Arts & Culture

The Queen who defied the Holy Roman Emperor

Contrary to Putin’s propaganda, Ukraine’s history is long and has echoes amid the war now raging

Published 25 March 2022

On 17 September 1939, Russia – in league with Nazi Germany – invaded Poland without provocation or any formal declaration of war. Russia’s declared objective was to unite the Ukrainians and Belarusians who lived in Poland with their kin in the Soviet Union.

Vyacheslav Molotov, the Soviet Minister for Foreign Affairs, declared that for this purpose 600,000 Soviet troops were to extinguish Poland – nothing was to be left of “this bastard of the Treaty of Versailles”.

If this sounds eerily familiar, it’s because it is.

Ahead of his unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin had asserted that “Ukraine never had a tradition of genuine statehood.”

But the sovereign histories of both Ukraine and Poland are much deeper than Putin’s propaganda claims.

Much of the analysis of Russia’s invasion has focused on the most recent history of East Central Europe – parallels between Putin’s Russia and Stalin’s Russia, the history of the Cold War and the Soviet Union’s former sphere of influence.

Arts & Culture

The Queen who defied the Holy Roman Emperor

But the relevant history goes back further.

It includes the redrawing of national borders by the victors of World War II, the invasion of Poland, the Bolshevik suppression of Ukrainian independence during the 1917 Russian revolution and the eighteenth century partitions of Poland-Lithuania – a country destroyed with the active leadership of Russia, and a country within which Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine had previously coexisted for more than 400 years.

The generosity of ordinary Poles towards Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s current aggression demonstrates the deep affinity between the two peoples. This should be no surprise because today’s embrace of Ukrainian refugees builds on the collective memory of the peoples of East Central Europe, and it resonates with the echoes of the events that tore Poles and Ukrainians apart over 200 years ago.

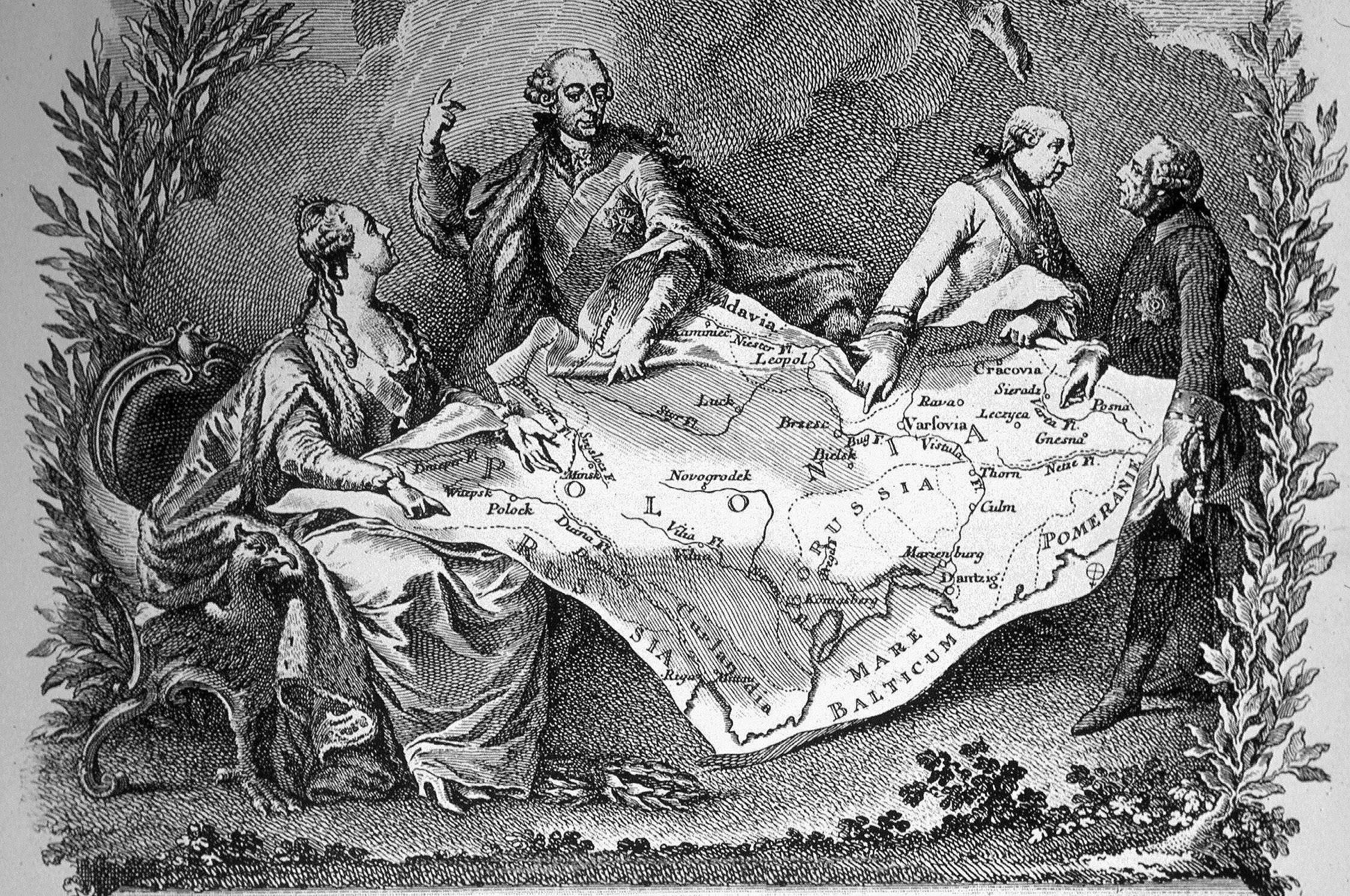

Russia sponsored the partition of Poland-Lithuania between itself, Prussia and Austria, and from 1772 to 1795 progressively removed Poland-Lithuania from the map of Europe.

This act of destruction simultaneously neutralised the political, economic and social threat to Russia’s empress, Catherine the Great, posed by a progressive neighbour and delivered significant territorial gains.

In words reminiscent of today’s commentary on Ukraine, the partition was condemned as the “most flagrant violation of natural justice and international law” by American diplomat and scholar Henry Wheaton (1785-1848) and an “immoral act of appropriation” by British writer on international relations William Hall (1835-1894).

Ukraine’s sovereignty goes back further still.

Its capital Kyiv was a centre of culture and knowledge for Eastern Christianity, predating Moscow’s 1547 claim to overlordship of “all the Russias” by hundreds of years.

Arts & Culture

Understanding modern attacks on Gandhi

Ukraine’s ancient roots go back to the Kyivan Rus (originating from settlements of Vikings) when Kyiv’s ruler, Volodymyr I the Great (c. 958–1015 CE), decided to be baptised in 987/988 CE, bringing his realm into the orbit of Christianity.

The monarchy of Kyivan Rus incorporated parts of what is now modern Belarus, Ukraine and Ru bssia, and was centred on Kyiv and Novgorod.

The medieval “Kyiv Chronicle” presents Volodymyr’s acceptance of the new religion as a deliberate act. Volodymyr studied religions practised by neighbouring nations – Islam, Judaism and Christianity – but was particularly taken by the splendour of the Byzantine ritual practised in Constantinople.

This decision was reinforced by his marriage to Anna Porphyrogenita, the daughter of Byzantine Emperor Romanos II, which ushered in the Christianisation of Volodymyr’s subjects.

Volodymyr’s son and successor, Yaroslav the Wise (c. 978–1054 CE, supported the expansion of Christianity and gained fame for codifying the kingdom’s customary law, building churches in the Byzantine style and commissioning mosaics and frescoes.

The Mongol invasion of the Kyivan Rus in 1240 marked the decline of Kyiv and it was gradually incorporated into a powerful ascendant monarchy of Lithuania under its Gediminid dynasty.

The unique feature of the Ukrainian Christianity that developed over the centuries within Poland-Lithuania was the Ruthenian Uniate Church.

It was established as the result of the 1596 Union of Brest (in what is now Belarus), when the Orthodox Church in Poland-Lithuania broke with the Eastern Orthodox Church to join with the Catholic Church.

Politics & Society

Southeast Asia matters to Australia

Its successor today, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, is the largest Eastern Catholic Church in the world with approximately five million members, and is the third largest Christian denomination in Ukraine.

In 1772, during the first partition of Poland-Lithuania, the major powers of Prussia, Russia and Austria annexed more than one third of its territory – this is equivalent in size to the state of Victoria in Australia.

Poland-Lithuania’s neighbours “masked an act of conquest” by arguing that the aggression would assure peace and preserve the balance of power in the region.

In a propaganda offensive that accompanied these events, they proclaimed themselves the saviours of Poland-Lithuania, painting the country as a “stereotype of decay, failure and retribution.”

The Western European powers, Britain and France, simply acquiesced.

This time around, Europe and the US have galvanised to support Ukraine. They may have read the history. But Putin clearly hasn’t.

Banner: Getty Images