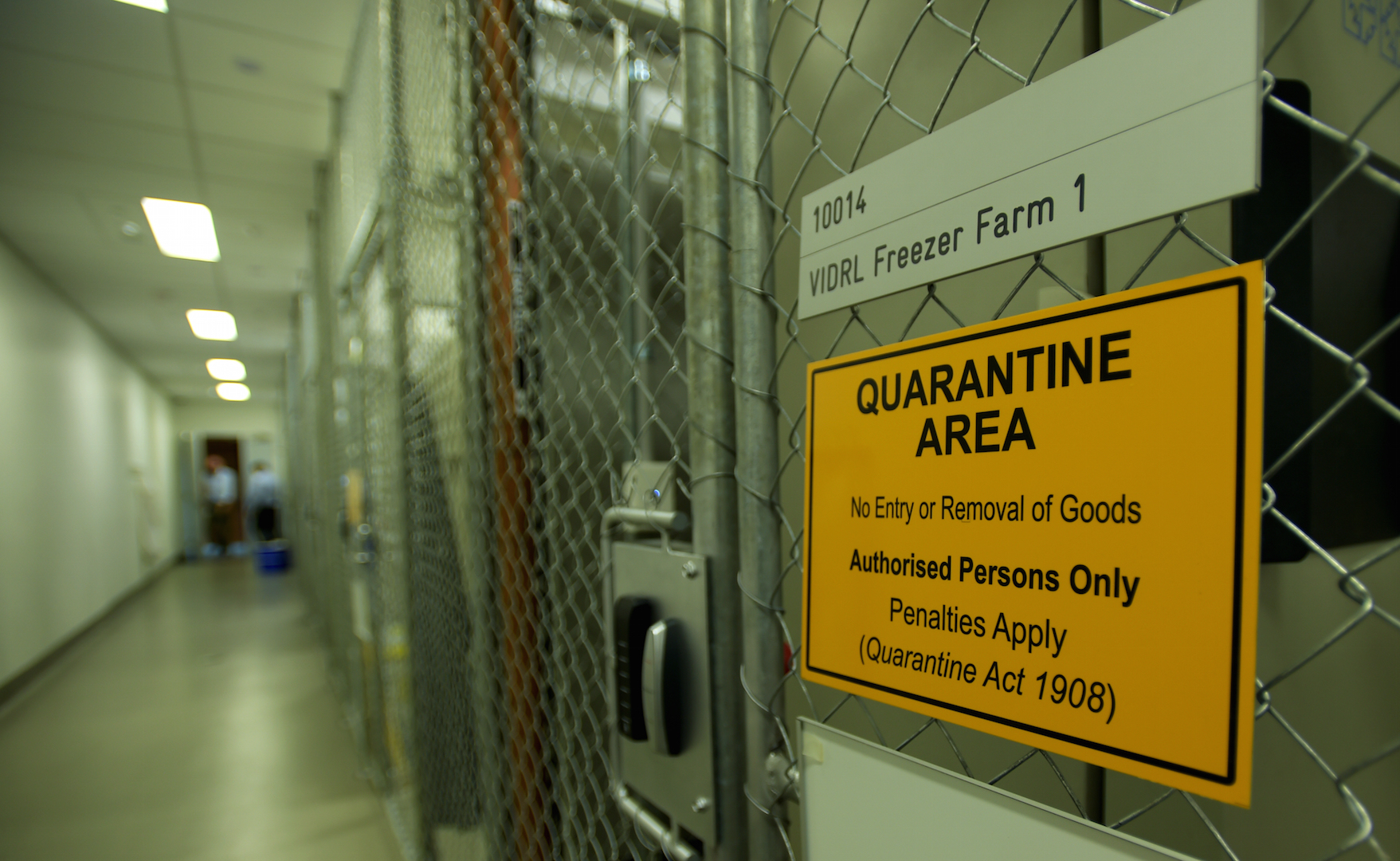

The throat and nasal swabs are packaged carefully and shipped on dry ice; they all have the potential to become the next vaccine candidate and are handled with incredible care.

The other four reference centres around the globe all undertake the same process.

Twice a year they meet; in February to recommend the vaccine strain for the northern hemisphere winter, and in September for the southern hemisphere.

From there, it takes six months to develop the vaccine.

“The two vaccines are often similar, but very often three of the four components might stay the same, and we change one,” says Professor Subbarao.

The vaccine has to be updated annually because of a process known as antigenic drift; where flu changes its appearance, accumulating mutations that alter the proteins around the outside of its virion (the infectious particle of the virus).

It essentially tricks the body into re-infection, even in people who have previously had flu.

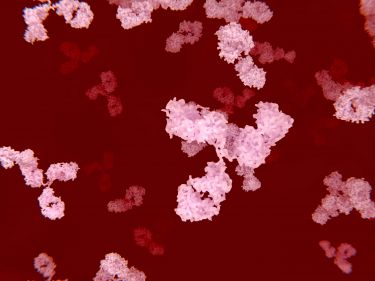

When we are infected with the flu virus, as with all viruses, our bodies’ immune response kicks in.

The first time a person is infected there is no pre-existing immunity so the virus succeeds. After a few days of infection, our B cells and T cells have multiplied to fight it.

B cells produce antibodies that are specific to the virus, binding to the flu to stop it infecting more cells. T cells take up the fight and destroy the infected cells altogether.

After someone has been infected once with a strain of flu, their B and T cells remember it.

So if they encounter that strain again, they are activated to fight it immediately, preventing reinfection.

The goal of the flu vaccination program is to produce these antibodies to prevent infection. However, because flu is a master of disguise, it can often escape existing antibody immunity.

This means the WHO flu-fighters are locked into constant surveillance of the virus, in a massively resource-intensive exercise. It also means the vaccine’s efficacy varies from year to year.

Health & Medicine

Understanding the response of our immune system’s powerful army

Some years the team can to predict the virus’ that will circulate next season more accurately than others.

Its average efficacy sits at around 60 per cent.

“The vaccine’s effectiveness depends on how well it is matched to what circulates – whether we have predicted correctly,” says Professor Subbarao.

“The other important factor is the age of a person – the vaccine is not as effective in the elderly, which is really unfortunate because the elderly and very young are the most at risk of severe complications of influenza.”

And then there’s the constant threat of the next flu pandemic.

The most recent of which was the 2009 outbreak of swine flu, originating in North America.

But the most devastating flu pandemic on record was the Spanish flu of 1918, which killed between 20 and 50 million people; more people than the First World War.

These pandemics occur through a process called antigenic shift, where the entire genetic make-up of the virus shifts and a new strain emerges – always originating from an animal host.

The WHO team are on constant alert for such a strain, but there is very little warning when the next one might occur.

“In 2009, we were all watching for a new bird flu strain, but then the pandemic came from pigs,” says Professor Subbarao.

“When we get an antigenic shift event, we basically have to start afresh with a completely new strain.

“We’re always looking for any totally novel influenza virus.”

Health & Medicine

A new monitoring tool is making vaccine rollouts safer

The knock-out punch for flu would be the development of a universal vaccine – something that has a vast international research effort behind it.

And while there has been significant progress in the lab, it's still some time until such a product becomes available.

“The science behind it is very exciting,” says Professor Subbarao.

“I think we will see a universal flu vaccine. Our current vaccines are not working as well as they should in the population at greatest risk, so we have to do better.

“I think it’ll be an incremental process; we may add things to the current vaccines to improve their protective scope and then eventually there will be the truly ground-breaking, new concept.”

Many of the universal vaccine strategies will not prevent infection; they are designed to prevent serious disease and death by targeting B or T cell immunity.

Very large clinical trials would be required to prove a strategy prevents flu-related hospitalisation and death compared to a seasonal vaccine, which is a significant hurdle to overcome.

“There’s a bit of a stand-off between where we are with the science and bringing a product to market at the moment,” says Professor Subbarao.

“There is an enormous amount of work that has to happen between exciting science and producing a final product, and that can take up to ten to twenty years, and billions of dollars.”

In the meantime, the flu-hunters remain gainfully employed.

And it's likely we will need them to be continuing their vital detective work for some years to come.