The one-two punch threatening to knock out the Australian film industry

A 100 per cent tariff on films and a streaming market saturated with overseas content threatens not only Australia’s film industry, but also our unique film culture

Published 19 May 2025

In early May, the US President Donald Trump announced a forthcoming 100 per cent tariff on “films produced in foreign lands”.

It is unclear whether ‘films’ means any screen content or just content made for the cinema. It is also unclear whether there may be exemptions or variations.

The catalyst for this move on the movies is the tax incentives offered by many countries, including Australia, to lure large budget productions (mostly American) to produce on their shores.

This is perceived by the Trump administration as taking work and investment away from the US – yet another ‘unfair trade practice’ demanding retaliation.

But there’s another element to this story.

For some years now, the major US-owned streaming services have resisted pressure from the Australian industry and government to impose ‘Australian content’ quotas on their activities here.

The argument for quotas is based on the huge revenues earned from Australian subscriptions: shouldn’t a meaningful proportion of this income be spent on producing Australian stories that foster Australian culture and identity on our screens?

The argument against is essentially a free trade argument.

Quotas are a government-imposed ‘restraint of trade’. Many commentators have suggested (although the Australian government has not confirmed) that US streamers are using the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement of 2005 to back their case.

Chapter 10 of that agreement does forbid the imposition of quotas that did not already exist at the time the FTA was signed.

Of course, back in 2005, streaming did not exist at all, so there were no quotas in place.

And despite hard lobbying from the local industry, quotas are still not in place, so currently streaming services are not obliged to produce any Australian content at all.

They do produce some, but at a much lower level than the proposed quotas. The exception to this is Stan, an Australian-owned streamer which chooses to produce local content at some scale.

This suggests that US screen industries do not like ‘trade restrictions’ – like content quotas – being imposed on their activities.

But in a seemingly contradictory move, they don’t seem to mind imposing them on others.

At first glance, the proposed 100 per cent tariff could be even more disruptive to the Australian industry than unregulated streaming.

The Australian screen industry’s ‘Location Offset’ and the ‘Post, Digital and VFX (PDV) Offset’ offer foreign productions a 30 per cent rebate on film and streaming production expenditure in Australia.

According to Screen Australia’s latest Foreign Drama Activity Summary, this expenditure totalled $AU768 million in 2023-24 across film, television and streaming.

This figure is 13 per cent below the five year average but still represents a huge amount of production activity and employment, particularly at our big studio complexes in Melbourne, Sydney and the Gold Coast.

The ‘movie’ sector of our Australian industry will be severely disrupted by huge jobs and skills losses if US studios and production companies no longer come to Australia because the films they make in this ‘foreign land’ must be sold into the US market for two times their production cost.

But this debate could obscure what in many ways is the more significant issue for the Australian film industry, perhaps best explained by this emphasis – the Australian film industry.

Current economic activity in the Australian film industry is mostly generated by these large visiting foreign film productions.

It is film industry activity in Australia, but it is not Australian in a cultural sense.

The proposed tariff would reduce that activity, but it will also apply to wholly Australian movies – the much rarer and distinctively Australian ‘indie’ film.

Most of our great iconic films have been (and will continue to be) of this nature: Australian stories created and made by Australians, with an Australian ‘voice’.

Even though they are made on much smaller budgets, the tariff wall will still make it harder to sell these films to the US.

Australian films already struggle to compete with international (particularly American) films at the box office.

International films have bigger production budgets, bigger stars and bigger marketing budgets, which makes them more attractive to audiences, and so potentially more profitable.

And some of those international films are made in Australia via the tax credit incentives (i.e. funded by Australian taxpayers).

Last financial year, around $AU214 million was spent on local Australian theatrical feature films, 42 per cent down on the previous year, and 49 per cent down on the five-year average.

This compares to $AU645 million spent on international features, which itself was about 15 per cent down on the previous year.

Even before the proposed tariffs arrive, Australian films – which tell Australian stories and derive from Australian creative intellectual property – are struggling in competition with international offerings.

So amid the uncertainty and disruption of the tariff landscape, there is a deeper, more important question to consider: how can we preserve a place for the ‘Australian voice’ on our cinema screens and, to pick up our earlier point, on our streaming screens?

Streaming quotas designed to protect and encourage the production of Australian small screen content (and limit American activity in our market), and tax credit incentives designed to encourage US studios to increase their activity in our market, are both now regarded by the US as unfair trade practices.

Arts & Culture

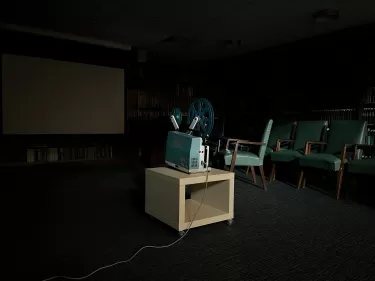

16mm films should be experienced, not just seen

But by denying quotas (‘freeing’ trade) and imposing tariffs (‘restricting’ trade), US pressure from both ends will significantly impact not just economic activity in our small and large screen sectors, but also on culturally Australian activity.

The Australian voice, and all it represents for Australian creative endeavour and Australian cultural identity on our screens, is the principle at stake here.

Donald Trump might say, “‘Tariff’ is the most beautiful word in the dictionary.”

And we might retort, “No, ‘Quota’ is the most beautiful word.”

It's clear that in the screen industry, as in all spheres, beauty is in the eye of the beholder.