Health & Medicine

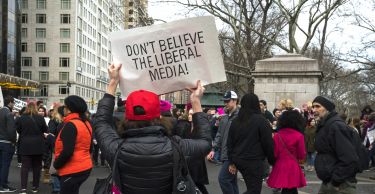

Sorting fact from fiction in a post-truth world

While the Internet provides a forum for democracy in some Southeast Asian countries, it’s also become a tool for fake news, misinformation and political hoaxes

Published 20 October 2019

In Southeast Asia, information manipulation has been increasingly used as an instrument to influence public behaviours, polarise societies, exacerbate ethnic conflicts, draw support of religious ideologies, manipulate election results and incite public fear, hatred and violence.

The 2019 election in the Philippines is a case in point.

The election featured deliberate obfuscation and lying along with trolling, fake accounts, impostor news brands, false news, misleading memes and microtargeting.

The flow of manipulated, fraudulent and menacing claims also affected the way that journalists produced news and how citizens engaged each other in rational and critical conversation about their way of democracy.

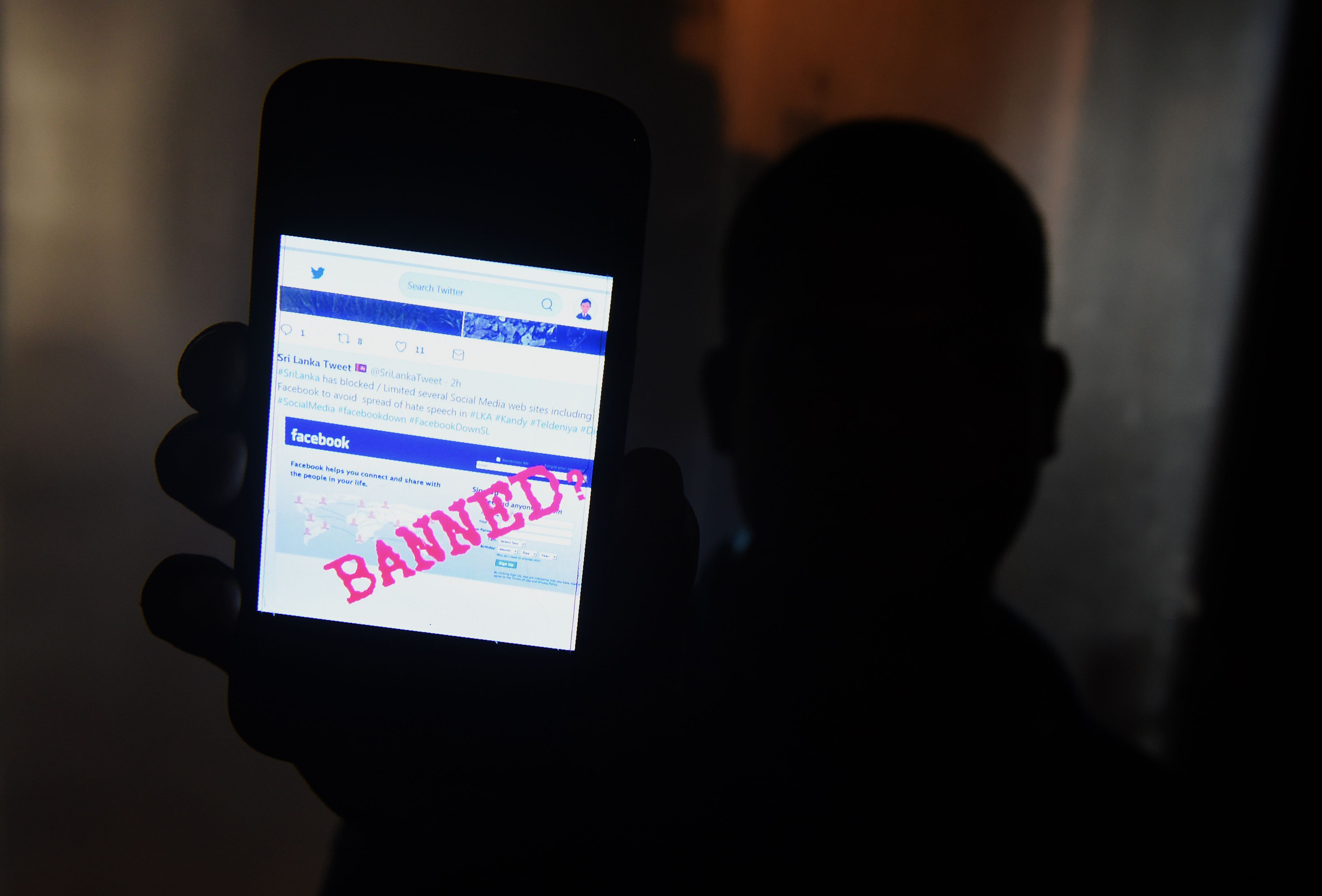

It became so obvious, that in the lead up to Election Day, Facebook invested significant resources to remove accounts and pages in violation of its policies.

Health & Medicine

Sorting fact from fiction in a post-truth world

This spread of misinformation is intensely bound-up with the elite-dominated politics that the presence of active fact-checkers cannot even stop the misinformation.

But, in the age of social media, factors like the easy production of user-generated contents, the anonymity of social media accounts, the rapid distribution of online information and the structure of the Internet make social media platforms a breeding ground of fake news.

Aside from revising or enacting new laws, governments, civil society groups, technology companies and private entities are still looking at fact-checking methods, media literacy programs and algorithm adjustments as possible solutions to fake news.

However, to date, these measures have largely been seen as ineffective and on many occasions infringe on freedom of expression.

For instance, Malaysia has scrapped a law making ‘fake news’ a crime, a year after an initial attempt to repeal the legislation was blocked by the opposition-controlled senate.

Just weeks before the government of former Prime Minister Najib Razak lost the 2018 election, the Anti-Fake News Act 2018 was passed by in a move critics said was designed to stifle dissent.

Arts & Culture

Why fake news is anything but new

According to 2019’s global digital report, We Are Social, 2.2 billion people in East, Southeast and South Asia use the Internet with penetration rates at 60 per cent, 63 per cent and 42 per cent respectively. Social media use by those aged 13 years or above sits at around 82 per cent in East Asia and 78 per cent in Southeast Asia.

Awakening minds to minimise meme hoaxes and stop their spread without relying fully upon authorities, is the responsibility of the community.

Still, implementing law enforcement that is fair and strict towards perpetrators of hoaxes, especially the makers and spreaders, remains a responsibility for the government.

But, regulations alone will not resolve the hugely inflamed hoax problem in society.

So, consistency from legal structures is required to enforce the law in cracking down on hoaxes and smear campaigns, as well as a strong legal and political culture among people to see through fake news.

Political memes inciting conflict through issues like religion, culture, and race must be fought with a strong political culture and a stronger sense of unity through the diverse societies of countries like Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.

Arts & Culture

Why documentaries matter in an era of fake news

FACT vs FAKE

The line between fake and fact in politics remains opaque as most ‘fake news’ contains some truth, some speculation and some liberal interpretation.

There is also downside to policing ‘fake news’ with some governments seizing on the opportunity to introduce censorship or political control.

However, controlling ‘truth’ is a means to controlling news and political communication, and neither aids the democratic process.

In order to better understand contemporary threats like misinformation, disinformation and malinformation, it is fundamental to give priority to the local context in which the digital and political transformation is happening.

We cannot know the extent to which fake news constitutes a problem if we don’t link it to socioeconomic factors like education or digital literacy.

So, any action must be tailored to the needs, views and opinions of the local community.

In other words, it shouldn’t be assumed that the western conceptualisation of democracy will necessarily work in Southeast Asian countries.

Arts & Culture

Defining the power of public interest journalism

Countering disinformation doesn’t necessarily entail the infringement of people’s rights and freedoms.

Extraordinary and assertive countermeasures and strict legislation don’t guarantee a successful and effective response to disinformation campaigns.

On the contrary, empowerment through enhancing media literacy and outreach to debunk disinformation and de-marginalisation are more legitimate and effective strategies for combatting disinformation.

Many Southeast Asian countries are realising that regulation for cyberspace is important.

The Indonesian government is in its so-called Access Controlled phase – a large series of mechanisms, at a variety of points of control, that can be used to limit access to knowledge and information.

Meanwhile, Singapore has introduced a law against fake news which rights’ groups warn may stifle free speech, and opposition politicians say could give the government too much power as elections loom.

The Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act was passed in May after just two days of debate in a legislature heavily dominated by the ruling party in Singapore. The law stipulates that any government minister has the prerogative to decide what constitutes a “false statement of fact”.

Politics & Society

Bringing democracy to the internet

Over the last decade, digital democracy has allowed citizens in Southeast Asian countries to benefit from the participatory features of the Internet, a tool that can potentially disrupt the political scene by widening the concept of political participation.

In Malaysia, mainstream media has for decades been controlled by strict laws, as well as self-censorship by print and broadcast journalists and editors. But now the country is seeing an exponential growth in independent news portals and alternative news sources.

My research found that these sources have had the effect of broadening the variety of topics reported, increasing informed participation in political culture and presenting political alternatives.

This kind of democratisation of information has the potential to encourage new forms of democratic participation and have a significant impact on political culture in the country.

This is due to the inclusive nature of digital tools that empower stakeholders, thereby generating new ways of political participation.

In Cambodia, this is especially true after a large amount of power was concentrated in the hands of the ruling political elites, leaving the majority of people at the margin of politics.

Politics & Society

How the toxic went mainstream

However, following the 2013 elections, the widespread use of Internet-based tools quickly vanished and was replaced by a generalised sense of political fear and self-censorship on the net.

There is little doubt that the problems associated with the positive use of digital tools, like fake news, will persist.

Civil society is quickly catching up with the new uses of digital democracy, but it is the elites who quickly become tech-savvy, counterbalancing the push of the people.

Digital democracy lives through individual use of online media and the Internet, but uncontrolled digital democracy could undermine the quality of democracy itself.

Banner: Getty Images