Health & Medicine

How do young Australians see violence against women?

It should be exciting to say that cases of violence against women dropped during COVID, but we need to understand the big picture

Published 15 March 2023

In Australia, women are three times more likely to experience intimate partner violence (IPV) – physical and/or sexual – in their lifetime. It stands at 23 per cent compared with 7.3 per cent of men.

In fact, women are four times more likely to experience this violence in a dating relationship (9.3 per cent of women and 2.3 per cent of men).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, with lockdowns and other limits on social gatherings, many expressed concerns these restrictions would lead to the escalation of domestic and family violence.

The United Nations Secretary-General called it a “shadow pandemic” and urged governments to prioritise the prevention of violence against women in their national response for COVID-19.

But as the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) releases thefourth wave of its Australian Personal Safety Survey (PSS) – a complex picture emerges complicated further by the COVID limitations on the research itself.

Health & Medicine

How do young Australians see violence against women?

The survey has found that, here in Australia, the number of women experiencing intimate partner violence dropped during the pandemic, but how does this compare with expectations of an increase in IPV during the pandemic?

The Australian Personal Safety Survey collects information from men and women aged 18 years and over about the nature and extent of violence experienced since the age of 15.

This includes specific experiences of IPV which the World Health Organization defines as “any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship”.

An intimate partner can include a current partner you live with, previous partner you have lived with, a boyfriend, girlfriend or date, or an ex-boyfriend or ex-girlfriend you’ve never lived with.

The reality is that IPV has been and continues to be primarily perpetrated by men towards female partners.

If we look only at cohabiting partner violence, women are three times more likely than men to have experienced physical and/or sexual violence, twice as likely to experience economic abuse and one and a half times more likely to experience emotional abuse.

Health & Medicine

Making the link between family violence and animal abuse

Despite this, one in three Australians believe that women and men perpetrate partner violence equally.

Since 2010, Australia has invested in a National Plan to reduce and end violence against women and girls using the PSS as a key monitoring tool. To measure changes in the prevalence of violence over time, we need to look at the experience of violence during a particular time period.

Partner violence is usually measured by asking about a person’s experiences over the last 12 months.

So, in this survey, which was conducted in 2021-2022, respondents were asked if they had experienced different forms of violence from an intimate partner in the last 12 months – so that’s between 2020 and 2021.

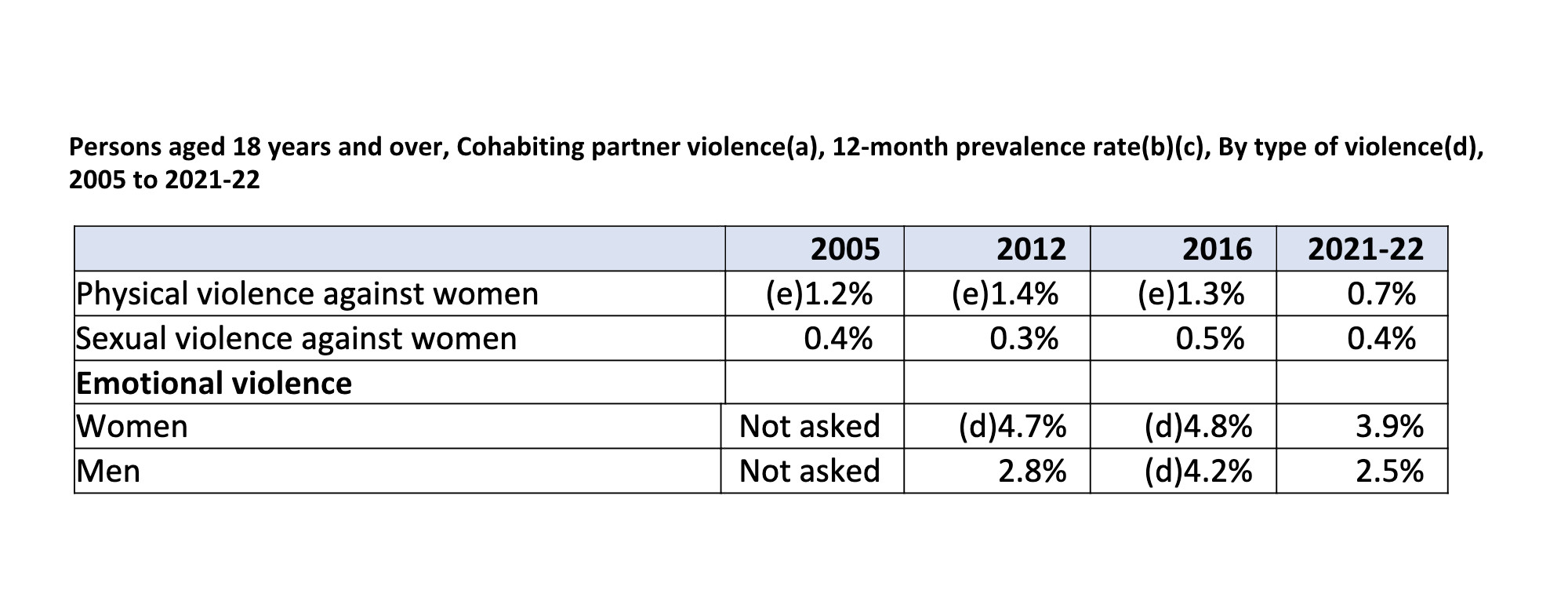

These same questions were asked in the 2005, 2012, 2016 and 2021-22 surveys.

In 2021-2022 – while COVID lockdowns continued – there was a significant decrease in 12-month partner violence. It dropped from 2.3 per cent in the 12 months prior to the survey in 2016 to 1.5 per cent during 2021-2022.

Health & Medicine

Making every woman count

The patterns for cohabiting partners also showed a significant drop in physical violence and emotional violence from 2016 to 2021-2022.

This overall pattern of decreased cohabiting violence also occurred in Victoria, Queensland and South Australia, while emotional violence decreased in the Australian Capital Territory. Rates were unchanged in New South Wales, Western Australia, Tasmania, and the Northern Territory.

This data can also be interpreted within the context where overall rates of physical violence against both women and men have been in decline since 2005, and the rate of sexual violence remains unchanged.

Similarly, the ABS crime victimisation survey (which collects the experiences of individuals and households of selected crimes, whether or not they reported it to police) showed a notable decrease in reported rates of physical assault by an intimate partner in the 12 months prior to the 2022 survey.

This dropped from 30.8 per cent of females surveyed in 2020-2021 to 15 per cent in 2021-2022. Among men, the rate decreased from 6.9 per cent to 4.9 per cent.

While it should be exciting to report a reduction in partner violence – particularly due to the effort and national funding put toward reducing violence against women and children – these results are confounding due to the circumstances in which the survey was conducted.

Health & Medicine

The isolation of domestic violence

The 2021-2022 survey was conducted during a time of pandemic lockdowns and social isolation with unknown impacts making this change hard to interpret.

These impacts range from some women living in confinement with violent partners and other women locked down separately from their abusive partners, some women able to seek violence support from specialists, police and other services, while others were more isolated.

On top of this, the ability to conduct survey interviews was disrupted.

Globally, it was expected that the pandemic itself and the responses to it would exacerbate risks and triggers for IPV.

This includes stressors we already know play a part in triggering violence – like increased unemployment and financial strain, social and geographic isolation, lack of support for illness and metal health disorders, as well as increased alcohol consumption at home.

The way we lived during the peak of the pandemic also reduced protective factors like social connectedness, freedom of movement and informal social control.

As a result of all of these factors, there was growing concern for women living through pandemic lockdowns with abusive partners as well as ensuring that incidences of IPV were accurately recorded during this time.

In an attempt to monitor IPV in real time, various models of research accommodating the pandemic restrictions show mixed results.

Health & Medicine

No place for ‘good bloke’ excuse

In some countries, increased calls to domestic violence helplines were recorded, while in other areas, survivors of violence only had access to limited information and awareness about available services.

However, an over-riding concern was that women locked down with an abusive partner would be unable to find privacy to reach out for support.

In Australia, the Australian Institute for Criminology conducted an online panel survey with 10,000 Australian women during the first 12 months of the pandemic.

These results indicated that the pandemic coincided with first-time and escalating violence for a significant proportion of women and many women attributed these changes to factors linked with the pandemic.

In Europe, a study across 10 countries during the first two weeks of the pandemic showed an increase of IPV reports in six countries, a decrease in two and unchanged reports in another two countries. A rapid systematic review returned mixed results of studies showing increases and decreases of IPV in police and hospital records globally.

As national prevalence studies that were disrupted by the global pandemic are being published, we are seeing some consistent trends. This includes either unchanged rates of IPV or a reduction in prevalence of IPV – like we’re seeing in the new Australian data.

Health & Medicine

Stopping sexual assault means addressing violence in relationships

The New Zealand Violence Against Women prevalence survey shows a significant decrease in overall IPV and current partner violence during the pandemic. The US Crime Victimization survey also shows a decrease of IPV from 2.5 per cent in 2019 to 1.7 per cent in 2020.

A single state prevalence survey in the US state of in Michigan shows unchanged rates of prevalence in the three months immediately pre-pandemic compared with three months during the pandemic lockdown. Similarly, the Crime Survey for England and Wales showed unchanged prevalence rates.

So, what does this tell us?

The current PSS results show an overall decline in physical violence for both women and men, both partner related and non-partner – so it might be that Australia’s national policies and programs are having an impact which became evident during the pandemic.

However, the context of the pandemic and review of other research results globally do add a layer of complexity to the interpretation.

While some research identified new or novel cases of IPV during the pandemic, as well as increased reporting, help-seeking and severity of IPV, national prevalence measures are not showing the same consistency.

We do not know definitively why these results are different, but we can propose some sensible theories which may fuel further important research.

Health & Medicine

Listening to the voices of survivors of violence and abuse

Firstly, the research methodologies during the pandemic varied considerably – some were telephone or online video interviews, others were self-completion surveys. While each research method may be valid in itself, they cannot be compared with actual national prevalence measures. These differing approaches can make it hard to compare data collected during the pandemic.

Secondly, the local conditions of the pandemic and lockdowns also varied considerably – not just here in Australia, but globally.

This has had an unknown impact on either triggering or suppressing violence, survivors seeking help and the available response from support services, some of which innovated to respond in novel ways.

Thirdly, it might be that there was some positive impact from the pandemic. Some families formed a solidarity or cohesive connectedness against the uncontrollable crisis of the pandemic – pulling them together rather than fragmenting apart.

Having national policies supporting income and loss of employment may have also helped to alleviate some of the typical triggers for violence.

Finally, everyone’s experience during the pandemic was different – some people had more access to income support, others lost businesses, some lived with their partners, others lived apart – so the lived inconsistency is reflected in the data.

What these survey results do tell us is that the investment Australia has made into reducing IPV may be paying off. While this is good news, we may not be seeing the whole picture.

Banner: Getty Images