Politics & Society

How Australians should watch the US election

As important as the analysis of this White House race will be, Donald Trump’s re-election as US president must be understood against the broader sweep of American history

Published 7 November 2024

How has it come to this? For many observers outside the United States, it is almost inconceivable that Donald Trump has reclaimed the American Presidency.

But he has.

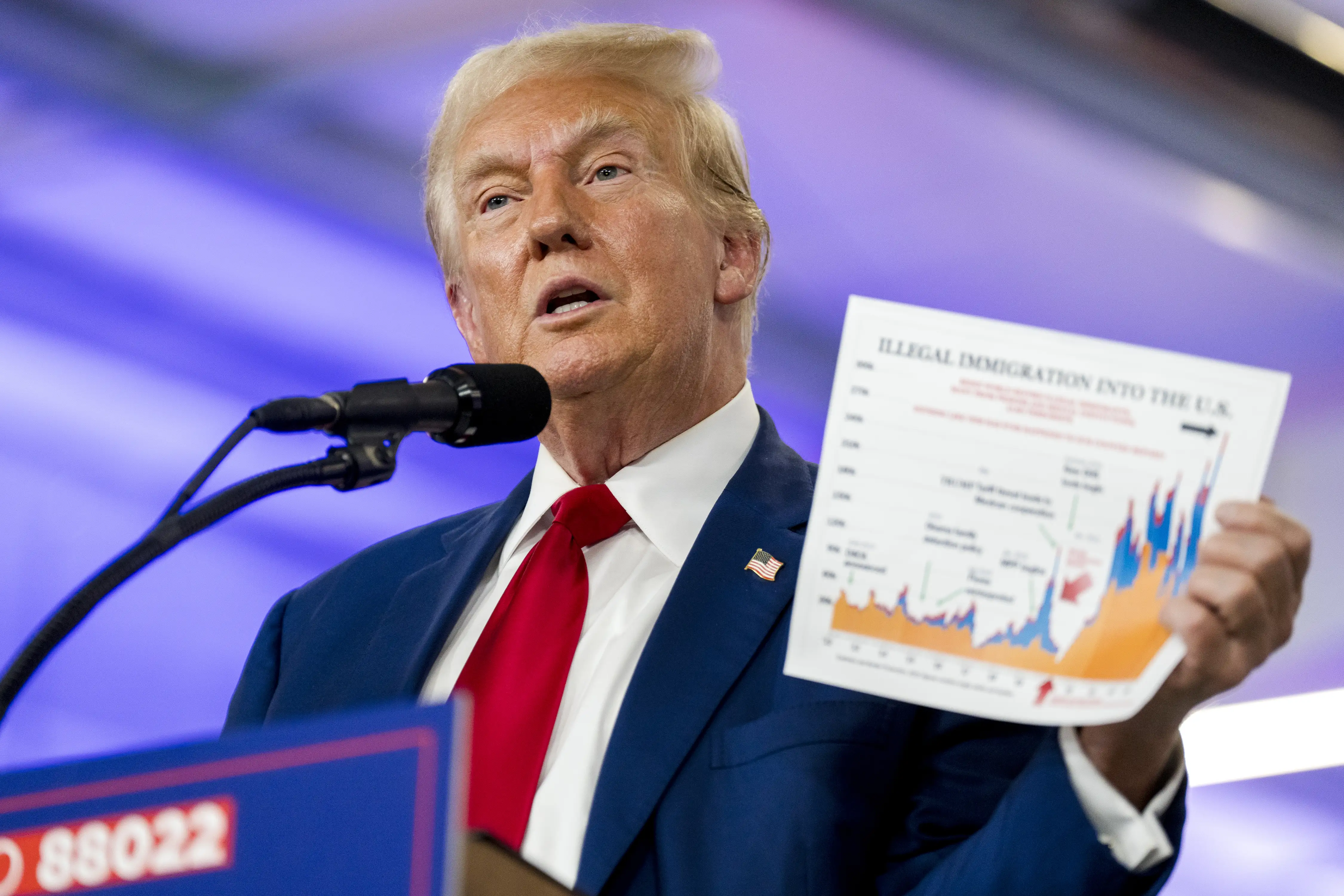

Trump is a convicted felon who, just three years ago, goaded hardcore supporters into an insurrectionary assault on the capital to impede the peaceful transfer of power. A judge found accusations of rape against him to be "substantially true". He has a long history of trenchant racism. He was impeached by the House of Representatives.

He illegally hid nuclear secrets in his bathroom. He was ejected from office amid the calamity of his COVID response.

He seemed to be falling apart on the campaign trail – at one infamous event, he spent 40 minutes swaying to music. He promised violence and retribution if he returned.

He was just, weird.

Politics & Society

How Australians should watch the US election

All of that is just the beginning of the extensive jeremiad of his inadequacies for the role. In short, he defies every expectation about what a president should be.

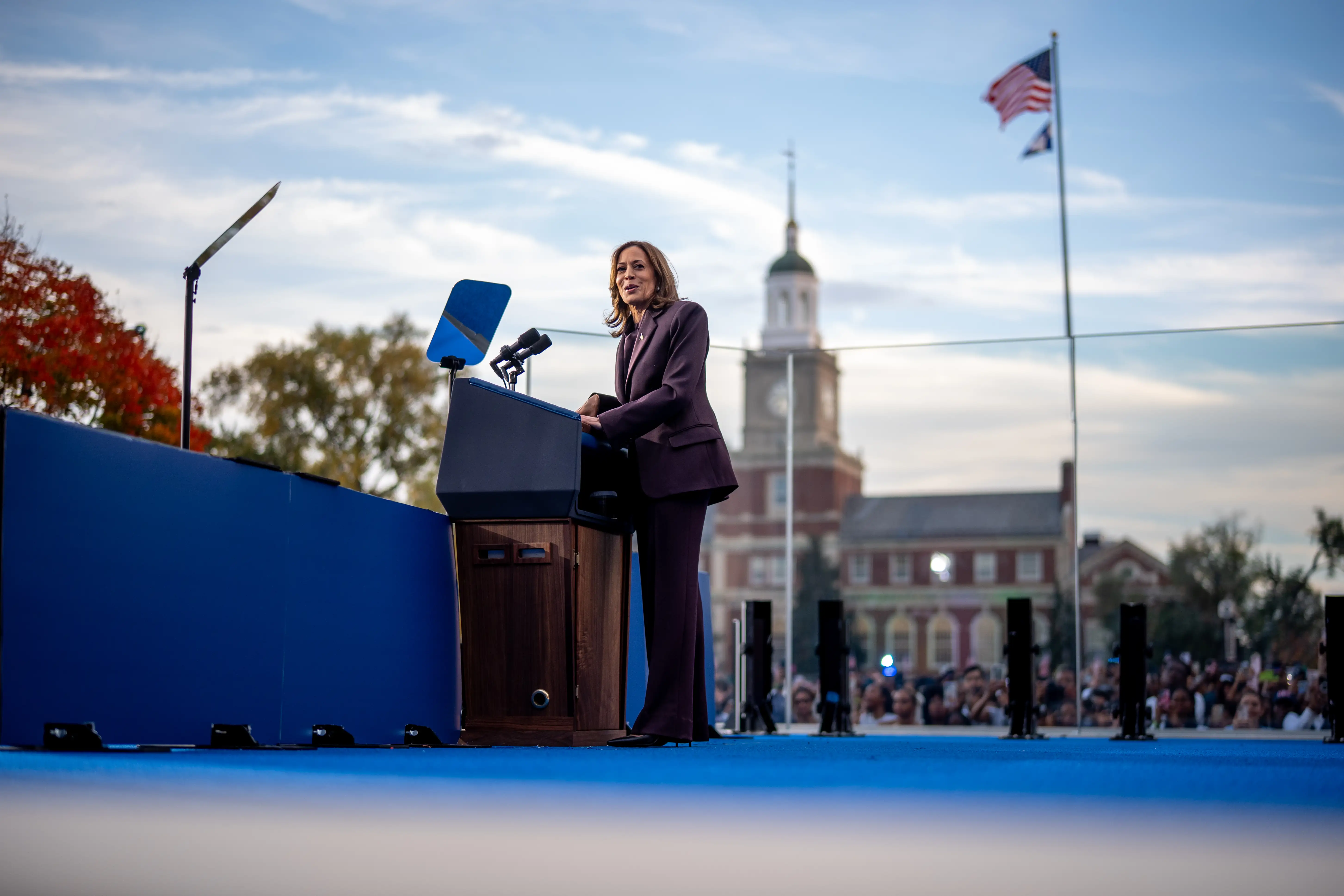

On the other hand, Kamala Harris is Vice President, a former Senator and previously a prosecutor. It would be difficult to be more qualified for the role. Harris had a strong feel-good factor among her supporters, she trended on TikTok.

She stood poised to make history as a woman with African American and Indian heritage running for the presidency. Her supporters emphasised her intellect, competency and warmth.

And yet this did not seem to matter. Political convention and basic decency did not seem to matter.

In 2016, at least there was the alibi of a relatively close contest, with Trump losing the popular vote. His opponents can be sated by no such cold comforts this time.

Now the mythologising of the victory begins. And, just as importantly, the Democrats and Harris will be exposed to extensive post-mortem of the loss.

Before the night was out, commentators who hadn’t predicted the result were already confidently pronouncing how this had happened, tracing the twists and turns of the campaign trail, trying to identify the pivotal moment when the campaign turned.

There was plenty to talk about: the dual assassination attempts on Trump, votes shifting from traditional strongholds of Democratic support, the loss of what was once a ‘blue wall’, Harris’s disconnect with voters and inability to distance herself from Biden, cost-of-living and the economy, the continued radicalisation and racialisation of migration politics, and how dissatisfaction with the Administration’s response to Israel’s assault on Gaza has turned voters away from Harris.

Politics & Society

What a mixed-race presidential candidate means for America’s diversity

Important as this analysis of the past few months will be, to truly comprehend how Trump was able to return to office and to grasp the deeper significance of this political moment, it is necessary to consider the broader factors that have propelled Trump to the White House once again.

One of these factors is a product of the contemporary moment, but this itself can only be understood against the broader sweep of American history.

Trump has dominated American political life for the past decade.

How did he develop such a strong chokehold over the Republican party, spearhead a movement and recast American politics in his own image?

Trump has proven himself to be an extraordinarily successful avatar for a well-established reactionary mobilisation with deep roots through American history.

This has been a vital component of his enduring appeal to a significant swathe of the American population and – as well as the overwhelming majority of the Republican party.

He has given expression to the dark and elemental howl of rage and resentment of conservative voters who embody an intertwined racial revanchism and Christian supremacy.

While he has built upon his electoral coalition, this is the core of his social base – those who have been with him through thick and thin.

These voters are the inheritors of the white conservative backlash against the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. This backlash was spearheaded by political agents (often cloaking themselves in evangelical Christianity) who sought to reassert racial and cultural hegemony over the United States.

Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

They proclaimed ‘states rights’, fought to impose ‘traditional’ values under the cover of preservation, and articulated a strategy to utilise and capture key mechanisms of American state power to enforce their will over the majority.

Yes, the presidency was always crucial to their plans, but so was control over state houses, governorships, the Senate and the Supreme Court.

This formed the basis of a new social movement, premised on the rejection of the advances of the civil rights movement. Its adherents despised all those they perceived as a threat to the social order they sought to (re)create: mobilised Black Americans, feminists, lesbians and gays, migrants and anybody else who could be broadly described as ‘liberal’.

At the centre of this mobilisation was wealth and power.

Conservative billionaires found ready allies in this movement. Republican politicians were happy to speak their language and pursue their aims, a strategy that delivered a coherent bloc of votes and a dedicated activist core.

Hence, the well-recognised congealing of neoliberalism and neoconservatism on the American right.

But this uneasy alliance began to fray.

The key event was the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, which upended established certainties and tore at the social fabric.

This expanded the space for conspiratorialism, millenarianism and the outright rejection of established norms of politics. It also allowed for racialised targeting of historically excluded and oppressed groups – Black Americans and migrants prime among them.

This also included a resurgence of antisemitism and anti-Asian racism.

Trump spoke directly to a section of the Republican electorate who had already been radicalised.

They didn’t care that he defied convention, that he wasn’t from the ‘establishment’, that he consistently violated codes of basic decency, that he was a racist, that he was a sexist who boasted about groping women.

They cared only that he spoke for them and their conviction that politics was biased against them, that ‘elites’ had unfairly displaced them from their rightful prominence, and that this was all going to change.

Make America Great Again was only ever an appeal to return to the racial order of the 1950s and 1960s. Trump knew it. They knew it. And that’s why they loved him. That’s why they love him still.

This was the core of the support that led Trump to the White House in 2016.

The second major factor is the extent of social fissures within the United States in the previous four years.

For all his many faults, President Biden did demonstrate himself willing and able to propose an agenda that was expansive. He conceived of how best to reach out to communities who considered themselves discarded by the mainstream of American economic and political consensus in recent decades, while still delivering to those communities who have borne the brunt of exclusion.

This agenda promised a break, albeit minor from the neoliberal orthodoxy that has dominated US economics and politics in recent decades.

But this was impeded at every turn.

Health & Medicine

Is rising inequality fuelling our moral outrage?

Early attempts to use state power to drive economic resurgence were stymied from within Biden’s own party, his desire to be a great conciliator prevented him from using the overt power of the presidency to break the deadlock.

Reform was stalled, watered down and inadequate.

At the same time, the cost-of-living crisis and inflation drove resentment. A sense that America was flailing, directionless. It was fertile ground for bad-faith actors to recruit based on false promises, grievance, and mobilised hatred.

It was the perfect ground for Trump.

Trump has the rare benefit of the prestige of the presidency without the baggage of incumbency. In today’s hyper-fast politics, four years was an eternity ago.

He was able to recast himself again as an outsider, a saviour. And he was bolstered in this by powerful new friends.

Elon Musk was the most overt billionaire who extolled Trump’s virtues as a cultural warrior and defender of free speech. The fact that Trump also opposed Democratic measures to increase corporate taxes and expressed willingness to cut regulation as the precursor to innovation underlies the appeal.

This was reinforced by cultural influencers with mass appeal, especially among men, like podcaster Joe Rogan.

Trump presented himself as an iconoclast. A raw, unrepentant, masculine expression of defiance of an established order that he argued simply did not speak to large swathes of Americans.

He presented himself as the one willing to speak the truths that nobody else would.

Politics & Society

What happened in the US was Very Bad

Beyond the twists and turns of the campaign, one fundamental truth needs to be understood: for the third successive election, tens of millions of Americans cast their vote for Donald Trump.

American democracy is facing an existential threat without modern parallel. Trump will be back in the White House with a coherent and extensive plan to recast American society.

Republicans will hold the Senate, and most likely the House. Conservatives dominate the Supreme Court.

The Democrats will be in disarray, their capacity to resist enervated.

Trump speaks to a reactionary mobilisation that explicitly rejects the norms of American politics. It is a movement that does not want to embrace a diverse, modern, and equal future. It is explicitly built upon its rejection.

This is the basis of the existential crisis gripping America, and the terrifying reality Americans – and the world – all have to face.