Health & Medicine

Brush your teeth! It could save your life

New technology offers a way to visually examine the mouth for cancer, without the need for a surgical biopsy

Published 26 July 2020

If you noticed a new dark spot on your shoulder or changes in an old mole – you would know to get it checked out.

But would you know if you had a skin cancer in your mouth?

As our population ages, the diagnosis of oral cancer is increasing. Globally, this devastating cancer affects 750,000 people and has a five-year mortality rate of approximately 50 per cent if not detected and treated early.

The insidious nature of oral cancer means it is often detected at a later stage; up to half of people who are diagnosed with oral cancer have large tumours as oral cancer is often painless and unseen.

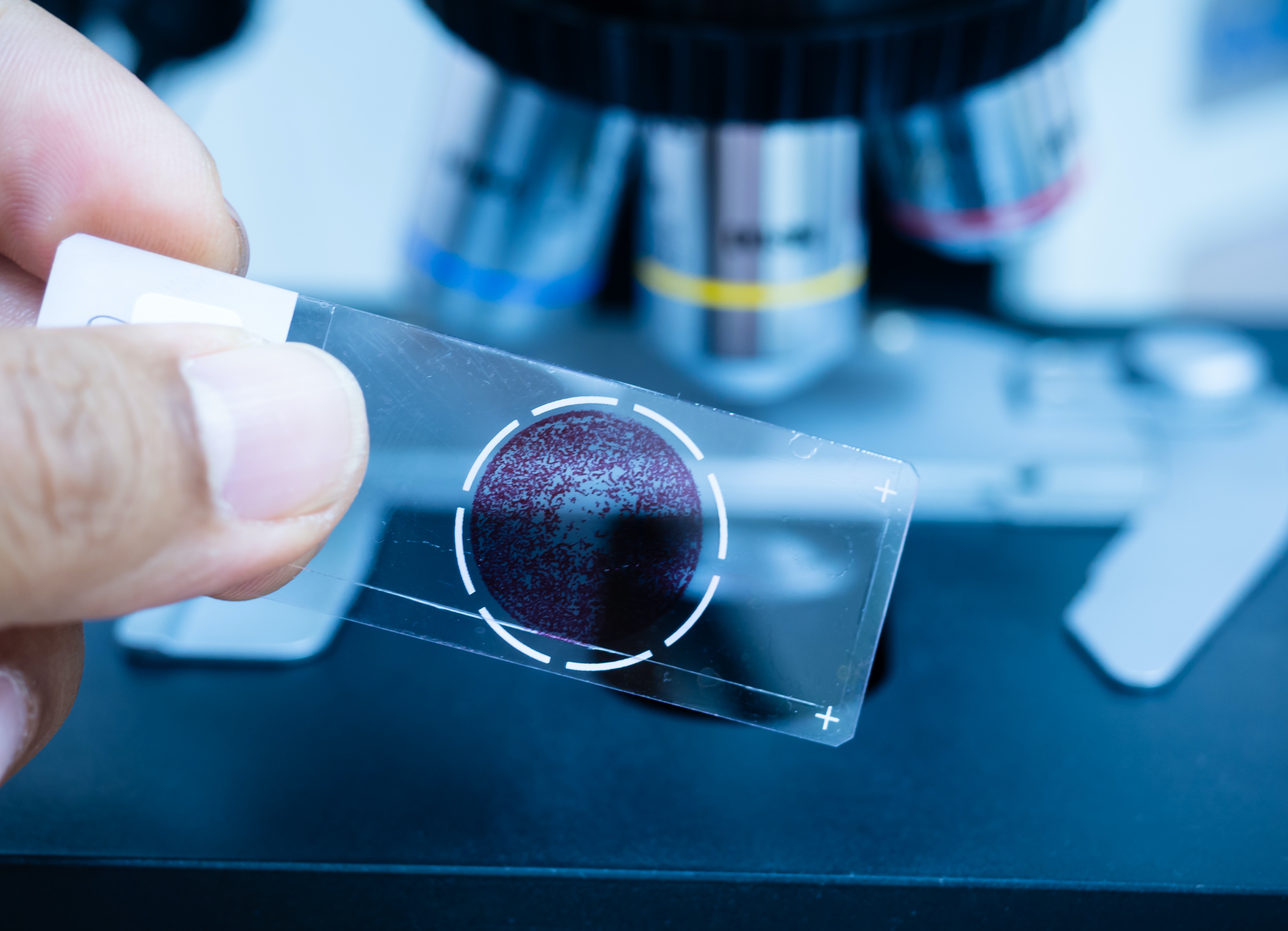

A further challenge is the limited tools to detect and monitor potential oral cancers and skin lesions over time; this forces clinicians to remove suspicious lesions by scalpel biopsy and assess pathology.

A new research project aims to identify individuals who are likely to develop oral cancer, without invasive biopsies.

The Melbourne University Dental School has partnered with Victorian company OptiScan, to improve screening and early diagnosis of oral cancer.

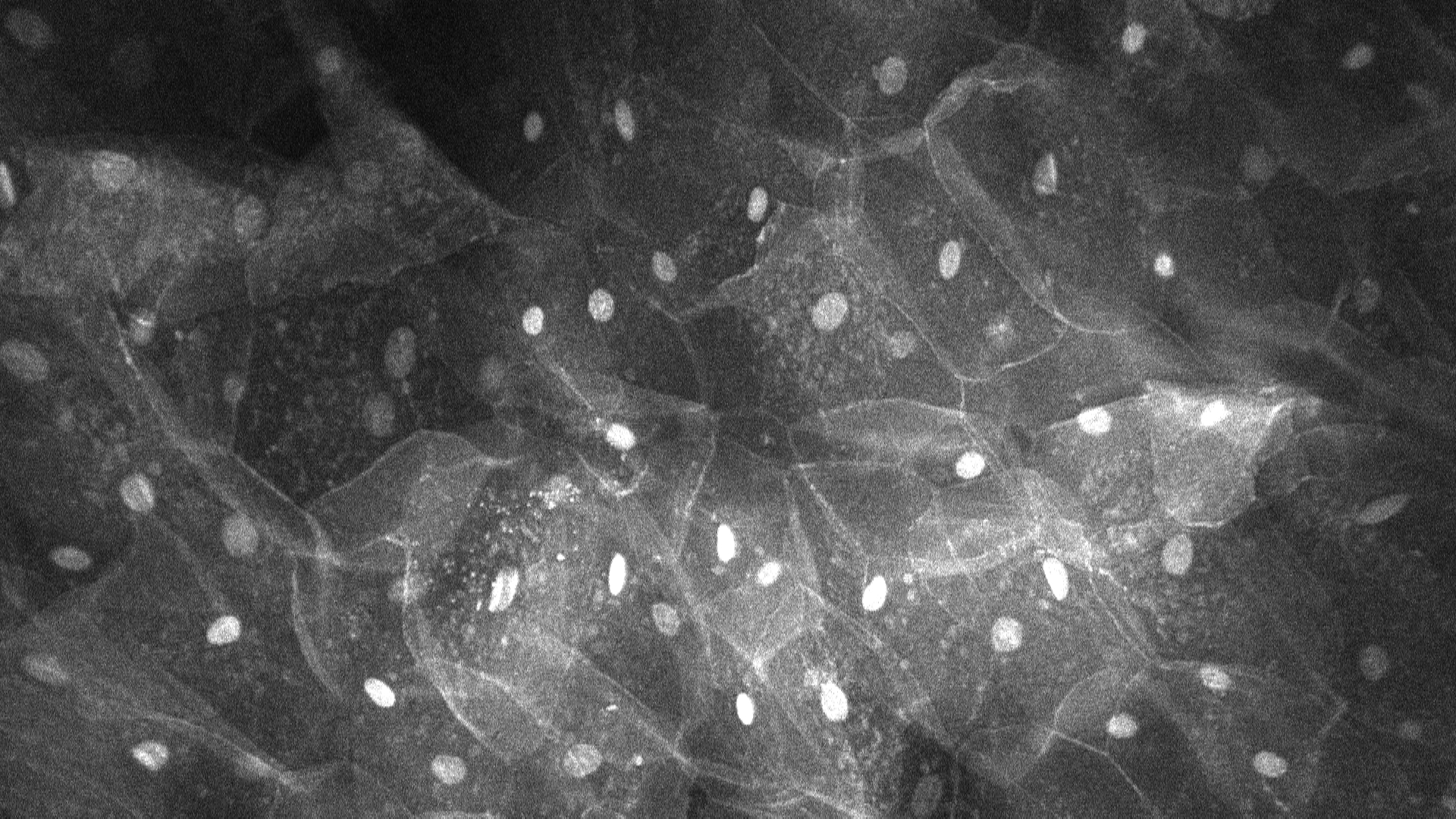

The project is led by our team at the Melbourne Dental School and uses Optiscan’s state-of-the-art confocal laser endomicroscope (CLE). Known as InVivage ™, the hand-held microscope uses a laser light and confocal optics to painlessly perform “digital biopsies”.

Oral cancer can have a devastating impact on a person’s life – removing a cancer from the mouth and tongue can impact on a person’s speech, their ability to swallow and eat, and ultimately, their self-esteem.

What we want to ascertain through our trial is how we can use OptiScan’s technology to microscopically see tumour cells in our clinic, helping us to assess the tissue and determine if a biopsy or surgery is required there and then.

Although 95 per cent of the lesions we see are not cancerous, without a biopsy, which can be painful and invasive, it’s very difficult to determine which lesions are cancerous or not.

The earlier the diagnosis can be made, and the least tissue we can remove – the better for the patient.

Health & Medicine

Brush your teeth! It could save your life

Oral cancers are often preceded by changes in the appearance, such as the colour and thickness of the skin of the mouth. These changes are considered to have the potential to grow an oral cancer and affect as many as one in 20 people.

However, only around three to five per cent of people with these changes will develop an oral cancer.

Once a biopsy sample is taken, it’s is assessed by a pathologist to see if there is any cancer present.

Sometimes there are changes in the way the skin is growing, called dysplasia, which tells us there may be an increased risk of cancer developing in the future. Still, this assessment is a limited predictor and can only be made on the small piece of skin that has been sampled.

With the hand-held confocal laser endomicroscope (CLE), tissue can be viewed in 3D with 1,000-times magnification.

This could allow clinicians and surgeons to diagnose cancerous tissue in real time, reducing or eliminating the need to have one or more biopsies taken and sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Alongside trialing the CLE, our project also aims to develop software to comprehensively record an annotated map of the patient’s mouth with Optiscan as well as our other project partner, MoleMap.

Health & Medicine

Are you taking care of the microbes in your mouth?

This means we could compare a patient’s mouth map the next time that they come in, to assess any changes.

We can also use special dyes that show us all the cells in the skin surface or another that only binds to molecules that are found more commonly in cancer, identifying potential ‘hot spots’ of skin growth.

Our broader Mouthmap™ project will enable a detailed collection of a large amount data to compare this new CLE technology to diagnosis using standard light microscopy; this has the potential to establish a new standard of diagnosis and allow advancement of both human and computer algorithm-based learning.

Our research aims to provide a solid foundation to advance towards clinical trials and recommendations to changes in standard of care.

The participants in this clinical study will be recruited by invitation from our main oral pre-cancer referral centre, networked with regional community centres where only individuals on healthcare card and pension card holders are eligible for treatment.

This is important because lower socioeconomic status ,as well as older age, are both considered risk factors for oral cancer.

Our goal is that this technology will help to reduce the need for scalpel biopsy in the future, allowing for more comprehensive assessment of skin changes in the mouth and earlier detection of oral cancer.

The Melbourne Dental School trial is due to commence in September this year, by referral.

The Melbourne University Dental School has partnered with OptiScan, a Victorian company, awarded a grant of almost $1 million by the Australian Government through the Medical Research Future Fund in collaborative clinical research project to improve screening and early diagnosis of oral cancer. This project was one of 21 national project funded in 2020 through the BioMedTech Horizons Program and administered by MTPConnect.

Banner: Shutterstock