Environment

Australia’s rivers are ancestral beings

Australia’s rivers and freshwater ecosystems are in trouble – a result of the false claim that water belonged to no one when the British invaded Australia

Published 11 August 2023

Nestled in a curve created by the ancient passage of Millu, the Murray River, lies Margooya Lagoon.

Sheltering under the canopy of grandmother trees, the lagoon is a place of connection for the Tati Tati peoples, who belong to this part of Country.

But river regulation has drastically reduced floodplain flows that connected the lagoon to the river, and the wetting and drying cycles of Margooya are now dictated by a water regulator, a piece of physical infrastructure that regulates water flow, on the lagoon’s downstream connection to the river.

Rather than flowing over the floodplain and through the lagoon, water is now only able to enter via the regulator, and remains pooled in the lagoon bed until it evaporates.

Margooya Lagoon is also the site of Australia’s first cultural flows management plan, created by Tati Tati to show how to care for their lagoon.

Environment

Australia’s rivers are ancestral beings

The plan uses a wetting-and-drying regime that is connected to wider land management practices, including cultural burning to clear a passage for the water at the lagoon’s upstream end, and changed watering arrangements that enables water to flow through the lagoon once more.

But achieving cultural flows at Margooya Lagoon faces numerous challenges: the land is owned by an array of government agencies, making management agreements difficult to obtain. Tati Tati Nation are not formally recognised by the settler state through native title or other processes.

And there just isn’t enough water.

In the Murray-Darling Basin, Aboriginal organisations own less than 0.2 per cent of all water rights, and most First Nations must rely on the goodwill of environmental water holders to access water.

As a result, First Nations lack the decision-making power over the way water is used to care for Country, watering continues to proceed under a Western science paradigm, and there is no capacity to use these watering events to support First Nations’ cultural economies.

The source of the challenges Tati Tati face at Margooya Lagoon is aqua nullius: the unjustified and erroneous assumption that water belonged to no one when the British invaded Australia.

Politics & Society

Returning water rights to Aboriginal people

Rather than acknowledging the long-standing, sophisticated laws and water science of First Nations across Australia, the invaders instead attempted to erase these functioning systems, replacing them with the water laws inherited from England.

In our new paper, we argue that the legacy of aqua nullius is the ongoing, unfolding sustainability disaster in the Murray-Darling Basin.

By failing to learn from the established science and law of Indigenous Peoples, settler state water management continues to impose a water management system on the Murray-Darling system that is not fit for purpose and not responsive to place.

In failing to acknowledge the legally pluralist reality of settler colonial Australia, the flawed assumption of aqua nullius undermines the legitimacy of settler state water laws.

In almost every state and territory of Australia, the right to control the use and flow of water is explicitly vested in the Crown. These statutory provisions continue to enact aqua nullius in modern Australia.

Our research argues that addressing the twin problems of legitimacy and sustainability caused by aqua nullius requires a new water management approach.

Environment

The global problem of thirsty cities

Building on the legacy of decades of Indigenous leadership and advocacy, our work explores the Cultural Water Paradigm as a holistic way of caring for and managing water, that restores power to First Nations and centres relationships between people and water.

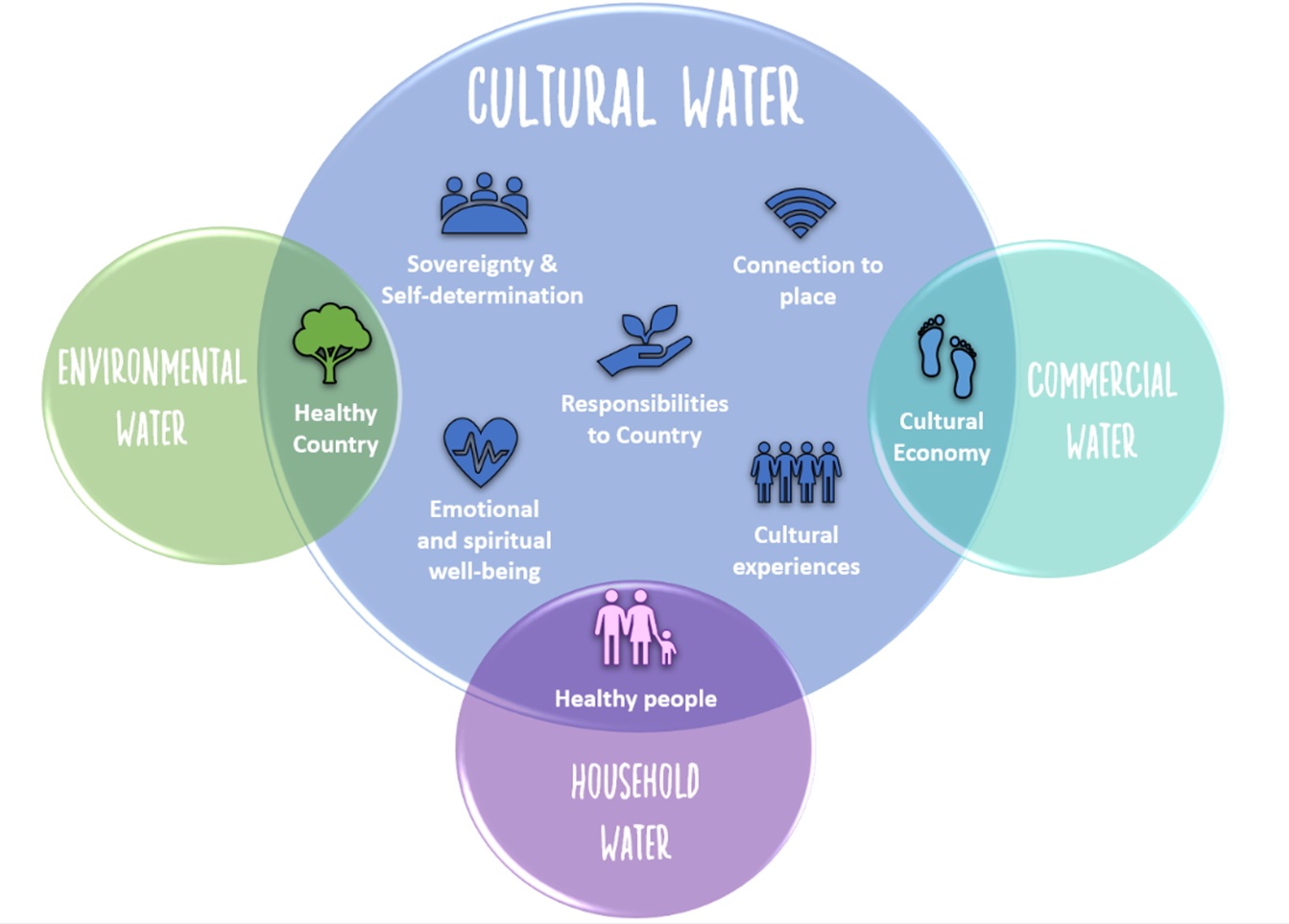

The Paradigm connects environmental health, economic development, self-determination, connection to place, upholding responsibility to Country, strengthening culture through praxis, and emotional and spiritual well-being (see the figure). Under a cultural water paradigm, First Nations are water decision-makers.

Just as ecological values of rivers depend on ‘environmental water’, maintaining the cultural traditions and community development needs of First Nations requires ‘cultural water’ guided by Indigenous knowledge (not just Western ecology).

Although centred on the Murray-Darling Basin, our work has an international side because the impacts of aqua nullius are felt in many settler colonial states around the world.

Andrew Curley, Diné (USA): “Settler states have used the idea of resources to not only dispossess Indigenous nations of land, but also water and water rights.”

Michelle Daigle, Mushkegowuk (Canada): ”The colonial capitalist dispossession of water, through the seizing of land and interconnected waterways [is] simultaneously dispossessing Mushkegowuk peoples of the sources of their political and legal orders.”

Linda Te Aho, Ngāti Koroki Kahukura, Waikato-Tainui (Aotearoa New Zealand): “The tikanga and authority of the Waikato-Tainui peoples over their lands and waterways came to be ignored as if they had never existed.”

As global momentum for a decolonial approach to water science continues to build, the strength of the Cultural Water Paradigm is its ability to overcome the barriers of Western water science and entrenched political power of the settler state.

It goes far beyond knowledge braiding, and instead offers a more radical approach that shows how to develop new knowledge, new ways of knowing and effect a genuine transfer of power to Indigenous Peoples.

Implementing the Cultural Water Paradigm at Margooya Lagoon will help address the power imbalance between the settler state water agencies and the Traditional Owners of the lagoon.

Environment

The legal rights of rivers

Enabling Tati Tati to be decision-makers on land and water management for Margooya Lagoon will help them navigate complex land tenure arrangements, as well as ensuring future environmental water deliver is led by Traditional knowledge.

In showing how to care for water in a way that connects basic human rights to water with environmental and economic outcomes, cultural flows at Margooya Lagoon can also teach settler state water managers how to achieve genuinely integrated water resource management.

Melissa Kennedy is a Tati Tati Traditional Owner and the co-founder and CEO of Tati Tati Kaeijin, a grass-roots Indigenous owned and operated not-for-profit organisation aimed at sustainable environmental practices through the progression, restoration and replenishment of culture and Country.

Banner: Margooya Lagoon/Vision House Australia