Health & Medicine

The maths and ethics of minimising COVID-19 deaths

From the bubonic plague to the Spanish flu, pandemics are not new, but the modern world brings with it amazing advancements and particular challenges

Published 5 April 2020

At a time when Australians face lockdowns, shuttered public venues, rising unemployment and market volatility, the impact of the COVID-19 coronavirus may seem unprecedented for many of us.

Less obvious is how we can judge precedent from a historical perspective.

Epidemics caused by infectious diseases are not new, ranging from smallpox to Ebola, cholera to HIV.

Recent research on the historical toll of epidemics has looked at the patterns of mortality in pre-modern and industrialised societies, as well as the longer term impacts of exposure.

Pandemics, while rarer by definition, are also not new.

Health & Medicine

The maths and ethics of minimising COVID-19 deaths

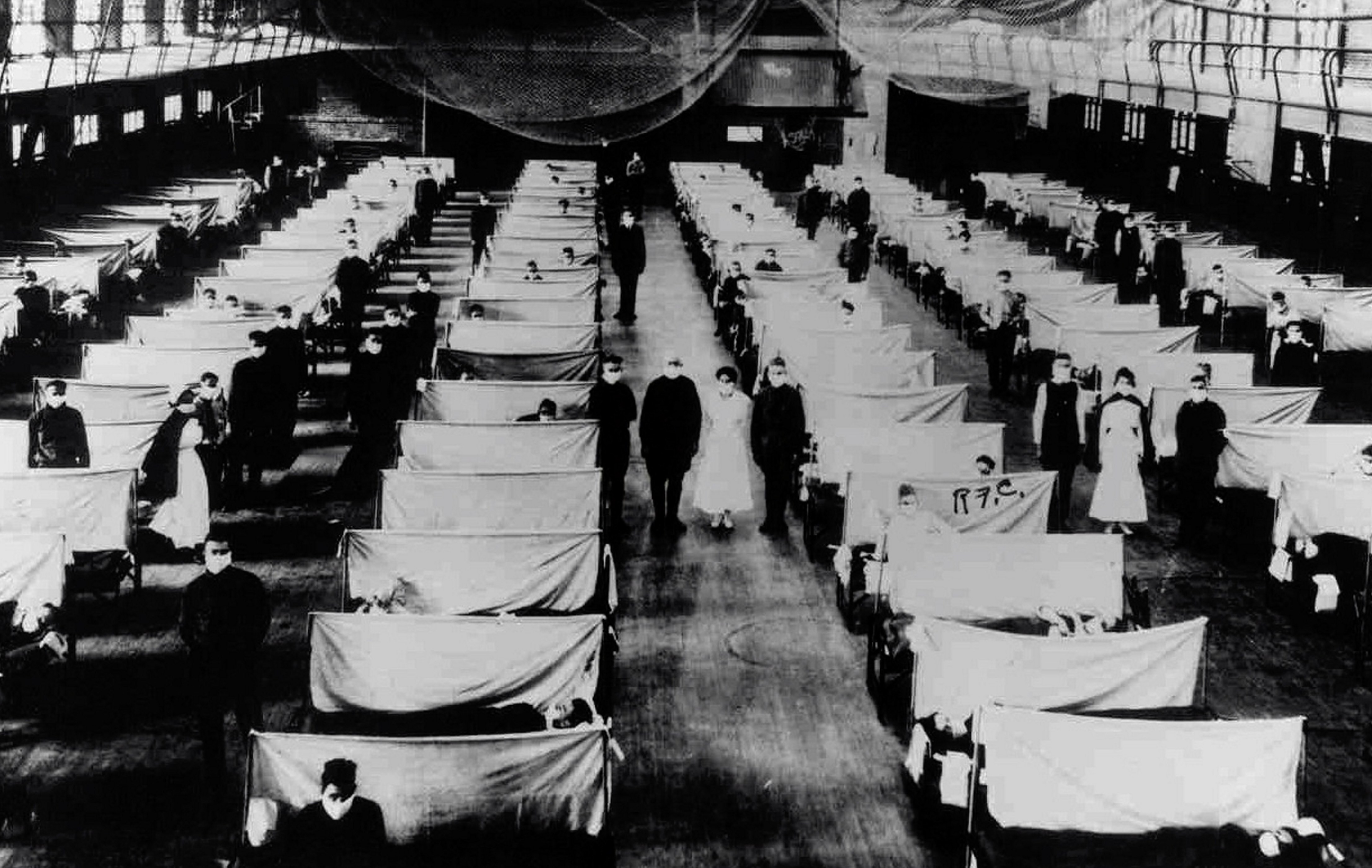

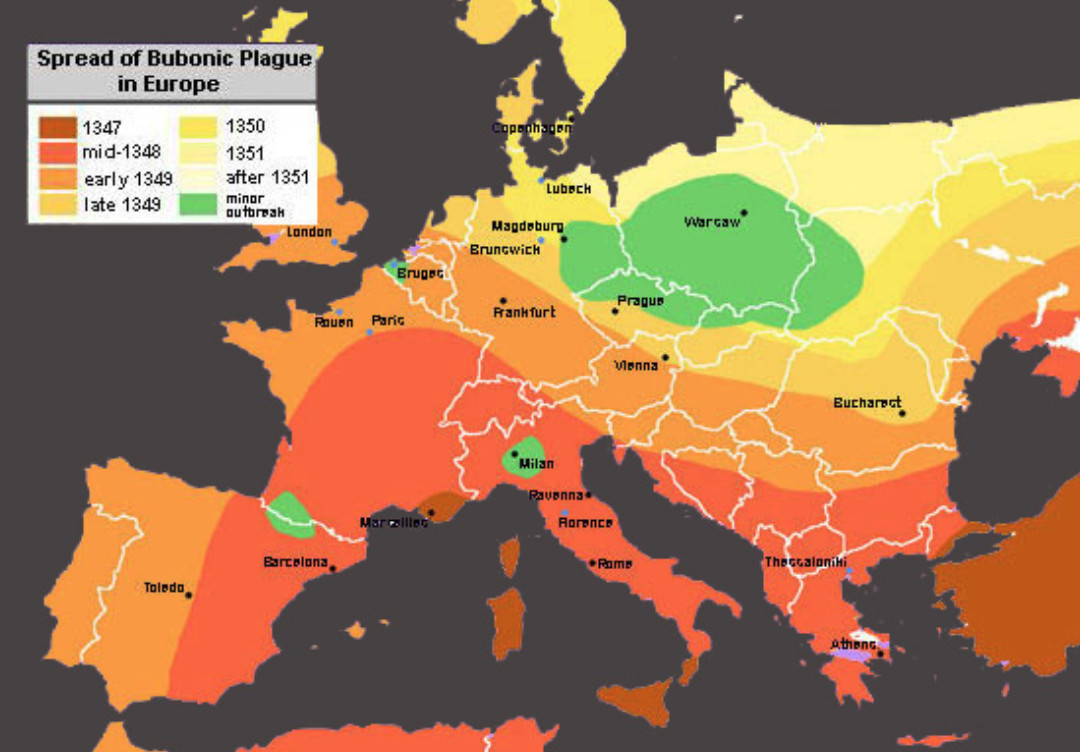

Two well-known examples come to mind: the 14th century bubonic plague (often referred to as the Black Death) and the 1918 Spanish influenza.

Each of these pandemics is estimated to have killed tens to hundreds of millions, with the Black Death particularly deadly for the elderly and frail, while the Spanish flu was less discriminatory.

Mortality rates differed substantially as well: the plague, which was carried by fleas, had a case fatality among infected people estimated between 30 to 60 per cent.

For Spanish influenza, at least 2.5 per cent of those infected died. However, given its ease of transmission via other humans, the share of the total population that became infected was much higher.

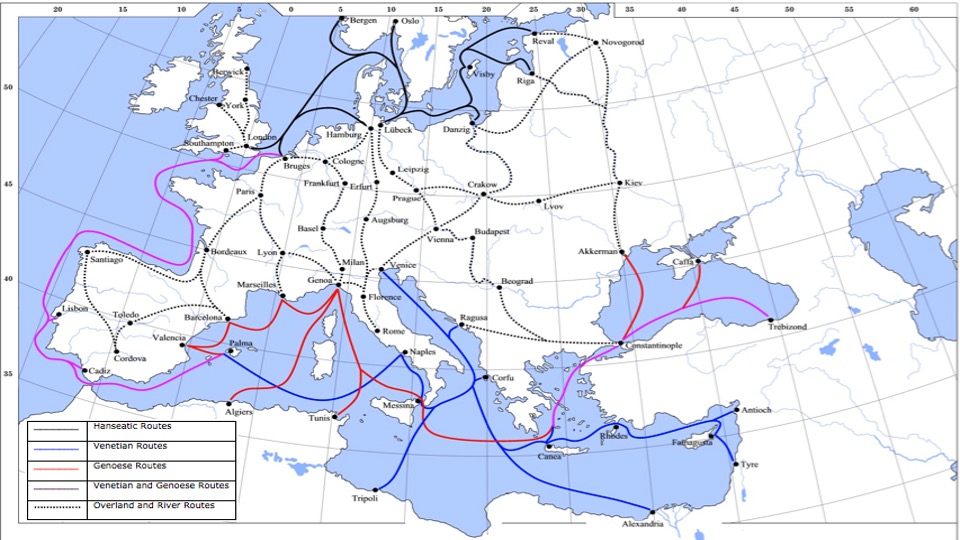

Both of these outbreaks followed patterns of human mobility: the plague spread along medieval trade routes while the influenza arrived with demobilised soldiers.

Both also lacked modern medical treatment like vaccines and inflicted multiple waves of infection and death spanning years.

Sciences & Technology

Modelling the spread of COVID-19

While COVID-19 appears to disproportionately affect older populations and has a much lower case fatality compared to the plague, preliminary estimates of infection – if there weren’t any modern medical interventions – sits at seven billion, with around 40 million deaths.

This number of deaths is similar in magnitude to the two historical examples. However, as a novel respiratory disease that spreads through human contact, COVID-19 presents a number of challenges that make it possibly more difficult to contain than past pandemics.

In 2020, we have considerations that include the relative porosity of borders and tighter global linkages. Another less discussed factor is the rapid change in our transport technology; this means the speed of human movement is accelerated.

Before the nineteenth century, humans could only travel long distances in boats which averaged approximately six kilometres per hour.

This meant that ports were often the first points of contact, with contagion spreading more slowly inland.

In the early twentieth century, the development of steam engines meant that ships could travel nearly three times faster, and the adoption of diesel engines almost trebled this speed again to nearly 50 kilometres per hour.

Sciences & Technology

Our food supply has problems with equity, not quantity

But, over the past two centuries, human mobility has diversified to include rapid transport via both land and air.

Early trains in Japan reduced a day’s walk to about an hour, while its modern Shinkansen high-speed railways shuttle passengers at speeds exceeding 200 kilometres per hour. Meanwhile, commercial airliners fly four times faster.

For diseases with a human carrier like COVID-19, modern transportation means quicker and wider transmission than was ever possible in the past.

Modern globalisation is underpinned by improvements in transport technology, which help integrate markets for both goods and people.

The swifter pace at which people now move between larger and denser populations means past pandemics are less reliable guides to predict both the duration and mortality of COVID-19.

Lessons from the 1918 influenza show that large movements of people and a lack of mitigation measures spread disease, while social distancing helped contain it.

Moreover, unlike in earlier pandemics, our modern medical treatment and surveillance are both far more advanced – reducing contagion and mortality.

Business & Economics

Oil wars, petrol prices and COVID-19

At the same time, these advantages do not appear to have changed mortality patterns separated by a century of technological change. Given the rapidity of contagion, however, governments face greater time pressure to act.

None of this addresses the epidemiological issues of disease incubation, how contagious different pathogens are, or the most effective means of treatment.

The role of transport speed on contagion also does not deal with economic considerations of whether pre-emptive action to save lives will result in outsized public debts, more powerful states, and structural changes across industries.

Even less certain is whether containment policies can be sustained over months, even years, in economies with international supply chains, large casual labour forces and food supply insecurity.

COVID-19 may not cause a lasting worldwide depression, but because the timing of contagion and policy responses are still unclear, any estimates of magnitude and variation in impact across countries would be imprecise.

What can be said is that populations and economies have ultimately rallied after pandemics.

In the cases of the bubonic plague and the 1918 influenza, recovery even followed the same transit paths taken by the diseases and were more vigorous in areas with greater devastation.

Whether those recoveries owe to common factors based on biological or economic fundamentals, or to specific circumstances remains unclear, and until then only time will tell how unprecedented COVID-19 truly is.

Banner: Getty Images