Politics & Society

Is Indonesian democracy still trapped in old-style politics?

President Duterte promised to decentralise government in The Philippines in favour of a federal one. But will the upcoming parliamentary elections make it harder?

Published 6 May 2019

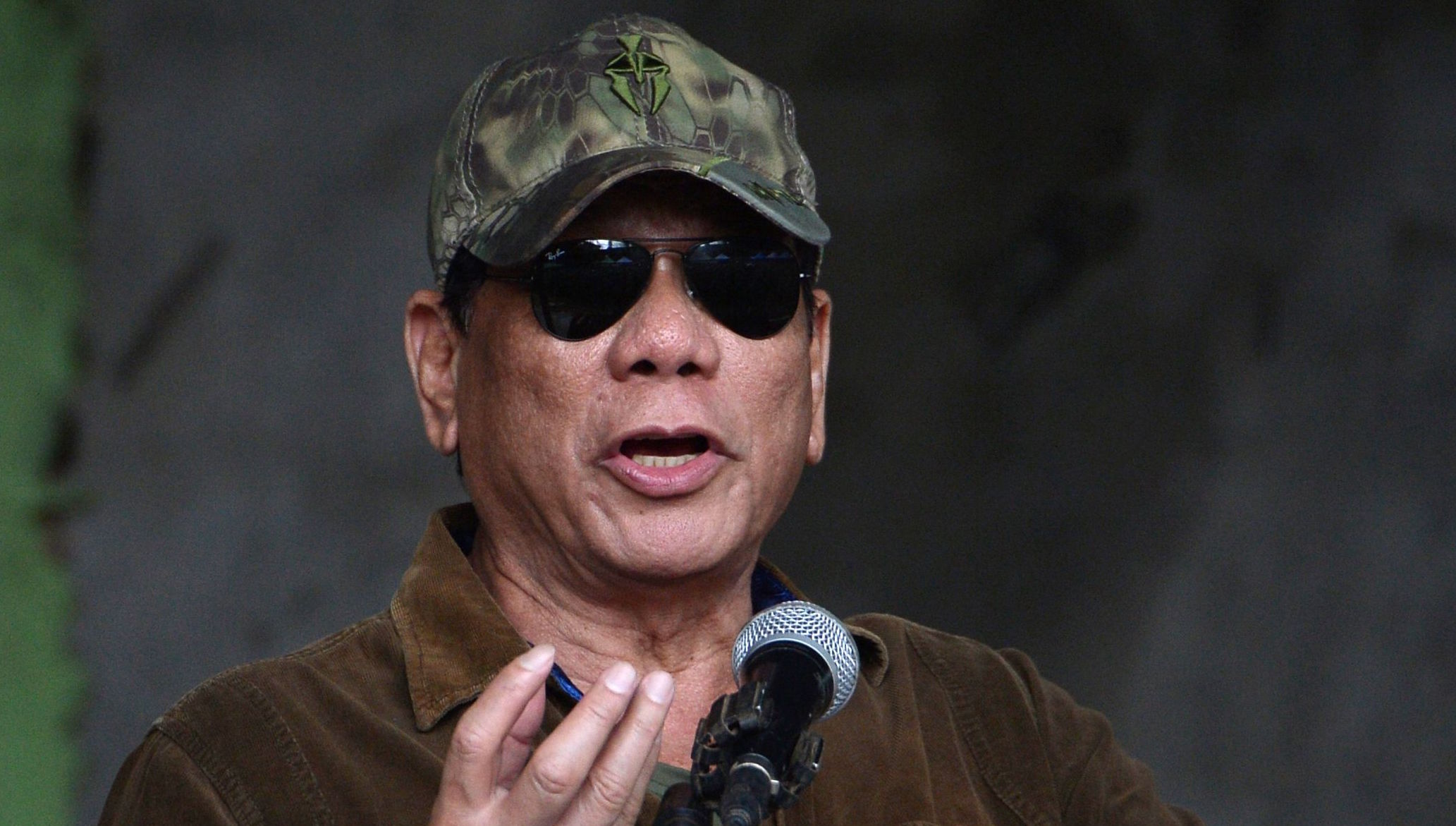

Most Australians are aware of Philippines’ president, Rodrigo Duterte, and his controversial war on drugs. But his 2016 election victory came on the back of two major promises – one to eliminate drugs, and the other to replace the Philippines unitary model of governance with a federal one.

With a parliamentary election coming up on 13th May, this second promise is now in the spotlight.

Federalism – a system of government whereby power is distributed between a central government and regional or provincial governments – is the most secure form of decentralisation. In the Philippines, it is seen as a way to break the stranglehold of ‘imperial Manila’, and to help bring peace to the restive southern island of Mindanao, which has the largest concentration of ethnic minorities in the Philippines.

Mr Duterte’s federal proposal to promote development reflects an increasingly common response to ethnic conflict and pressures in the region.

Politics & Society

Is Indonesian democracy still trapped in old-style politics?

In 2017, Nepal implemented its new federal constitution as one way to share power following a ten-year civil war. In Myanmar, the new democratically elected government established a process by which the country would establish ‘genuine federalism’, with autonomy for minority ethnic groups.

Sri Lanka also completed a wide public consultation program on constitutional change and devolution, to strengthen existing federal features and prevent the reassertion of a Tamil independence movement.

In each case, federalism is being designed to hold together ethnically divided states and respond to conflict and secession threats.

The Philippines has been a highly centralised and unitary state for more than a hundred years, whether under the colonial structures of the US, the authoritarianism of Ferdinand Marcos, or a democratically-elected president.

Marcos and others pursued a nation-building agenda and tried to forge a common identity. But this was rejected by many in Mindanao, where the culturally distinct Bangsamoro peoples have been demanding autonomy.

Democratisation in the late 1980s brought a new constitution and the prospective establishment of autonomous regions in Mindanao, and in the Cordillera (the Indigenous lands of northern Luzon - the largest and most populous island in the Philippines). But conflict continued in Mindanao, while the proposed autonomy law for the Cordillera was rejected in a plebiscite.

Democratisation has brought many things to the Philippines, but it didn’t bring much development for regions outside Manila. Nor did it bring peace.

Politics & Society

India’s alliance politics

Mr Duterte, who is from Mindanao, came to office with a pledge to end hyper-centralisation and to bring peace to Mindanao through the establishment of federalism. Fulfilling this promise remains high on the agenda.

Recent legislation establishing a new Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Mindanao alleviates significant pressure. But many other federal advocates remain, not least of all the Moro National Liberation Front’s (MNLF) founding chair, Nur Misuari, who as recently as March threatened war if the shift to federalism doesn’t occur.

It has now been three years since Mr Duterte took office, and progress towards federalism has stalled. It took almost two years for Mr Duterte to establish an expert committee to draft a new constitution. But its efforts were quickly rejected by the people and the parliament.

A Pulse Asia survey found that 62% of respondents weren’t in favour of changing the system of government to federalism. Only 28% were in favour.

Parliament meanwhile substantially revised Mr Duterte committee’s draft, making it a fundamentally ‘unfederal’ federal constitution. It also removed several provisions that might have inspired popular support, such as a ban on political dynasties. Many remain suspicious that the shift to federalism is a ploy to extend presidential term limits and allow Mr Duterte to establish a dynasty.

Politics & Society

Australia’s cuts to aid go against national interest

Mr Duterte isn’t up for re-election this month. His term continues until 2022. Whether he continues to prosecute the case for federalism will depend on the extent of support he receives from the newly elected parliament, particularly the Senate.

Mr Duterte’s party, PDP Laban, has federalism as its main agenda. But when he won the election in 2016, just three members of the house were members of his party. Party discipline isn’t strong in the Philippines and many MPs switch parties to join or oppose the ruling party. Within a month of Mr Duterte’s 2016 election, over one hundred MPs switched to his side.

However, he wasn’t able to secure a majority in the Senate, which has thus far opposed his push for federalism.

This time around, a raft of party-cross overs cannot be expected - they already know who the president will be. So, the parliamentary election results are even more important. Can a unified parliament and president turn the tide of public sentiment? This mid-term election will be pivotal in determining the future of the Philippines.

Two more electoral judgements will soon highlight the potential of federalism to mitigate ethnic conflict and to facilitate democratisation in Asia.

In Sri Lanka, the constitutional crisis of late 2018 involving the sacking and then reinstatement of the prime minister, was linked to the question of federalism. This issue will continue to dominate internal politics in the lead-up to the presidential election later this year. We can only hope that the recent terrorist incidents in Sri Lanka bring communities together, rather than re-opening old fissures.

Arts & Culture

Rebuilding cultural heritage after disaster

In Myanmar in 2017, world attention shifted from its ‘democratic transition’ to its treatment of the Rohingya people. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims were forced to flee due to ongoing religious and ethnic tensions and the Myanmar government refuses to recognise the Rohingya as ‘indigenous’ and therefore entitled to citizenship.

The federal constitutional reform process remains the key to peace and democracy in the country. Next year, the public will get a chance to pass judgment on the leadership of the National League for Democracy and its once iconic leader, Aung San Suu Kyi. Hampered substantially by an ongoing role for the military in government and the parliament, the NLD has so far failed to deliver the ‘genuine federalism’ that it promised.

These three upcoming and pivotal elections in ethnically diverse countries are about to tell us just how far a new generation of federalism can go in Asia.

Banner Image: President Duterte of the The Philippines. Picture: Getty Images