Health & Medicine

War and trauma: Learning the lessons

After three years, the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide delivered its recommendations, but for those of us affected, it’s seeing real change that matters

Published 16 September 2024

Content warning: This article discusses suicide and suicidal thoughts which some people might find upsetting.

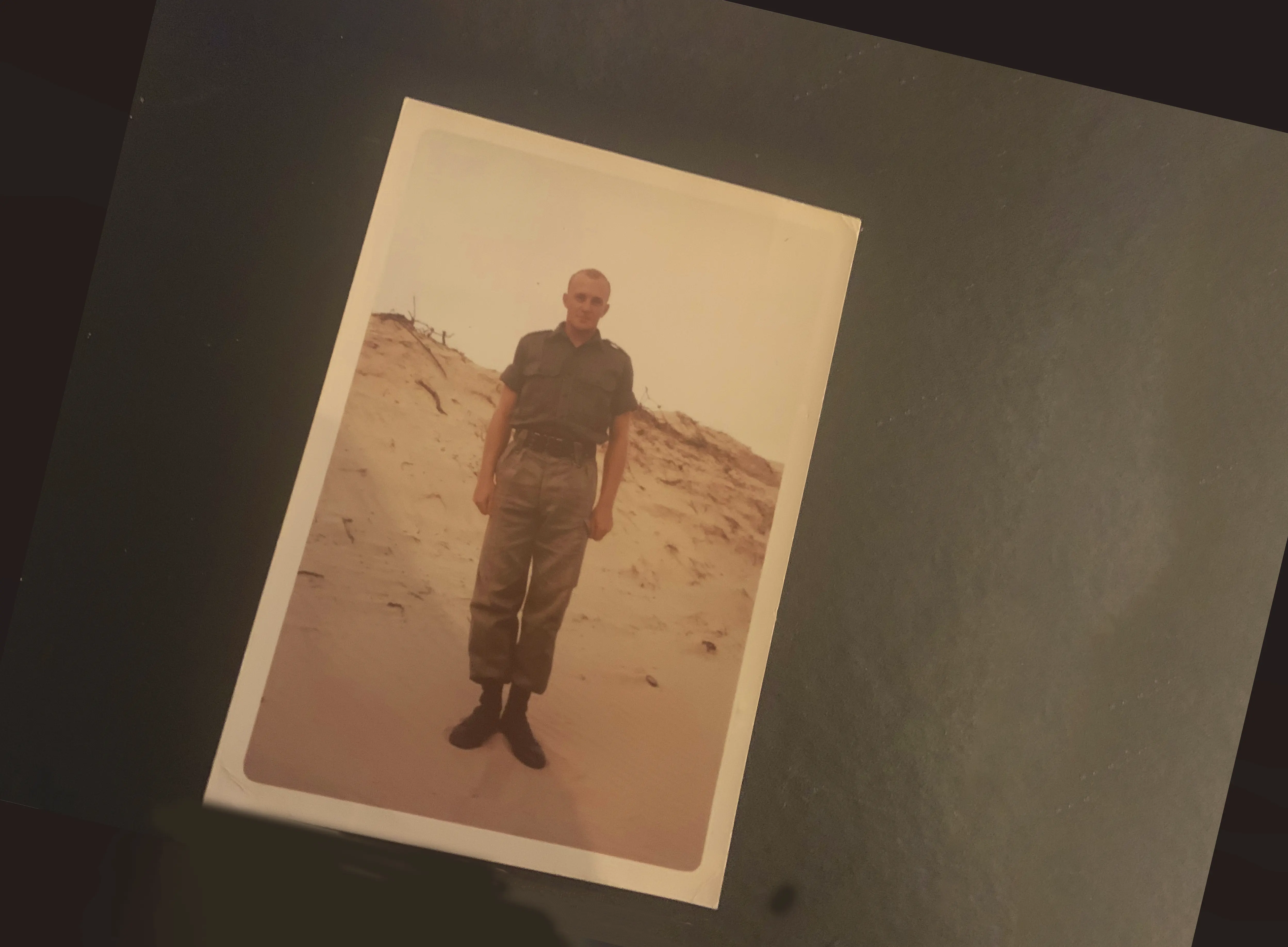

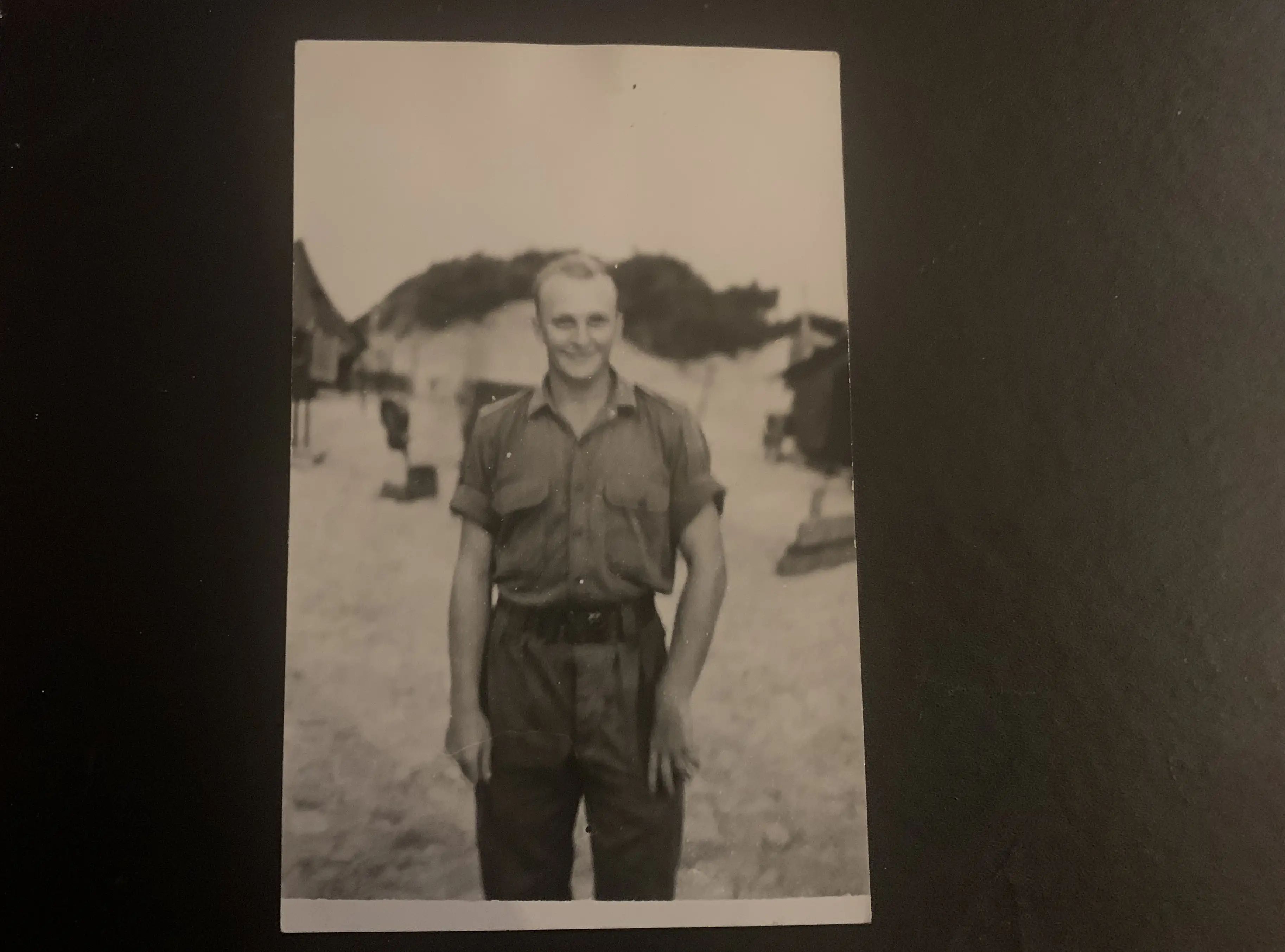

When I was growing up, we couldn’t get up in the middle of the night and go to the bathroom without my father whispering, “Who’s that?”

It didn’t matter how quiet we tried to be, my father, a Vietnam War veteran, always heard us. He hardly ever slept and, when he did, there were his nightmares.

But when he was awake, he was just as restless, irritable and on-edge. You never knew what mood he’d be in, or if you might say something that could turn out to be an emotional landmine.

He was always arguing with my mother. Then there were the things that would make him break out in a sweat – crowds, sudden noises and choppers.

He never talked about Vietnam, his army service, or his feelings – of course. Real men didn’t.

To the rest of the world, he was Mr Reliable, a really good guy, always ready for duty – rain, hail or shine.

Health & Medicine

War and trauma: Learning the lessons

Then, after holding it together for about 30 years, it all became too much even for Mr Reliable.

He started having outbursts at work (not just at home). He became shaky and withdrawn. Suddenly, he said he felt very attracted to train tracks.

For him, opening up about feeling suicidal was what finally got him the medical treatment and social support he needed. It was also the start of a long, protracted and demoralising battle with the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) to get them to recognise his war-related injuries documented over decades in the government’s own records.

But my father was one of the lucky ones.

According to the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide, which has recently been tabled in Parliament, at least three people every fortnight who served in the armed forces have taken their own lives.

Men who have been in the armed forces have a 30 per cent higher risk of completing suicide than employed men in the general Australian population. That risk increases to 50 per cent for men who have been in combat or on a security mission.

It is 110 per cent for women.

But these numbers probably underestimate the problem, because the Royal Commission only considered suicides for those who served in the armed forces after 1 January 1985 – missing a lot of Vietnam veterans.

Health & Medicine

Restoring the lives of Australians with PTSD

As my father would say, having been to a lot of ex-servicemen’s funerals – who knows if that car accident was really just an accident?

The bottom line is that far more people who have been in the armed forces are dying from suicide than on the battlefield – and that risk can persist for years.

I am a mental-health and disability lawyer, so the Royal Commission is of professional and intellectual interest to me.

Given my own experience, it was hard for me not to read it without feeling a range of emotions – relief, anger, sadness and fear. At times, I read it through tears.

I felt relief because, thanks to the intense lobbying of the defence and veteran communities, the issue of suicide was finally being recognised and taken seriously.

After three years, seven volumes and 3000 pages, the Final Report was enormously thorough.

While combat is almost unavoidably traumatic, what the Royal Commission showed was that the real cause of the suicide epidemic was systemic and embedded in a toxic defence force culture.

The 122 recommendations are logical and sound about the need for prevention; early intervention; better communication, coordination and collaboration across the whole defence and veteran ecosystem; building the capacity of Defence and DVA to prioritise health and wellbeing on par with capability and performance; and increased oversight and accountability.

Health & Medicine

Understanding posttraumatic nightmares

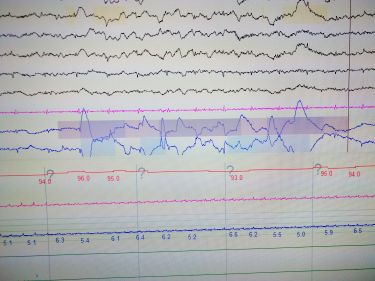

The Royal Commission helped me understand a lot of things about my father – for example, the way the training rewards hypervigilance, reinforcing PTSD.

And why it had been so difficult to get him help – the institutional ‘cone of silence’, the culture of self-reliance and self-sacrifice, the difficulties getting medical and mental health concerns taken seriously.

Apparently, being called a “malingerer” is the worst and most shameful insult in the military.

I understand now why my father used to worry that everyone, including the DVA doctors, would think he was ‘making it all up’, even when it was patently obvious that he most certainly wasn’t.

But the Royal Commission also made me angry, because it showed how little regard Defence and DVA have had for the health and safety of our service men and woman in an inherently mentally and physically dangerous workplace.

The psychosocial hazards in the armed forces noted by the Royal Commission are well-documented causes of mental ill-health and suicide in the research literature.

These include bullying, harassment and physical abuse, sexual violence (most commonly against women by men), exposure to traumatising events, excessive workloads and burnout (made worse by recruitment shortfalls), and organisational injustice and job insecurity – some discharges are forced and difficult to fight.

Recent changes to Australian case law and the Work Health and Safety regulations mean civilian employers are required to eliminate or reduce these well-known psychosocial hazards.

Health & Medicine

Can alternative therapies help PTSD?

But, there are also added psychosocial hazards identified by the Royal Commission that are unique to, or magnified by, the armed forces.

These include separation from family and the risk of relationship breakdown; a rigid military hierarchy in which senior offices abuse their power with impunity; intense loyalty to the institution and “moral injury” when feeling betrayed by it; lack of concern about health and safety procedures (including recent revelations about blast trauma on the brain) leading to preventable physical injuries during training; and encouragement not to report injuries, seek help or spend time recovering.

Then there are the problems associated with transitioning back to civilian life and the difficulties of dealing with DVA.

Following revelations of widespread misconduct in parliament and in the Set the Standard: Report on the Independent Review into Commonwealth Parliamentary Workplaces (the Jenkins Report), there was much outrage that parliamentary staff did not have the same employment protections as other Australians.

Well, the Royal Commission found that neither do our armed service personnel and veterans – despite their enormous sacrifices.

Worse still, the systemic and cultural problems within the armed forces that culminate in suicide are also driving down recruitment and retention. Suicide is no longer just a national tragedy – it is also a national security issue.

Then, my anger turned to sadness.

Politics & Society

Building mentally healthy workplaces

For the unnecessary suffering of our service men and women, when these issues have been known by leadership for decades and have been documented in over fifty previous enquiries and reports.

For their families, who are so much more than a “resilience factor”, and their own suffering as they support their armed force members and veterans – too often losing them to suicide.

Finally, reading that report, I felt fear.

The armed forces are often regarded as ‘unreformable’. And, having seen the Federal government’s disappointing response to the recent Aged Care and Disability Royal Commissions, I fear that many of the recommendations of the Veterans Suicide commission will also fall by the wayside.

The Royal Commission invites the public and the media to keep up the pressure for the implementation of the recommendations.

So do I.

We must all get behind the Royal Commission and keep the government accountable for reducing the unacceptable rate of suicides among the women and men who bravely put life and limb on the line to protect us all.

If you or anyone you know needs help or support, please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14. There’s also crisis and community support options available on the Royal Commission website.