Health & Medicine

Breakthrough in motor neurone disease research gives hope

A decade-long mission to make epilepsy better understood has resulted in a new way of classifying the condition, promising more effective treatment for patients

Published 13 March 2017

On the day she upended the medical landscape, publishing work in an international journal that will revolutionise the way epilepsy is recognised, defined and treated, paediatric neurologist and University of Melbourne Professor Ingrid Scheffer conducted her regular clinic. Dealing with patients new and old, she wrangled – as she has throughout her 25-year career – with the diabolical mysteries and shattering trickery of epilepsy.

A little girl. A young boy. A teenage boy. A young man. A middle-aged woman. Each suffering some form of epilepsy, a condition that causes recurrent, unprovoked seizures or fits, brought on by some interference in normal brain activity. Each with a story powerfully illustrating why the decade of effort by Scheffer and her colleagues to overhaul the outdated 30-year-old classification system for epilepsy is so seismic.

The new system, just published in the journal Epilepsia, describes seizure types that weren’t even recognised in the old classifications, enlists plain language to build awareness and understanding, and updates information across the spectrum to allow patients and doctors to be better informed on causes, risks and associations with other conditions, all knowledge that will inform better management.

Patient A: The nine-year-old girl began having convulsive seizures as a toddler. Medication quelled these episodes, but this was not sufficient to stop them taking a devastating toll on her development. As Professor Scheffer examines her she notices that the girl is zoning out, her eyelids fluttering – “absence” seizures. They might last only five seconds, but they happen every minute or so, perhaps all day, every day. Untreated, they will further stymie her progress, and may ultimately determine whether she can live an independent life.

“The mum has not known why she has this severe disorder,” Professor Scheffer says, “and today I told her that we had found the answer.” A mutant gene. Until 1995, the general belief was that epilepsy was the consequence of brain trauma – a bump on the head, a bad fall, a tumor or stroke. Then Professor Scheffer and her one-time PhD supervisor and longtime collaborator Professor Sam Berkovic, also of the University of Melbourne, together with genetic scientists at the University of Adelaide and in Germany, found the first gene for epilepsy. The world-leading group has since identified dozens more. This little girl has one that the team found in 2013, working with gene-finding collaborators from the US.

Health & Medicine

Breakthrough in motor neurone disease research gives hope

Now her family, and doctors, have a cause, which might pave the way toward intervention. “But I always say finding the gene mutation is just the beginning of the answer,” Professor Scheffer explains. In the era of exploding precision medicine, this genetic information has potential to be engineered into a specific therapy that can manage the condition, but it can’t undo the damage already done.

Patient B: A 13-year-old boy, slight, with weakness down one side of his body. His condition was not inherited but acquired – he suffered a stroke when he was born. Professor Scheffer first saw him 18 months ago when he was having many seizures each day with stiffening of the weak side of his body.

She put him on a drug trial and suggested to his parents that epilepsy surgery may be his best prospect. This procedure disconnects the damaged portion of his brain which is triggering seizures. It’s dramatic but potentially life defining. If the boy’s seizures stop, “we allow the other half of his brain which is normal to get on and maximise his learning”. It’s not an option for patients like the little girl, whose brain is wholly compromised by her genetic makeup.

Patient C: A younger boy, very bright. He’s only had three seizures. The first time he was reading to his sister when he suddenly stopped, his eyes slid off to the side, his hand clenched in a strange posture, he vomited. It was all over in a minute. In the old language, this fits what is described as a complex partial seizure, but in the new system it is called a focal impaired awareness seizure, reflecting what family and doctors observe with words that mean what they say.

His next episode occurred a year later, a period of zoning out, more like an absence seizure. And then came a violent episode, jerking and stiffening his whole body – a so-called tonic-clonic seizure. His brain-wave tracing suggests one form of epilepsy, but the actual description of the seizure points to another.

Health & Medicine

Caught! The cell behind a lung cancer

Professor Scheffer is a bit stumped, trying to figure out which of the 40-something epilepsy syndromes he fits. She prides herself on mostly being able to nail it, though not all cases will fit in a syndrome “box”. She’s like a detective on a case. If she can figure out his syndrome, then the chances of managing it, and sparing him limitations in his future life, such as driving, will be immeasurably boosted.

Patient D: A man in his mid-20s with a “very nasty” genetic form of epilepsy. Professor Scheffer first saw him when he was a child, and is thrilled at the “fantastic” functional lifestyle that he has achieved. He’s independent, formed relationships, qualified and found work in an adult day centre, a context that is reassuring and supportive for him. “They will cope there if he has a seizure. He’s a cool chap, a great role model for the patients, who will love him.”

Epilepsy is still burdened with stigma and misunderstanding, and many people with a milder or moderate diagnosis who could work usefully and productively across the gamut of occupations are marginalised, by ignorance or fear, or by their own lack of confidence and concerns that they might not find the support they need if they have a seizure.

Patient E: A woman nudging 40, who first came to Professor Scheffer as a 16-year-old. When the doctor told the parents that brain surgery would be their daughter’s best option, like many parents they bolted – scared off by this dramatic step. But when she turned 20 the girl came back and asked for the surgery herself.

“I have a photo of her sky diving at 21,” she says. The woman is essentially seizure free, a high-achieving, independent professional, but still with the wormholes of epilepsy eating away at her confidence.

“Even when epilepsy is mild and controlled, it makes life far more challenging,” says Professor Scheffer. “And then with these really severe cases in children, it is affecting their learning, every aspect of their life, which is so much harder.”

The hunger for this overhaul of epilepsy classification, from doctors and patients, was made plain when Professor Scheffer, who is also the Director of Paediatrics at Austin Health, and her colleagues published their preliminary paper back in 2010. It generated more than 1500 citations. It’s taken epic rounds of consultation in the years since to refine descriptions and language to be useful across cultures, and accessible to both specialists and patients. The Epilepsia papers include two articles that outline changes in the new classification, and a guidance article on how to use the classification in clinical practice.

Epilepsy, says Professor Scheffer, is still an extremely complex, baffling, misunderstood field – for many medical professionals, let alone individuals or families who suddenly find themselves confronting a diagnosis. “Which is what this paper is about. It is where the clinical research is so critical, and that is what I’ve done with Sam Berkovic over 25 years.”

About 50 million people in the world have epilepsy – in many it manifests as mild, not severe. In 70 per cent of cases it begins in childhood or adolescence. In about 70 per cent of those cases it can be controlled easily with medication, and a lot of children grow out of it.

Professor Scheffer’s fascination has been in exploring the roulette of genetic abnormalities that manifests as epilepsy. Once they were the “unsolved” categories of epileptic cases, “but my estimate is that now about 50 per cent of the severe epilepsies of infancy and childhood are solved, although the majority of common forms with a genetic basis remain unsolved. Our research team is looking to solve the ones that aren’t, finding new genes, and new diseases, and new treatments”.

She’s been part of a revolution in understanding and responding to epilepsy over the past 20 years. What are her hopes for the next 20 – will epilepsy be “fixed”?

“Will I see it in my lifetime? I don’t know,” she says. “For some, yes. With these profoundly disabled kids, a lot of the lack of function is because epilepsy stops developmental processes very early in life. But I would hope that we would have treatments that would improve their outcome. A cure? I would love it, but … maybe I’m too realistic to promise that right now. I am optimistic that all our work will lead to a cure in the future.”

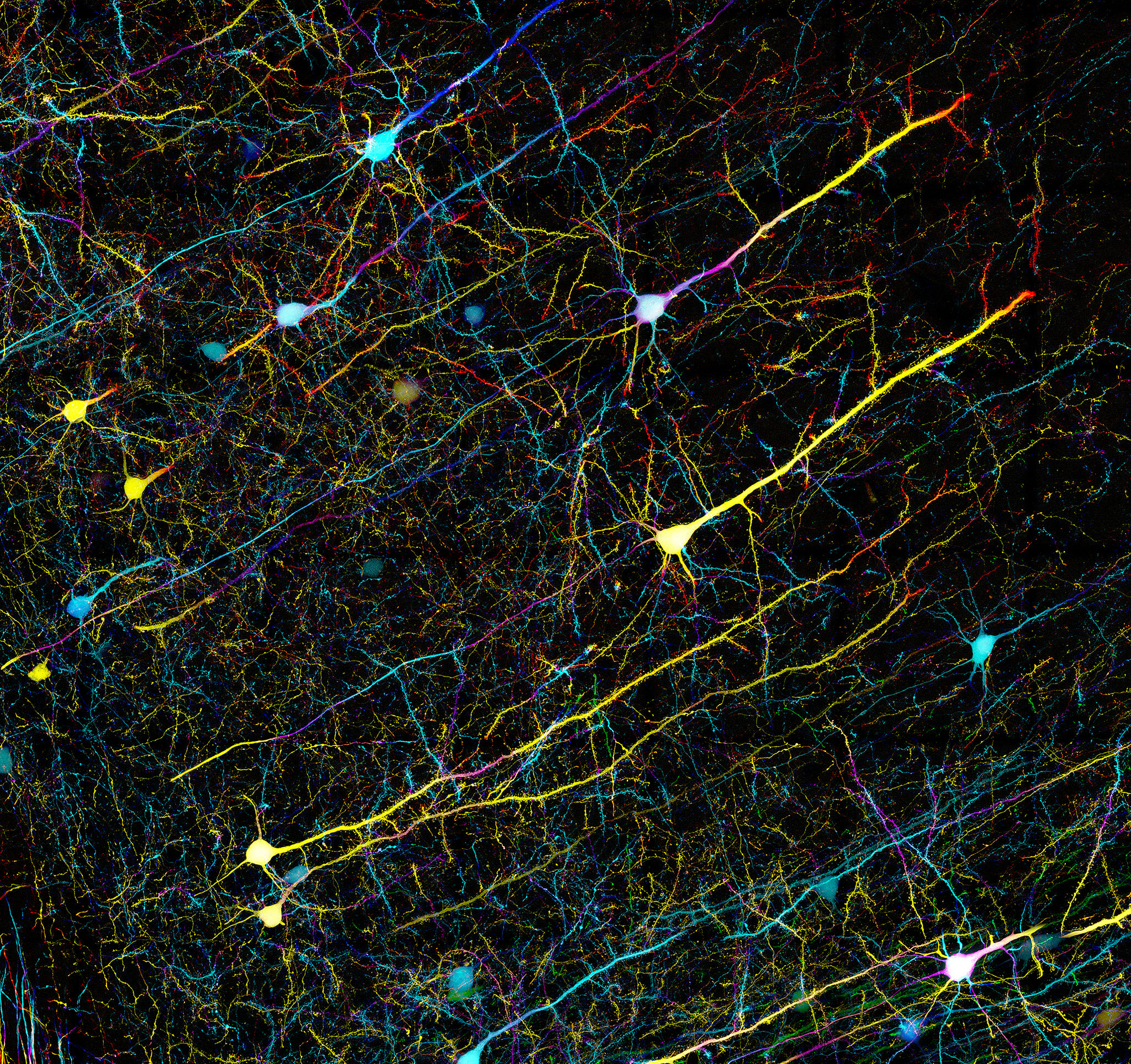

Banner image: ZEISS Microscopy / Flickr