Trial by Ouija Board: When jurors misbehave

In his new book, Professor Jeremy Gans explores a famous case of juror misconduct from the 1990s, and its ongoing implications for the trial-by-jury system

Published 3 October 2017

The limits of jury trials were famously exposed in the 1994 English case of Stephen Young, who was accused of murdering husband and wife Harry and Nicola Fuller. Four jurors consulted a makeshift Ouija Board while staying overnight in a hotel, ultimately leading to a retrial.

The incident, often referred to as the ‘Ouija Board Jurors’, is seen by many as the nadir of reported juror misbehaviour in the 20th Century.

The following is an edited extract from University of Melbourne Professor Jeremy Gans’ book, ‘The Ouija Board Jurors: Mystery, Mischief and Misery in the Jury System’.

Increasing awareness of juror stress

The first half of the 1990s marked a new awareness of the stress some jurors experience.

In the USA, this recognition arose in 1992 after the trial of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, where the evidence was so graphic that the judge arranged for mental health professionals to offer a post-verdict debriefing to the jurors; all 14 accepted.

Two years later, the USA Centre for Jury Studies drew on subsequent debriefing experiences to suggest that modern technology was adding to juror stress: “Rather than having the chalk marks on the pavement as to where the body was, you’ve now got a videotape — a color videotape.”

The following year, 1995, proved to be a bellwether one for the nascent field of juror stress, with the trials of O J Simpson in Los Angeles, serial killer and rapist Paul Bernardo in Toronto and serial killer Rosemary West in Winchester, the first in England where jurors were offered counselling.

Trial judges micro-managed the emotional consequences of trials ad hoc. For example, in the English trial of Paul Esslemont for the strangling and beating of a three-year-old, the judge modified the evidence before the court to protect the jurors: “Those photographs had been considered by those who prepared the documents to be of a horrific nature.

“Accordingly, the photograph which was shown to the jury of the little boy’s body in position in the foliage had a small piece of yellow paper approximately one inch or three-quarters of an inch square, put over the face. It left the photograph sufficiently clear for the jury to be able to see the position in which the body lay and what were its surroundings.”

However, the trial judge, recognising that the wounds on the toddler’s face may be relevant to disputes in the case about the blood on Esslemont’s golf club and shoes, told the jury: “When you retire a copy of the photographs in their full form will go with you. You do not have to look at them if you do not require to do so, but it may be that some of you will want to, particularly when you come to consider the vitally important matter about where blood might fly and so on.”

Politics & Society

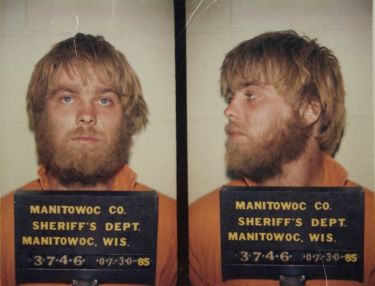

The ‘Making a Murderer’ effect

After the O J Simpson verdict, The Mirror noted the onerous conditions imposed on the jury during that trial: “And the O J Twelve lived under unusually strict rules — NO locked doors to their rooms, NO booze and NO small gatherings. They were either all together or each one alone.”

Justice Blofeld reportedly imposed much the same conditions on the jury at Stephen Young’s retrial. David (one of the jurors) described how the jury coped after delivering their verdict: “We went into the jurors’ room again and everyone’s sitting there sobbing. It was...for five weeks nobody had had any physical contact but there was people cuddling, there was holding hands, there was people saying goodbye and we were actually in that room for an hour before we could compose ourselves enough to actually leave the court.”

The end of hotel stays for English jurors a few months later would allow jurors to seek the solace of their families and friends while they deliberated. However, section 8 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981 meant — and still means — that they cannot lawfully talk about their actual deliberations to anyone, including family and psychologists.

The ouija board jurors’ distress

The circumstances of the four Ouija board jurors bear close consideration. There is every reason to think that they (and their eight colleagues) were just as distressed as the retrial jury was by the evidence about Nicola Fuller’s death (which included a disturbing recording of Mrs Fuller phoning emergency services but unable to speak due to a bullet wound in her cheek).

Politics & Society

Judge, jury and Google

They also faced the burden of having their private behaviour (and possible turmoil) outed and scorned by a tabloid, investigated by a police officer, condemned by multiple courts and pilloried by a host of lay, legal and academic commentators. The Court of Appeal’s judgment accused them (on doubtful evidence) of believing in ghosts, annulled the result of their five weeks of service and laid the blame on them for the many costs of the re-trial. The Contempt of Court Act 1981 continues to largely bar them from explaining their actions. While nothing can come close to the traumas that the victims’ deaths imposed on their families, the Ouija board case is also a potent lesson on the traumas the jury system itself can cause and the dangers of not taking steps to manage the stresses of the juror role.

Whatever the merits of jury secrecy, there is no excuse for limiting ourselves to arid legal argument, mock horror and amusing anecdotes on those occasions when we lift the veil. Rather, we should seek to understand what that jury experienced, including learning about the task they were required to undertake, the evidence they were made to consider and the effect those things had on them and others. Not only should we be prepared to approach their seemingly outlandish behaviour with sympathy but we should always ask: what might we have done if we had to bear their burden?

If that stance had been taken from the outset when it came to the Ouija Board case, then the tale would have, I believe, prompted small but important changes to how we assist jurors in their role.

‘The Ouija Board Jurors: Mystery, Mischief and Misery in the Jury System’ is published by Waterside Press. More information is available here.

Banner image: iStock