Health & Medicine

Breakthrough: Medicinal cannabis and severe epilepsy

Anaesthesia has come a long way from its origins in dentistry in 1840s America, but just how it works remains a medical mystery

Published 20 July 2017

McDreamy and McSteamy in Grey’s Anatomy; difficult but brilliant Hugh Laurie in House; dashing George Clooney in ER. TV audiences love a rock star surgeon.

But not so long ago, surgeons were called ‘sawbones’ and patients were told to literally bite on a bullet to silence their screaming. Many chose to die prematurely rather than undergo surgery. It was only the advent of anaesthesia in the mid-19th Century that made surgeons less knife-wielding Dr Moreau and more civilised Dr Watson.

Today anaesthesia is one of the safest routine medical procedures, but challenges remain and the science continues to evolve.

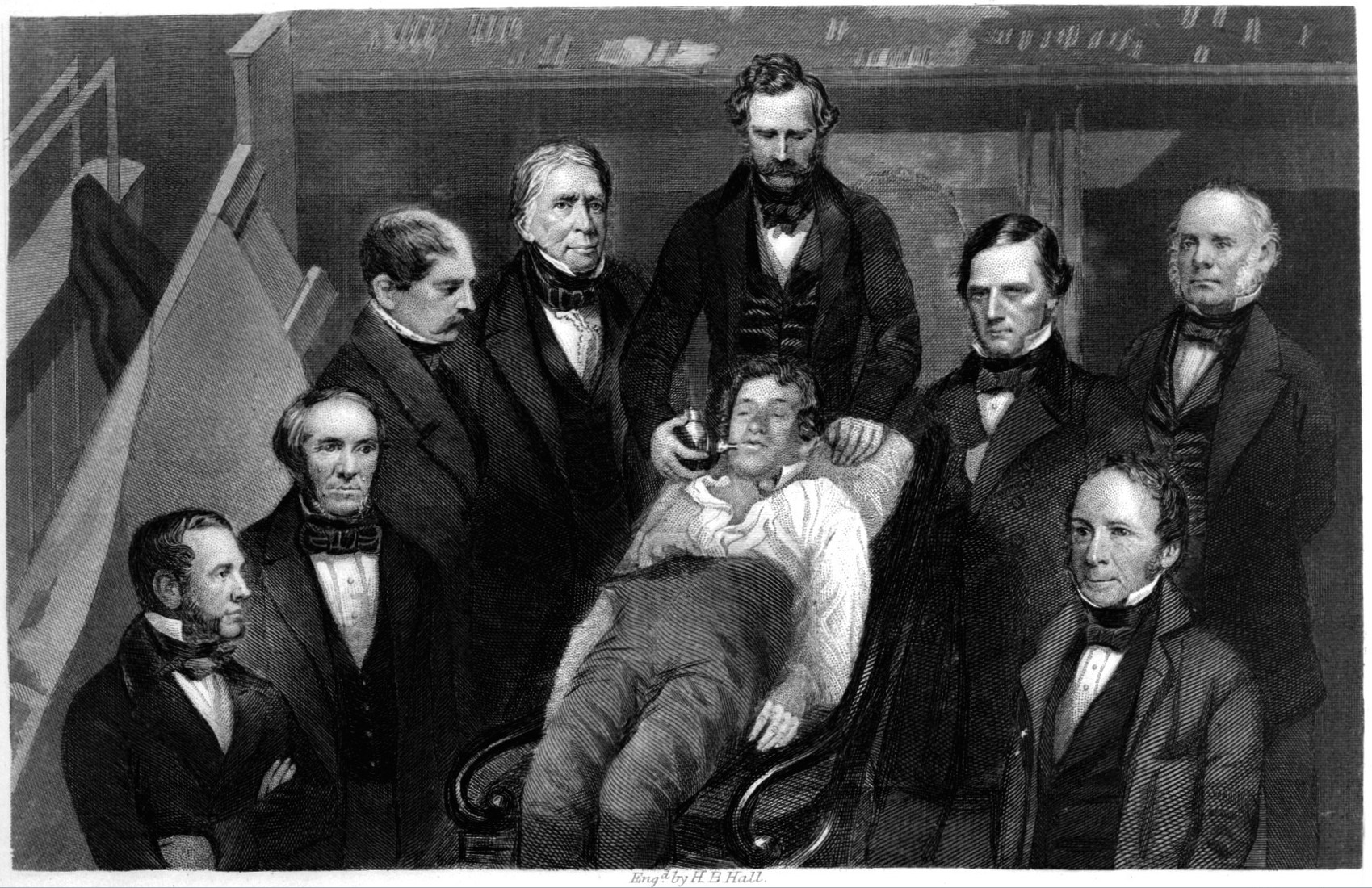

In 1846, American dentist William Morton used ether – an early example of a party drug – to anaesthetise a young male patient, allowing a surgeon to remove a tumour from the man’s jaw during a public demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital.

This news quickly crossed the Atlantic and it wasn’t long afterwards that Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson began experimenting with chloroform, which was faster acting than ether. The story goes that Simpson hosted a dinner party at his home in Edinburgh and presented a chloroform-filled decanter to his guests, eliciting feelings of elation quickly followed by unconsciousness. He experimented on himself too, making himself ill in order to advance anaesthesia.

Physician John Snow used chloroform to assist in the birth of Queen Victoria’s children Prince Leopold (1853) and Princess Beatrice (1857), popularising the use of anaesthesia in the United Kingdom. (Snow, who also proved the link between cholera outbreaks and contaminated water supply, was perhaps an early form of the rock star doctor.)

By the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865), the use of anaesthesia rendered injured soldiers insensitive to pain, allowing surgeons to complete operations – often amputations – in a matter of minutes.

In 1884, Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller used cocaine, recognised for its pain-killing and tissue-numbing properties, as a local anaesthetic for eye surgery. Although initially seen as a medical breakthrough, the drug’s toxic effects quickly became problematic until chemists were able to produce a synthesised version.

At the outbreak of the First World War, anaesthesia practice had not altered drastically from the mid-19th Century but the conflict resulted in many medical advances including the frequent use of blood transfusion and fluid resuscitation. The Second World War saw further advances including airway management, artificial ventilation and the administration of pain therapies to thousands of wounded.

Professor David Story, Foundation Chair of Anaesthesia at the University of Melbourne, says that, by 1950, the fundamentals of modern anaesthesia were in place.

“The drugs we use today are in essence the grandchildren or great-grandchildren of those used back in the 1950s,” Professor Story explains. “Ether to render the patient unconscious, opium for pain relief and curare – a South American plant extract once used as arrow poison – as a muscle relaxant to restrict movement on the operating table.

“Today’s Australian anaesthetists are medical specialists who train for more than 12 years and have a deep understanding of physiology, pharmacology and how the body reacts to drugs. This assists us in providing safe operating room care as well as acting as perioperative physicians who cater for patients’ individual medical problems.”

Today’s anaesthetists use a combination of intravenous and inhalation drugs to achieve sedation, unconsciousness, pain prevention and amnesia, while maintaining stable physiology, explains Professor Story.

“We adjust the dose depending on the patient’s age, gender, weight and health. As well as physically observing the patient during surgery, we use technology to monitor their vital signs such as blood pressure, blood oxygen levels, heart rate and breathing patterns.

Health & Medicine

Breakthrough: Medicinal cannabis and severe epilepsy

“We’ve seen huge improvements in safety over the past 30 years, with the death rate from general anaesthesia dropping from about one in 20,000 in the 1970s to one or two in every 200,000 today.”

Australians are living longer but they are sicker, which means that patients undergoing surgery often present with co-morbidities – they have the condition that brought them to the operating table and one or more additional diseases or disorders like diabetes and high blood pressure.

“But anaesthetists are increasingly good at recognising these risks and dealing with them one by one. Before a procedure, we meet with a patient to discuss their lifestyle and medical history, which helps us in assessing their individual risk factors and personalising a care plan for before, during and after surgery,” says Professor Story.

“Smoking is a good example: if we know a patient is a smoker, we can encourage them to cut down two weeks before the surgery and this also cuts down their risk of infection.”

Obesity is another example. Professor Story and fellow researchers have recently published The Mum Size Study on caring and planning for obese women giving birth by caesarean.

A collaboration between seven Victorian hospitals affiliated with the University of Melbourne and led by specialist obstetric anaesthetist Associate Professor Alicia Dennis, the study looked at the duration of caesarean section operations for 1500 patients and found an increase in total theatre time, surgical and anaesthesia time and increased risk of intensive care unit admission.

“We propose a new classification of body mass index at delivery that takes into account gestational weight gain so women are correctly classified at caesarean section, helping us anticipate extra time in theatre and modified clinical monitoring in the perioperative period,” says Professor Story.

Arts & Culture

Bones of contention

“The results of the study should inform health policy and assist with the development of interventions targeted at young women prior to pregnancy.”

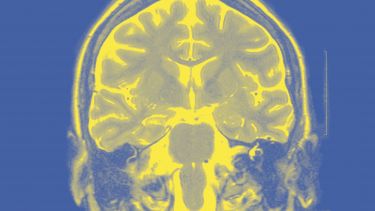

Another challenge yet to be solved is exactly how anaesthesia works. One hundred and seventy years after William Morton used ether during his public demonstration, just how these drugs render a patient unconscious remains a mystery.

“There is still a lot we don’t know about the human brain and consciousness. But our current understanding is that intravenous anaesthetic drugs target receptors for neurotransmitters – brain chemicals that transmit signals between nerve cells – particularly one called GABAA, which sends signals for responsiveness to the cerebral cortex. When this pathway is blocked, arousal signals are inhibited and sleep is induced. However, the gas anaesthetics have a broader effect on brain cells.” But achieving this low level of brain activity is a fine balance – too much anaesthetic could adversely affect the brain while too little could result in the patient feeling the cut of the scalpel and regaining consciousness mid-surgery; a rare but deeply distressing event. Until technology is created that can better monitor consciousness, medicine must continue to rely on the experience, compassion and skills of anaesthetists. Which begs the questions: why is it always surgeons playing the rock star on TV? Move over Meredith Grey, it’s your anaesthetist colleague’s time to shine!

Banner image: iStock