Health & Medicine

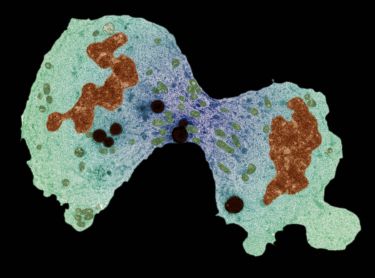

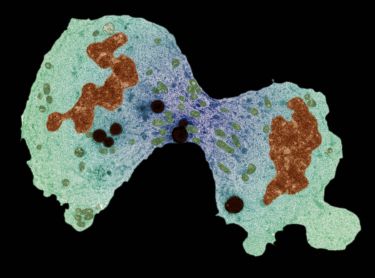

Our cancer preventing genes revealed

When it comes to caring for people with cancer, how clinicians talk about palliative care can make a huge difference to patients and their families

Published 28 August 2018

As a society, we are not very sophisticated when we talk about serious illness and death. We talk of fighting, of battling against, of staying positive and of not giving up.

Of course, this has implications for those whose illness continues or worsens. Are they losing the fight? And what does it mean about their attitude? Have they given in?

In our research, recently published in Palliative Medicine, we found the power of language is particularly poignant when it comes to how clinicians talk about end of life care. It can lead to misunderstandings, but also sadly, even tragically, to suffering and missed opportunities.

We’re looking into this at the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre’s Palliative Medicine Research Group. Based at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, our group brings together clinicians, researchers and allied health professionals, seeking to effect positive and systemic change in palliative care practice.

Health & Medicine

Our cancer preventing genes revealed

Our language around illness is reflected in the media, as we read with excitement of “a breakthrough in the fight against cancer/dementia/heart disease” – insert your illness of interest.

However, palliative care in the media and in the lives of real people, of patients, is often discussed as “there was nothing more that could be done, so they went into palliative care”.

The language that we use has direct and very serious consequences. To say that “there was no more treatment, so they had palliative care” implies that palliative care is not treatment. This language serves to limit possibilities since it negates the opportunity to choose palliative care, and the benefits that it may provide.

Why does this language matter?

Well firstly, it propagates a misperception about palliative care. Contrary to “no more to be done” and “non-treatment”, palliative care is highly effective and beneficial.

It has been proven in clinical trials to ensure better pain and symptom relief and, for many, means better quality of life than when patients are solely cared for by usual health providers such as oncology, respiratory and cardiology services.

Palliative care has also been shown to improve patients’ satisfaction with care, as they have more information and understanding of their circumstances and the choices available to them. It means they are empowered to make decisions that match their values – which, for many, means less time in hospital, and being more likely to die at home.

Research has shown that palliative care means that when people do die, their families experience less distress and have better health outcomes themselves.

And it means, based on a number of studies, that people live longer. Yes, palliative care improves survival – as much as a number of newer chemotherapy treatments. And all of these benefits increase if palliative care is introduced early.

Health & Medicine

How much exercise keeps our brains healthy as we age?

None of this sounds like “no more can be done” or a “non-treatment option”. Yet because of the language used and the associated stigma, patients (and doctors) are fearful of mentioning palliative care, much less to introduce it early.

Instead, patients think that palliative care equals death, and worse still, death in an institution “where people do things to you”, as one of our research participants said; where there are no choices.

This is the very antithesis of what palliative care seeks, and is proven to do.

And so, as if even the words ‘palliative care’ will themselves, bring about death, we avoid it until death is very close. Palliative care, raised in these circumstances, becomes linked with imminent death, and the cycle of misperception and missed opportunities (and poor care) continues.

These missed opportunities may include a lifetime of valuable things to be said to someone we love, a trip to a special place, or a chance to think through whether a further round of treatment will enable achievement of an important goal.

And poor care may include pain that is not well managed for six of the last eight months, or a young child that wonders if Dad’s illness was caused by something they did.

So what needs to be done?

We need to listen to the evidence. We need to think about the language that we use to speak about illness and death, to think about its impact for readers of today, and for patients of tomorrow.

We need to be sensitive and direct. And we need to learn to sit with the discomfort that not all is black or white, fighting or giving up, treatment or no treatment. That things that are hard to consider and face will inevitably mean hard conversations are to be had.

These conversations, though difficult, can be immensely rewarding and also may be the most important conversations for a person’s life. We all have a responsibility and a role to ensure our language facilitates understanding and choice, not its opposite.

The Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre’s Palliative Medicine Research Group is part of the University of Melbourne Centre for Cancer Research and based at St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne.

Banner image: Getty Images