Health & Medicine

Male infertility may be the world’s ‘canary down a coal mine’

Changing social and legal perspectives of parenthood, and access to the global fertility industry has enabled a huge rise in queer people raising children

Published 6 November 2023

While researching my book Making Gaybies I saw a photograph that has stuck with me. The image was shared by a gay father I call Timothy, who is one of several queer parents I interviewed. A tall white Australian lawyer in his early fifties, Timothy had dark hair greying at the temples and a welcoming confidence about him.

The photograph depicted a Father’s Day picnic of the gay dads’ community group that Timothy convenes. A cluster of beaming, racially diverse men and babies, toddlers, and young children smiled up at me from Timothy’s iPad screen, all gathered at a lush green park on a sunny day in September.

Many of these families were multiracial, due to the backgrounds of parents and of the egg donors and surrogates involved.

In this young community, Timothy is something of a veteran. He and his Taiwanese partner, Charlie, had their son, Samuel, in 2005, when transnational surrogacy was still rare for gay men, and same-sex couples and solo Australians were banned from domestic surrogacy, in vitro fertilization (IVF) and adoption.

Longing for a child, the men travelled to California, where they conceived through commercial surrogacy and egg provision with a US surrogacy agency, an arrangement that conservative estimates would price at US$100,000-$150,000.

Health & Medicine

Male infertility may be the world’s ‘canary down a coal mine’

Timothy and Charlie are part of a growing cohort of queer people making their families in an era of increasing social acceptance and medical and legal enablement. Although accurate figures on queer family-making are notoriously difficult to obtain, the rapid rise of queer reproduction and parenting in recent decades is undeniable.

While Timothy and Charlie were among the first gay fathers through surrogacy documented in Australia, the country is now replete with queer families like theirs. The most recent Australian census, taken in 2021, documented 13,554 children living in “same-sex couple families”, compared with 10,484 in 2016 and 3,400 in 2001.

In Australia, many of these families are multiracial and transnational. Families like Timothy’s – queer couples with children born through donor conception and surrogacy – exemplify a new queer reproductive discourse, enabled by reproductive technologies, queer movements, and a multicultural notion of intimate citizenship.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the early decades of markets in fertility, queer people were outside the scope of intended users in the development of reproductive medicine, which was intended for married, infertile heterosexual couples.

And they were anathema to a prevailing colonial and Euro-American cultural imaginary of parenthood and family, which was premised on binary gender.

In these decades, reproduction among same-sex couples, solo parents, and trans people was often a spectre for straight society, sparking fierce debates and moral panics among scientists and cultural commentators.

Treatment protocols and regulatory regimes reflected a tacit and pernicious understanding of parenthood as heterosexual, by defining infertility and access to treatment in terms of heterosexual intercourse.

And explicit clinical and legal barriers prevented queer people from accessing reproductive technologies across varied national jurisdictions.

In these early decades, queer people devised ways of having children outside of heterosexual models or socially and medically ordained methods. Lesbian and queer women in Australia have a long history of conceiving children in nonclinical settings, through home insemination or through sex with cisgender men.

Gay men have often acted as sperm donors or ‘donor dads’ for lesbian and queer mothers, and many gay and queer people have conceived children together as platonic co-parents.

Queers have also historically become parents through foster care, adoption, and, to a lesser extent, altruistic surrogacy arrangements with friends or family members. Many have also had children in heterosexual relationships whom they subsequently raise in queer family structures and communities.

Health & Medicine

Freezing eggs for IVF: Waste not, want not

Although these many reproductive practices continue, since the 2000s, queer family-making has become deeply entangled with the multibillion-dollar fertility industry, expected to be worth US$41 billion by 2026. For same-sex couples and solo intending cisgender mothers, sperm banks and fertility treatment have become easier to access within Australia and abroad.

Although home insemination is a relatively straightforward procedure, lesbian reproduction has also become increasingly medicalised, treated as a medical issue to be solved through clinical intervention.

Queers thus become not just a new patient cohort for fertility care, but a key growth market from which a fast-growing commercial sector can extract profits.

Australian fertility clinics increasingly signal their rainbow allyship through explicit statements embracing lesbian, gay, queer and trans people, and they include queer-specific conception information on their websites and promotional materials.

Overseas, many commercial surrogacy agencies in India and Thailand have also courted the pink dollar prior to the closure of these industries to foreigners, explicitly advertising their “gay-friendly” surrogacy and egg-donor services.

National restrictions on fertility care and an extremely constrained local supply of donor sperm and eggs lead many queer Australians into multiracial and transnational families, involving overseas donors and surrogates or local donors who have very different backgrounds to their own.

Their family origin stories routinely involve transnational travel, the cross-border importation of sperm and eggs, and racialized and ethnic differences between parents, donors, surrogates, and children.

Health & Medicine

Understanding how to improve body image in queer men

Meanwhile, the global fertility industry promotes a dangerous idea of race as biological, with donor catalogues presenting racialized features as a kind of consumer choice. There is little guidance for prospective parents about how to navigate racial inequality in donor conception and surrogacy markets, or how to create affirming and anti-racist origin stories for their future children.

Queer people, provided they possess the requisite social and financial capital, are increasingly figured as parents-in-waiting.

Queer access to clinic-assisted conception is now commonly framed in the liberal democratic language of deservingness and universal rights, with parenthood an unquestionable desire that propels global reproductive markets.

Recent campaigns for same-sex marriage rights in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom are also central to a new queer discourse premised on coupledom and parenting. Gaybies gained visibility and a public speaking position in these campaigns, as they were often called on as advocates.

Despite expanded access to reproductive pathways and the ascendency of a liberal discourse of equality, queer family-making remains a hotly contested cultural field, with mounting attacks on queer reproductive rights globally.

The campaign around the same-sex marriage plebiscite in Australia in 2016 was a pertinent reminder that the intimate decisions and reproductive lives of queer people remain a battleground for racialized struggles over the meaning of the good life and national belonging, even as queer kinship practices have already radically reformulated the terrain of intimate citizenship.

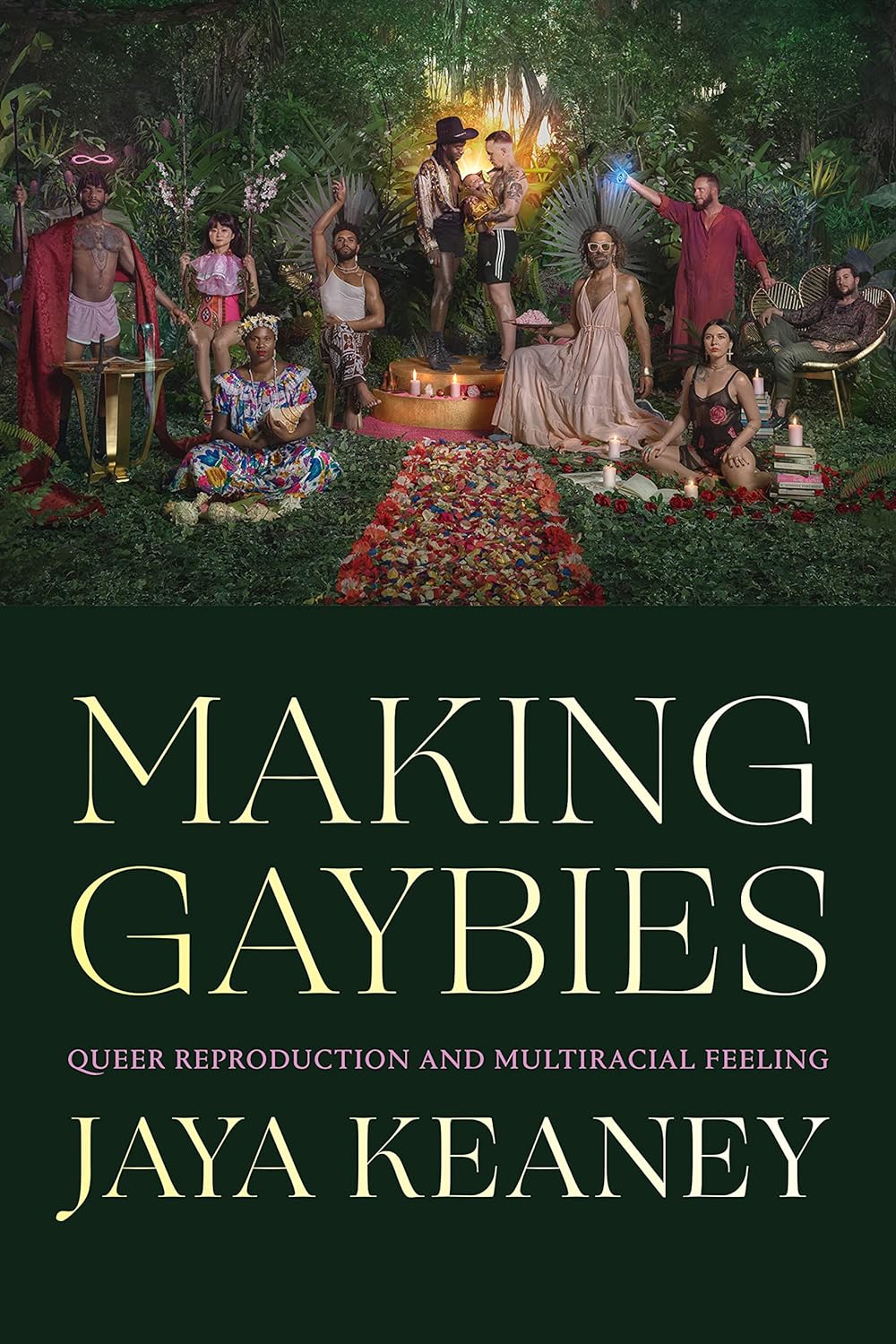

This is an edited extract from Making Gaybies: Queer Reproduction and Multiracial Feeling, by Dr Jaya Keaney, and published by Duke University Press.

Banner: Getty Images