Health & Medicine

The future of cancer is very personal

We don’t yet understand why rates of bowel cancer have doubled in young people, but new research finds DNA damage caused by gut bacteria may be part of the puzzle

Published 11 January 2024

Three weeks after her 40th birthday, Julie McDonald had a colonoscopy. When she walked into the doctor’s office afterwards, there were photos lined up on the desk.

“I knew something wasn’t right,” she says.

Julie was diagnosed with stage three bowel cancer. While she had experienced some mild symptoms, the news still came as a shock.

“I didn’t have any belly aches or bleeding. There was nothing out of the ordinary, other than I felt a bit constipated every now and then,” she says.

As a young woman, Julie didn’t fit the ‘usual profile’ of someone with bowel cancer (also referred to as colorectal cancer). But her grandfather had died from the disease, and she uncovered more incidences while researching her family tree.

Health & Medicine

The future of cancer is very personal

“If I hadn’t discovered a family history, I probably would have fobbed off the symptoms as something else,” she says. “I wouldn’t have gone to the doctor until things were really bad, and by then it might have been too late.”

People over the age of 50 have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer, but the prevalence of the disease has been rapidly increasing in young people, who now make up one in nine new diagnoses.

Rates in people aged between 20 and 39 have more than doubled from 2001 to 2021, making it the most common cause of cancer-related death in that age group.

Researchers don’t know what’s causing these high numbers yet, but it could be linked to what’s going on in the gut.

“The timeframe at which early-onset colorectal cancer is increasing suggests it is unrelated to hereditary causes, which would take generations to surface,” explains Associate Professor Daniel Buchanan, who leads the Colorectal Oncogenomics lab at the University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research.

“A potential cause of this increasing incidence is related to changes in our gut microbiome. Over the last few decades our diet, lifestyle and environmental factors have changed, which can alter the type of bacteria as well as the balance between good and bad bacteria that live naturally in our gut,” Associate Professor Buchanan says.

“This phenomenon is known as the birth cohort effect, which refers to the shared variations a group of people born around the same time experience as a result of the common behaviours and environmental factors they have been exposed to.”

Health & Medicine

What's gone wrong with managing bowel cancer in Australia?

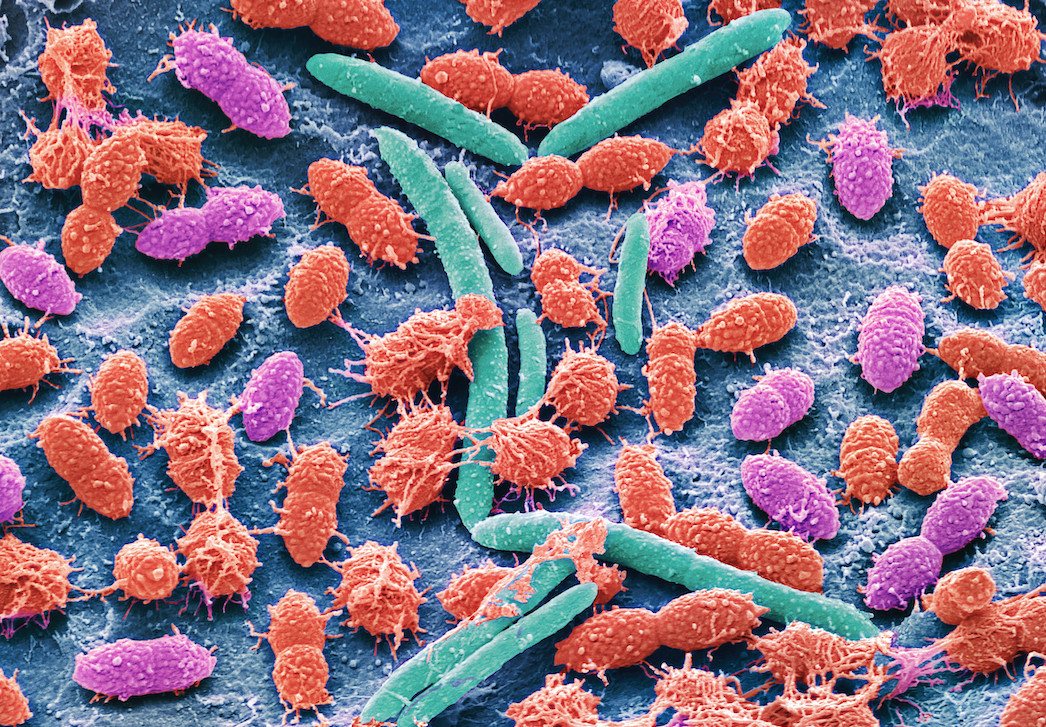

The microbiome is a complex community of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and viruses that occur naturally in and on our bodies. A healthy balance can help regulate our digestion and immune systems. When something goes wrong, it can trigger disease.

Associate Professor Buchanan’s group have just released a study analysing the role certain bacteria in the microbiome may contribute to colorectal cancer development.

“We looked at three different types of bacteria that occur in the gut, each of which produces a different genotoxin that can cause DNA damage and inflammation in the colon,” he explains.

“While most studies have analysed stool samples, we wanted to see if the bacteria were present at the scene of the crime, in the tumour itself.”

The study found at least one of the three bacteria in anywhere from six to ten per cent of the colorectal cancer cases they looked at. One strain was more likely to occur in patients who were diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer.

“We found a specific variant of the bacteria Escherichia coli that causes DNA damage by producing a genotoxin called colibactin – we can measure this specific DNA damage in the tumour,” says Associate Professor Buchanan.

“It’s the first time a non-genetic biomarker for the cause of colorectal cancer has been identified – meaning we can now link the cause of cancer back to this bacteria.”

While the presence of these bacteria suggests a person may be more likely to develop colorectal cancer, it’s not exactly a smoking gun. Not everyone who has the bacteria in their gut develops cancer.

There is work to be done to better understand what researchers should be testing for, and whether they should be looking for the bacteria or the colibactin it creates.

Health & Medicine

Using the right test for the right person to detect bowel cancer

Associate Professor Buchanan stresses it’s important for young people to know their family history and be aware of the symptoms of bowel cancer, which include rapid weight loss, irritable bowel, diarrhoea and blood in the stool – things people are often hesitant to talk about.

“Part of the reason why bowel cancer is so deadly in young people is because they tend to be diagnosed at a later stage,” he explains.

“They ignore or downplay their symptoms for longer, or maybe their GP doesn’t join the dots because it’s a disease not previously associated with young people.”

“That’s why it is so important to raise awareness, so people recognise the symptoms early and don’t delay in getting tested. Because if you catch colorectal cancer early, it’s basically a curable disease.”

While the number of young people getting colorectal cancer is going up, overall incidences of the disease have been consistently falling, thanks to the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program.

Eligible Australians aged 50 to 74 receive a free home test kit in the mail every two years under the program, which about 40 per cent of recipients complete.

In response to the growing number of early-onset colorectal cancer cases, the National Health and Medical Research Council has recently approved new clinical guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer, recommending the screening age be lowered to 45.

Professor Mark Jenkins, who leads the Precision Prevention of Colorectal Cancer lab at the University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research was a member of the guideline review committee.

“These recommendations were made on sophisticated modelling that estimated the number of cancers that would be detected early, the number of deaths that would be prevented and the cost of providing this expanded screening,” he says.

Health & Medicine

Will Australia be left behind in the cancer genomics revolution?

The federal government has said they are considering when and how to expand screening to meet these guidelines, but in the meantime, free tests remain unavailable to people under 50.

Julie is grateful her GP listened when she came in and gave her a referral for a colonoscopy.

“Other doctors would ask me if I was sure I had the right diagnosis because I was ‘far too young’ to have bowel cancer,” she says.

Since finishing treatment, Julie has been active in offering support to other patients. She started a peer-support network and got involved in Bowel Cancer Australia’s Never Too Young campaign. She’s even printed a bumper sticker for her car with her phone number on it, inviting people to give her a call if they want to chat about the issue.

If she could go back to before her diagnosis and give herself one piece of advice, Julie says it would be: “Trust your body and listen to what it’s telling you. Don’t let people convince you that you are imagining things or being a hypochondriac. If you think something is wrong, ask for a colonoscopy.”

Banner: Shutterstock