Truth-telling and re-naming is an opportunity to redefine our future

Physical education pioneer Fritz Duras had a distinguished career, but our truth-telling process uncovered another side to Duras that can’t be ignored

Published 6 December 2024

In October 2024, the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Education renamed its Fritz Duras Memorial Lecture the HOPE (Health, Outdoor and Physical Education) lecture.

This series of biennial lectures dates back to 1968.

The Faculty explained the change as a response to “recent evidence regarding his membership in the Eugenics Society of Victoria ".

The research to which this refers is Dhoombak Goobgoowana: A history of Indigenous Australia and the University of Melbourne, edited by ourselves with Professor Marcia Langton.

The lecture was named for Duras with reason, given his formative place in the history of the Faculty of Education. But there are good reasons, now, for his name to be removed.

Who was Duras and why was the lecture named after him?

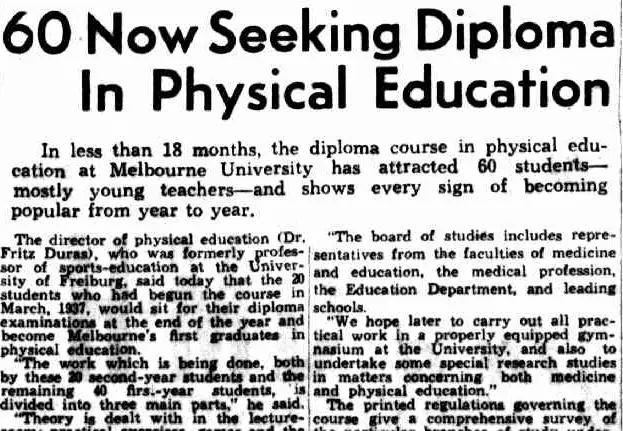

Fritz Duras arrived in Australia in March 1937 at the invitation of Raymond Priestley, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Melbourne.

Duras was a decorated First World War veteran and medical doctor who had become director of the Institute for Sports Medicine associated with the University of Freiberg.

He had been dismissed from his position because of his Jewish heritage but was supported by the Carnegie Corporation to come to Australia. Duras joined another Jewish refugee, meteorologist Fritz Loewe.

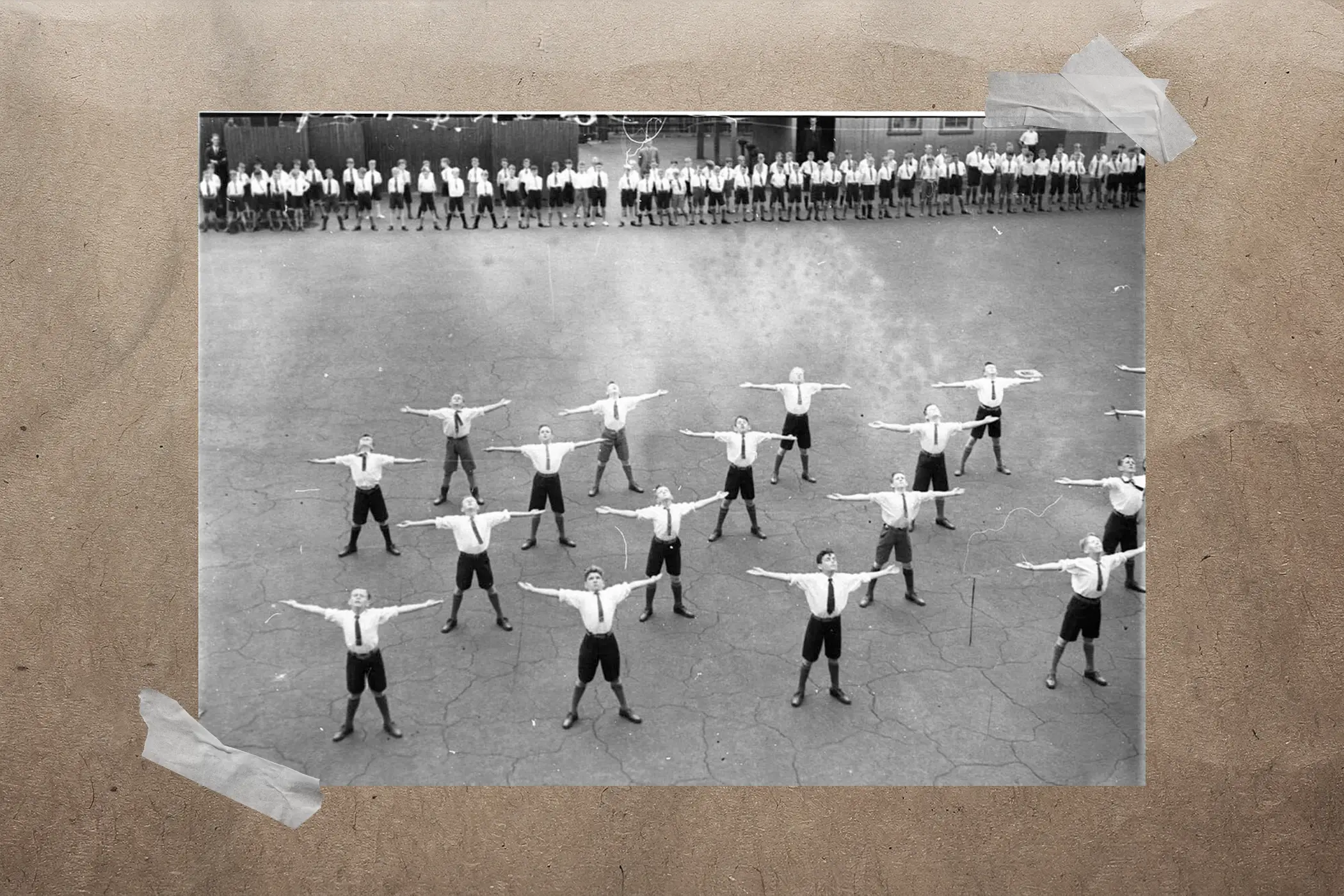

Duras presented the University with an opportunity to hire a skilled physical education teacher and launch a program to train physical education teachers.

The aim was also to incorporate various forms of gymnastics and physical movement through exercise clubs and societies.

With the strong support of the Faculty of Education and its then-dean George Browne (another member of the Eugenics Society of Victoria), Duras established the first university physical education course in Australia.

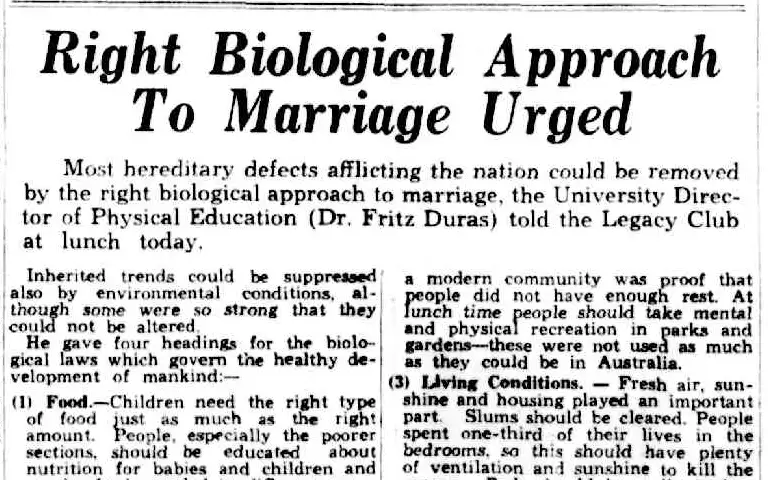

This was a growing field that captured imaginations and Duras became a public intellectual with a wide audience. Articles delighted in quoting this German expert, who advocated “scientific physical culture methods” and who drew liberally on his German heritage as a marker of his authority.

Even while rejecting totalitarianism, Duras recommended the adoption of methods he had seen in Germany, which he saw as developing a “eugenic conscience” that aligned with other international movements, including the “English Society.”

Duras promoted nutrition and lifestyle as the pillars of preventative public health. This included a healthy diet, sufficient rest and recreation in public parks and gardens.

He advocated ventilation in the home and the airing of beds – chiding “housewives” who made the bed too early each day without first letting it air. Sun and air bathing promoted better muscle definition, and he highlighted the moral and mental health benefits of socialising through sport.

However, also bound up in these ideas was a focus on what he called “the poorer sections” of society.

Politics & Society

What Canada can teach us about truth-telling and justice

He believed these people were most in need of education about these matters, and he urged that “slums should be cleared”.

Why the difficulty now?

These get-fit and eat-well ideas informed his concerns about the “health of the race”.

After his arrival, Duras joined the Eugenics Society of Victoria, which had been established in 1936. Its founding president was University of Melbourne professor of zoology, Wilfred Agar, and it included members from across the University and Melbourne’s professional classes.

The Eugenics Society distinguished itself from a range of similar societies by its emphasis on scientific authority.

It focused on genetics and the control of “innate inherited factors” in the population, which would “be achieved if the future generations are produced mainly by persons likely to transmit good qualities of mind and body”.

Meanwhile, those “persons with gross defects of mind or body, known to show a tendency to be inherited, should be discouraged or prevented from producing children”.

Duras’s main contribution to the eugenic cause was his championing of pre-marriage counselling and the introduction of marriage licences, signed by medical professionals.

These ideas overlapped with his public health campaigns. For example, they were motivated to control venereal disease, the prevalence of which was regarded as a significant public health issue.

Pre-marriage counselling and marriage licences were also directed at discouraging those people the Eugenics Society regarded as inferior members of the race from having large families.

These people encompassed a significant portion of the population, including the disadvantaged members of inner-urban slums, Indigenous people, homosexuals, those with mental illnesses and those with heritable physical disabilities – who were all crudely grouped together.

Health & Medicine

One of the most affecting and unsettling things I have ever seen

At its most severe, pre-marriage counselling would be exercised to facilitate sterilisation of those with “hereditable physical and intellectual disabilities and mental health”, as Duras told an audience at a Eugenics Society lecture in 1938.

This would improve national fitness, but also reduce the “burden” of supporting “the insane and crippled”, which involved “enormous sums” and “far exceeded” the cost of “welfare institutions for healthy people”.

“In Germany”, he argued “it was compulsory for those who intended to marry to present health certificates setting out their own condition and their family health history.

“In certain cases of mental infirmity couples were not allowed to marry without sterilisation … children should not be brought into the world if they were going to be a burden on society and the State.”

Duras’s ongoing advocacy of these ideas, including after the war, make him unsuitable to be honoured by a named lecture.

Truth-telling requires a precise and fully documented account of the past to give appropriate context to a person’s life and work and to ensure that they are not erased from history.

By understanding this history, and ensuring that it is not lost, mistakes of the past can educate our future.