The Voice to Parliament and echoes of Mabo

Australians vote this year in a referendum that could enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, alongside State and region-based Treaties, Truth-Telling and State based-Voices to Parliament

Published 6 July 2023

During NAIDOC week 2023, many in our community are braced for the challenges of the next few months as we draw near to a referendum on the question of whether there should be a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament.

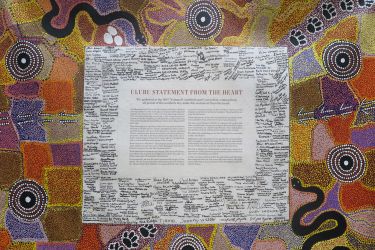

In the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the First Nations Voice sits alongside the establishment of a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and Truth-Telling about our history.

As a young doctor, I was introduced to the National Aboriginal Health Strategy developed by Aboriginal health leaders. The Strategy made the connection between land and health, and demonstrated that health is not just the absence of disease but is grounded in the spiritual cyclical life, death, life connection we as First Australian’s have to our lands.

I am grateful that here in Victoria, processes for Treaty and Truth Telling are happening alongside the National referendum process to decide whether to establish a First Nations Voice to Parliament in the constitution.

To understand the significance of the referendum, it’s important to understand complex ideas about law, place, custom, language, spiritual belief, cultural practice, sustenance, family and identity.

And, historically, it’s been a long road to travel to get to this point.

Family connection to land

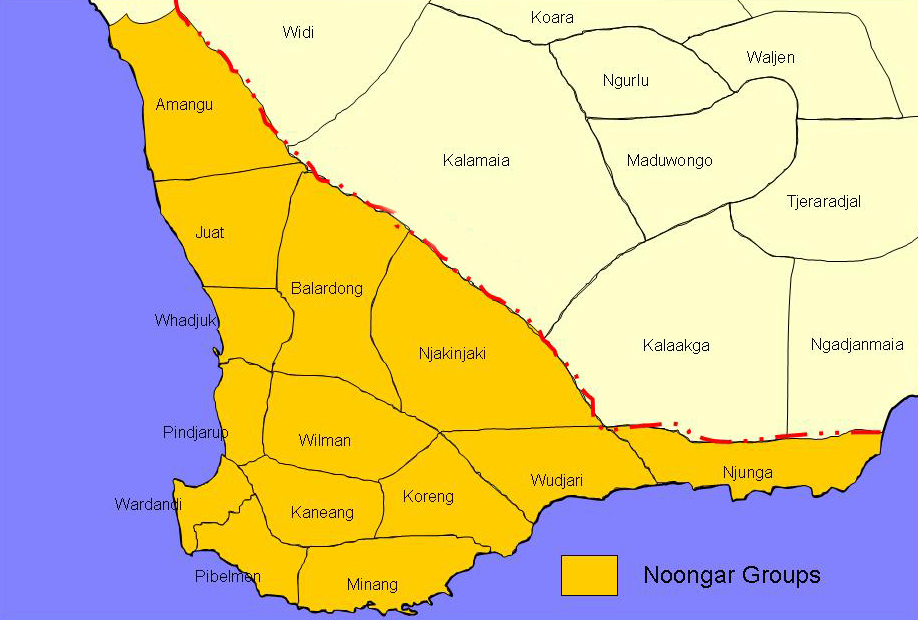

The proposed changes in Victoria, nationally and in my home with the Noongar nation in the southwest of West Australia were almost unimagined when I was born in 1967.

As my birth certificate shows, at the time of my birth I went home to live on the Mount Barker Native reserve with racial segregation thriving in that small rural town.

The successful 1967 referendum had not yet been run and there were no efforts to let Noongar people live inside the town among the rest of the community.

The history of Aboriginal control and management of their ancestral lands is not ancient history.

I knew my grandmother, Muriel, growing up in the 1970s and it was her grandmother and great uncle who dealt directly with the Federation and the marginalisation of Aboriginal people on their own lands.

My maternal grandmother Muriel ‘Yuajangan’ born in 1906 was the daughter of Minnie Knapp and the granddaughter of Jackbam a well-known Mengang Noongar woman from the Kalgan River region of Albany.

Federation 1901 records that Jackbam, ‘Jackbone alias Polly’, was one of ten Aborigines of full descent living in Albany. The others include her half-brother, Tommy King, and her third husband, Dickie Bumble.

I am also related to Jackbam’s half-brother, Tommy King, or Wandinyilmernong, who was an important Noongar leader in the Albany region.

In October 1890, the Governor of Western Australia, Sir William Robinson, arrived in Albany to lead celebrations associated with the granting of self-government to the colony.

During the afternoon, Tommy King – the “boss Aboriginal” – accompanied by several others in war paint, presented him with a petition.

King’s petition claimed that Albany belonged to his ‘tribe’ and that it had been stolen by agents of the British Crown. Not only had the land been taken, but also the Aboriginal people had been deprived of their means of living and their dignity.

King clearly asks for compensation for his lost land.

Sciences & Technology

Our Country, Our way

My paternal great grandfather, Eddie ‘Womber’ ‘King George Williams’, was born in 1874 on Wudjari country. He married Toolyanne who was also born on Wudjari country and she later took on the name Lilly Burchill. They named their son, my grandfather, Ivan Williams ‘Gnoomer’.

‘Womber,’ was the son of Scottish settler George Cheyne Moir and an Aboriginal woman called Kalbiyart.

Eddie Womber Williams’ family recorded that Noongar names have a specific meaning. ‘Womber means ‘fire ablaze at night-time when it’s calm; the fire makes that noise, womber, womber.’

My grandparents ‘Gnoomer and ‘Yuajangan’ married on the Gnowangerup mission in the early 1900s and that was where their daughter, my mother, Gwen was born in 1938.

My father Stafford, the son of Sydney Eades and Ella Krakouer, has a similar Noongar family history.

The impact of native title

On 3 June 1992, in the Mabo land rights’ case, six of the seven High Court judges upheld the native title claim by the Meriam people that they were “entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands” and ruled that the lands of this continent were not terra nullius or “land belonging to no-one” when European settlement occurred.

The High Court’s Mabo judgement paved the way for the 2006 Federal Court judgement by Justice Wilcox which upheld the Indigenous Noongar people’s claim on more than 6,000 square kilometres of land in and around Perth.

Politics & Society

Don’t twist the aim of The Voice for political gain

The Court acknowledged the impact of European settlement on that system of laws and customs but decided that the effects of settlement had not destroyed the continuity of Noongar society and that its existence today is sufficiently founded in the traditional laws and customs which existed at sovereignty.

The recognition of Noongar native title was the basis for what some legal experts say is Australia’s first Treaty with Indigenous Australians.

While the initial Wilcox judgement in the Federal court was overturned at appeal, the Noongar people and the Government of Western Australia negotiated a Settlement to end the Native Title dispute rather than pursue further costly and prolonged legal contests.

The settlement or Treaty has wide-ranging benefits for Noongar people with an estimated value of $A1.3 billion including the establishment of a future fund, the return of certain Crown lands, joint management of national parks and the preservation of Noongar Heritage sites.

The Truth-Telling emphasised in the Uluru Statement from the Heart means we need to hear stories like mine from families around Victoria and around Australia.

We have a very colonised view of our histories shaping our beliefs about the need for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament and other national and State based measures to repair our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

Some people also wrongly believe that while we are acting to advance the Voice to Parliament, nothing is being done to advance Treaties and Truth-Telling.

Honouring indigenous cultural heritage

The ancient histories of Indigenous people should be treasured in the national story.

Tragedies like the destruction of the Jukan Gorge by Rio Tinto should never be repeated. In the Noongar Treaty and, I believe in the Victorian Treaties, preservation and protection of heritage sites and practices is paramount.

I am hopeful that Australia will vote ‘Yes’ in the coming national referendum to establish a First Nations Voice to Parliament.

I also look forward to witnessing the first Victorian state-wide Treaty and further regional Treaties over the coming years.

This is an edited extract from Professor Eades’ Halford Oration which commemorates the first Dean of Medicine at the University of Melbourne.

Banner: