Politics & Society

Disinformation damages democracy, but perhaps not in the way you think

Australian politics tends to shy away from grand spectacle, but Albanese and Dutton both need to reassure a restless public that, amid global chaos, Australia remains anchored in pragmatism

Published 28 April 2025

Visit a factory floor, a suburban health centre, a construction site or a petrol station during this election season and chances are you’ll find a politician performing for the cameras.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, sleeves neatly rolled, holding up his Medicare card like a ticket to a better, fairer future.

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, stationed at a servo, hand on the bowser, pledging to cut fuel prices by 25 cents and to fix the nation’s energy woes through nuclear power.

These vignettes of political theatre feel routine. Predictable. Not because they’re particularly persuasive or effective, but because they follow a script we’ve seen so many times it barely registers.

Tightly scripted, light on drama, and rarely surprising – and for many, that predictability is a comfort. A national sigh of relief.

Australian politics tends to shy away from grand spectacle – Pauline Hanson’s theatrics notwithstanding – and we wear that restraint like a badge of honour.

No MAGA-style rallies, no chainsaws waved about to “cut waste”, no unhinged conspiracy broadcasts.

This political quietness is something we hold onto, as if moderation itself were proof that our democracy is sturdier, more stable, more mature.

Politics & Society

Disinformation damages democracy, but perhaps not in the way you think

This year, that instinct for restraint feels more acute than ever. Just six months after a tumultuous US election returned Donald Trump to the helm of the world’s most powerful nation, right-wing populism has rendered performative politics a toxic brand.

And yet, as theatre scholar Milija Gluhović notes in The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance, “all politics is performative”. Even when leaders appear to hold back, they are still performing – often more deliberately, working to sustain the illusion that they are not.

Australian politics might be quieter, but it is no less shaped by the same pressures gripping much of the West – a spiralling cost of living, housing insecurity, contentious debates over migration, climate anxiety and national security.

All set against a world growing more unstable, marked by radical shifts and a shrinking space for reason.

Both Albanese and Dutton have crafted their campaigns to reassure a restless public that, amid global chaos, they remain anchored in pragmatism – that Australia, under their watch, will not lose its grip.

Armed with his Medicare card, Albanese promises Australians they won’t need their credit cards at the doctor’s office.

He flips sausages at community barbecues, chats warmly with families and gently reassures us that things are improving – just not yet.

But in a country where out-of-pocket medical costs make people think twice about whether they can afford to see a doctor at all, that green card feels more like a gimmick than a guarantee.

His optimism is careful, almost subdued.

He is not selling “vibes” like Kamala Harris in the recent US presidential election, just steady hands and cautious hope. A man of the people, yet always at a measured distance.

Still, his government faces the steep challenge of talking about success and optimism at a time when many Australians are struggling to feel either.

Dutton’s stage is rougher, stripped back to the essentials.

He smiles from the back of a ute, pumps fuel and hopes that his promise to bring down energy costs will be enough to steady the ship.

It’s a blokey act – plain-speaking, no-nonsense. But for a man often seen as aloof, and carrying the heavy baggage of Scott Morrison’s legacy, his talk of nuclear power solving everything by 2040 feels like a gimmick too.

Yet Dutton has another shadow to contend with – the performance unfolding across the ocean, the long reach of Trumpism.

He has borrowed a few familiar lines.

“Are you better off now than three years ago?” he asks, echoing Reagan, echoing Trump. He pushed for a return to office work, only to quickly backtrack when the backlash hit.

And in a clumsy moment of machismo politics, he dismissed Albanese’s China response as “limp-wristed” – a slur with clear homophobic undertones.

The apology came fast, but the damage stayed. Dutton walks a tightrope. Lean too far into Trumpism, and he risks losing much of Australia. Step back, and he is left with few weapons at all.

What we’re left with is a slow battle of attrition, as each of the three leaders debates so far has made clear.

Albanese’s task seems relatively straightforward – let Dutton stumble, while holding steady as the calm, dependable moderate.

Dutton, meanwhile, is intent on casting Albanese as weak, borrowing the same tone Trump used to undermine Biden, though careful not to sound too much like Trump himself.

Politics & Society

What kids need to know about democracy in 2025

In the first debate – the Sky News People’s Forum on 8 April, held before 100 undecided voters in Western Sydney – both men stuck firmly to their strategies.

Albanese remained measured, offering up economic figures like falling inflation and job creation, while playing down the worst of the cost-of-living crisis.

His delivery was clean, well-rehearsed, confident but never showy, punctuated by the occasional nervous smile and an obvious effort to stay composed.

Dutton came in harder, dipping his toes into populism, thanking audience members for their sincerity in sharing their hardships and urging them to speak more.

He pushed fear, but never too far.

Assertive, but never desperate. He leaned on the familiar language of rationality and common sense – a Liberal playbook that has been in use for as long as I can remember.

Even the audience verdict was lukewarm: a narrow win for Albanese.

But no one left inspired, and no one left convinced that Australia’s declining quality of life would improve any time soon.

Then came the second debate, moderated by the ABC’s David Speers, set against polling showing Labor ahead.

Dutton had little choice but to push harder, take more risks and offer a vision – any vision. But in the end, the debate hinged on two moments, each powerful in its own way, though for very different reasons.

The Speers wasted little time in cutting to the core.

Early in the debate, he put it plainly: both leaders are property investors and neither was willing to touch negative gearing – a policy many see as central to Australia’s housing crisis.

The moment threw their prepared scripts into disarray.

Dutton mumbled something about “sensible reform” before sidestepping the question entirely.

Albanese initially dodged as well, before arguing that changes to negative gearing could shrink housing supply and push rents even higher.

It was a sobering reminder of just how closely aligned they are when it comes to protecting the status quo.

Later in the debate came its most powerful – and perhaps most overlooked – moment.

Speers presented stark data on rising Indigenous suicide rates and the growing number of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care, then asked why neither leader had visited an Indigenous community during the campaign.

The room shifted.

Dutton retreated into the past, noting he had visited before, as if that alone could settle the matter.

He avoided any confrontation with his party’s opposition to the Voice, a campaign many Indigenous leaders condemned as an effort to cement racism into the heart of national politics.

Albanese paused, visibly unsettled. He didn’t deflect.

Instead, he admitted his government’s failure to deliver on the promises of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

For a moment, the polished front he had carried through much of the campaign cracked. He said he was “heartbroken”, and for once, it rang true.

Business & Economics

Why Australians are made to vote

In that brief exchange, something real surfaced – a flash of remorse that cut through the usual choreography of political performance.

It was the moment that lingered, the one many may remember, a glimpse of why, despite their doubts, many Australians still want to believe in him.

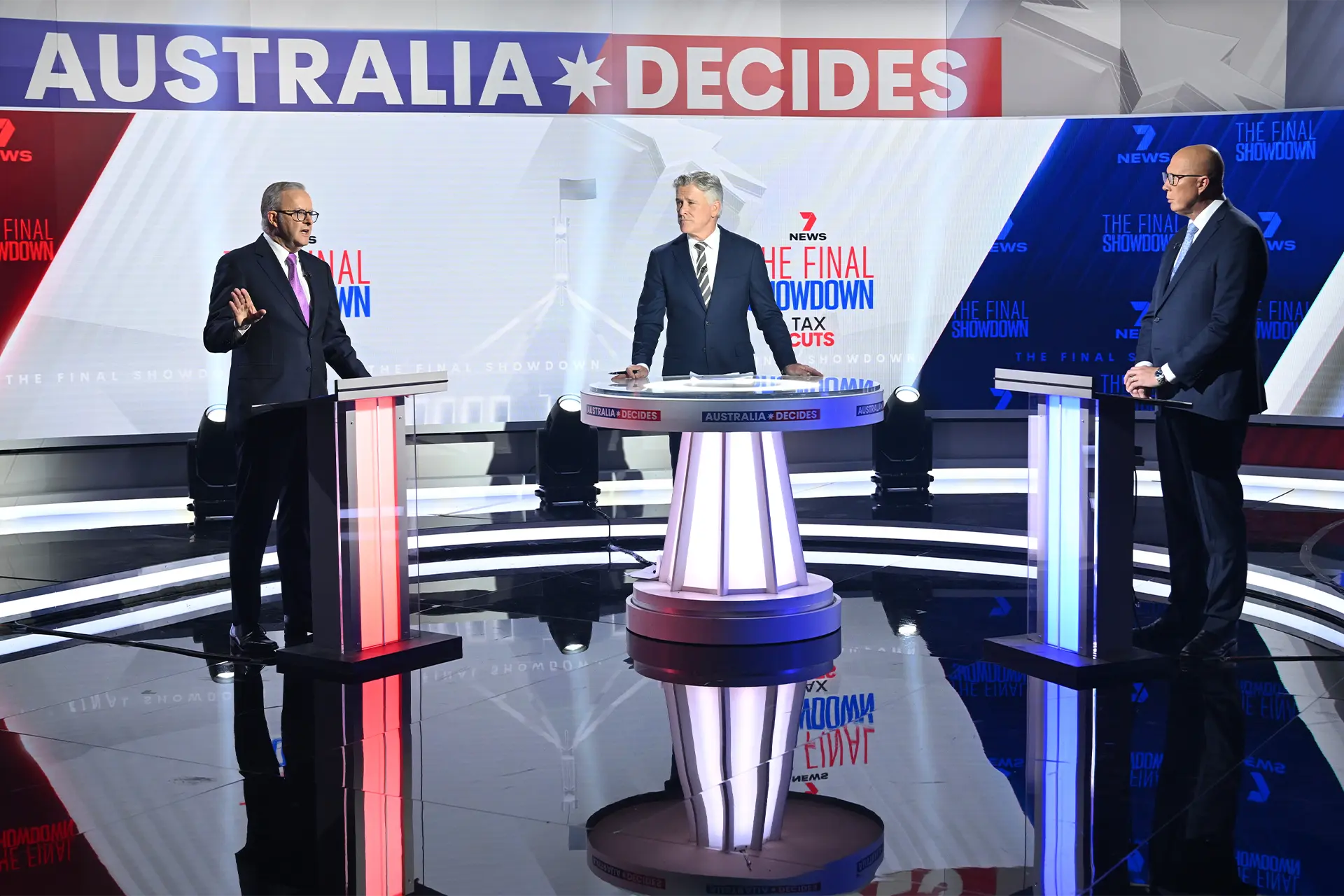

The final leaders’ debate of the 2025 federal election aired on Sunday, 27 April, from Seven’s studios in Sydney.

Chaired by 7NEWS political editor Mark Riley, it followed a deeply unsettling Anzac Day, where far-right extremists disrupted dawn services in Melbourne and Perth, heckling a Welcome to Country at Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance.

What unfolded was, without doubt, the most combustible and unpredictable debate of the campaign.

Dutton came out swinging, hurling a relentless barrage at Albanese’s record and credibility.

The tone was shaped not only by Dutton, but by Riley’s curious interjections – from asking Albanese whether he had Donald Trump’s phone number to flashing images of the Prime Minister’s sprawling holiday home before an electorate struggling to buy their first.

Still, Dutton’s grasp of the stagecraft of politics has always been shaky. His tightly managed image as a champion of the ordinary Aussie, a role he clung to throughout the campaign, came apart at the seams when he stumbled over a simple question: the price of a dozen eggs.

His hopelessly wrong answer didn’t just reveal how out of touch he really was; it laid bare the fragility of the persona he had worked so hard to sell, one that had never quite fit him. And in a debate of this magnitude, that kind of slip is hard to come back from.

The audience didn’t hold back – scorning Dutton’s performance and handing Albanese a clear win. Still, the verdict was hardly celebratory. Many in the studio remained undecided, a reminder of just how little this election has delivered in the way of real answers.

As James Carville, strategist for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign, famously put it:

It’s the economy, stupid!

Where their theatrics will ultimately land is still anyone’s guess.

If there’s one thing I’ve come to understand about political theatre through research, it’s that its power lies not just in the skill of the performers, or in any single dramatic moment, but in how well political actors attune themselves to the shifting mood of their audience.

On 3 May, we will see not only who played their part more skilfully, but also what Australians were willing to look past, as they weighed promises against reality, and performance against belief.