Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

Although the Australian government rejected the recommendations of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, saying Australians would not support a First Nations voice to Parliament, experts say there are still reasons to hope

Published 19 July 2018

Nine months after the Prime Minister’s rejection of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, I remain hopeful constitutional recognition can still be achieved.

The Uluru Statement created a massive political opportunity that is not going away. The opportunity remains alive and growing – waiting for smart political leaders with the moral courage, strategic intelligence and vision to seize it. Those who seize it will make history.

This is a proposal – the only proposal – that can win a recognition referendum.

I’m optimistic because public support for a First Nations constitutional voice continues to grow, despite the government’s rejection. Polling shows around 60 per cent of Australians support a First Nations voice in the Constitution – even in the face of government opposition.

For context, around 60 per cent of Australians supported marriage equality in the same sex marriage survey, with the Prime Minister arguing for the change. In Indigenous recognition, he argued against a First Nations voice, yet it still polls at around 60 per cent.

Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

The Uluru Statement still represents the best chance the country has ever had, and will ever have, at meaningfully reforming the constitutional relationship between Indigenous peoples and the colonising state. Some of the hardest pre-requisites have already been met.

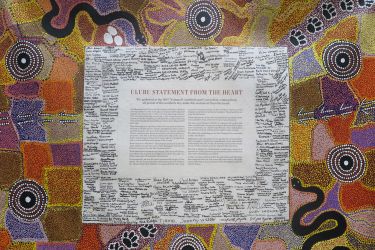

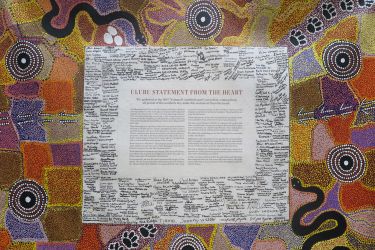

Most importantly, the proposal has garnered Indigenous support. In May 2017, Indigenous Australians formed an unprecedented national consensus on the constitutional reform they want: a constitutionally guaranteed First Nations voice in their affairs. This consensus was unprecedented.

Equally extraordinary was the fact that their consensus position was sensible and pragmatic. A constitutionally guaranteed voice has attracted the support of key constitutional conservatives because it is a legally moderate reform, described by Vice-Chancellor and President of Australian Catholic University Professor Greg Craven as “modest yet profound”.

The proposal is specifically designed to uphold the Constitution, respect parliamentary supremacy and eliminate legal uncertainty, while constitutionally empowering Indigenous people with a voice in their affairs.

It proposes no veto; just a voice – something Indigenous leaders have been advocating for decades.

Since William Cooper’s letter to King George in 1937 calling for Indigenous representation in Parliament, the Yirrkala bark petitions in 1963 calling for fairer consultation in decisions made about their land, and the Barunga Statement in 1988 calling for an Indigenous representative body to oversee Indigenous affairs, along with a treaty – Indigenous advocates have never stopped asking for an empowered voice in their affairs.

Here was the Prime Minister’s massive missed opportunity, arguably the biggest in his prime-ministership: a never-before-seen Indigenous national consensus on the same constitutional reform proposal that key constitutional conservatives are advocating.

Politics & Society

A Constitution shaped by distance

When before have staunch constitutional conservatives like Liberal MP Julian Leeser (the current co-chair of the Joint Select Committee, who successfully opposed a republic, opposed a bill of rights, and opposed the push for a local government referendum), Professor Greg Craven and writer, lawyer and philosopher Damien Freeman, supported the same substantive constitutional reform that Indigenous people are seeking? Never, as far as I’m aware.

Yet after the Uluru Statement, these two groups are united in agreement on the merits of a constitutional voice as both empowering and constitutionally safe.

When before in history have right-wing advocates like radio host Alan Jones, former Liberal Premier Jeff Kennett, and journalist Chris Kenny been in furious agreement with progressives like author Thomas Keneally, former Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, lawyer Julian Burnside, along with Labor and the Greens, who have all said they support the reforms called for in the Uluru Statement?

Not to mention the strangely encouraging phenomenon of Labor Shadow Treasurer, Chris Bowen, publicly congratulating his natural right-wing rivals, constitutional conservatives, for their support of the Uluru Statement.

The Uluru Statement’s call for a voice can unite black and white, and left and right.

As I explain in my new book, Radical Heart, the Prime Minister rejected the Uluru Statement because he preferred a merely symbolic constitutional amendment – he let this slip to the Referendum Council before the dialogues on options even began. At a meeting in November 2016, the Prime Minister said a constitutional voice had a “snowflake’s chance in hell”, and outlined his preferred model: constitutional minimalism.

Politics & Society

From the margins to the mainstream

But constitutional minimalism failed in 1999 when former Prime Minister John Howard pushed a symbolic preamble. It cannot succeed today. It would be opposed by the majority of Indigenous people, who have repeatedly made clear that they seek substantive constitutional reform, and that they would say no to minimalism.

Constitutional conservatives will also galvanise against the insertion of flowery statements, to uphold the Constitution and prevent uncertain judicial interpretation of ambiguous symbolic words.

Indigenous advocates in favour of substantive constitutional reform over empty symbolism will find unexpected allies in constitutional conservatives: together they will form a powerful coalition that would defeat a minimalist referendum.

With a First Nations’ constitutional voice, however, these two groups unite as passionate advocates for sensible yet substantive reform.

Such an alliance may yet play out as reality.

A Joint Select Committee has been appointed to further Indigenous constitutional recognition. Due to public pressure, the Uluru Statement is part of its terms of reference, indicating the Prime Minister’s rejection is not the last word.

The Committee’s co-chairs are Patrick Dodson, the father of reconciliation, and constitutional conservative Julian Leeser, a co-designer of the constitutional voice proposal. The vast majority of public submissions support the Uluru Statement.

The opportunity to realise a historic resolution on constitutional recognition now looms in the federal parliament.

It’s now up to all Australians to hold the politicians to account and back the Uluru Statement. If we the people make our voices heard, government will no longer be able to deny the voice of the First Nations.

Dr Shireen Morris is a McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow at Melbourne University Law School and a Senior Adviser to Cape York Institute. She is the co-editor of The Forgotten People (MUP) and A Rightful Place(Black Inc). Her new book, Radical Heart, will be launched on Monday 23 July. Register here: https://events.unimelb.edu.au/events/10742-radical-heart

Banner image: Fairfax Media