Unlocking the inner workings of plant growth

Sustainable biofuels are closer to reality after the discovery of a key step in plant cell wall production.

Published 24 June 2016

Plant cells walls – we eat them, wear them, make furniture and houses out of them and use them as a fuel. Their properties have a huge influence on how they are used, and researchers are now one step closer to understanding how they are produced by plants.

An international team of scientists have identified several proteins that are essential to producing the main component of plant cell walls – cellulose. This substance provides the strength to plants and the insoluble fibre in the human diet.

The findings may lead to improved production of cellulose and guide plant breeding for specific uses such as wood products and cellulosic ethanol fuel, which is estimated to have roughly 85 per cent less greenhouse gas emissions than fossil fuel sources.

The work, led by the University of Melbourne and the University of Cambridge, has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The newly discovered proteins are located in a part of the cell called the Golgi, where proteins are sorted and modified. Scientists named the new proteins STELLO, which is Greek for ‘to set in place, and deliver’.

One of the lead researchers, Professor Staffan Persson, from the School of BioSciences at the University of Melbourne, said the team found that the STELLO proteins were necessary for proper cellulose production in plants.

“Based on our data, we concluded that the STELLO proteins are likely assembly factors of the cellulose producing machinery and that they are important regulators of cellulose synthesis in plants,” says Professor Persson.

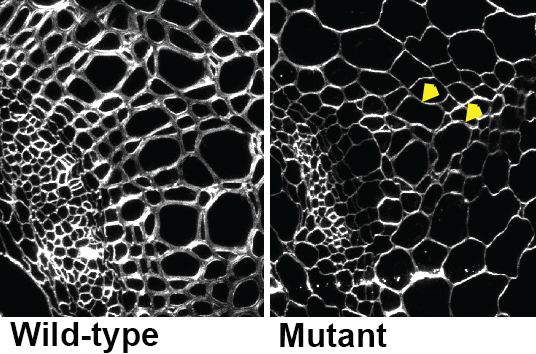

“Plants without the proteins cannot produce cellulose very well and the defect substantially impairs plant biomass production.”

The researchers made the discovery by engineering the STELLO proteins and the cellulose producing proteins to contain fluorescent tags, and then monitoring their behaviour in the cell using fluorescence confocal microscopes.

“The ultimate aim of this research would be to breed plants that have altered activity of these proteins so that cellulose production can be improved for the range of applications that use cellulose, including paper, timber and ethanol fuels.’’

Another lead researcher, Professor Paul Dupree from the University of Cambridge, said research to understand cellulose production in plants is an important part of climate change mitigation.

“Greenhouse gas emissions from cellulosic ethanol, which is derived from the biomass of plants, are estimated to be roughly 85 percent less than from fossil fuel sources.”

“In addition, by using cellulosic plant materials we get around the problem of the food-versus-fuel scenario that is problematic when using corn as a basis for bioethanol.”

Previous studies by Professors Persson and Dupree’s research groups have, together with other scientists, identified many proteins that are important for cellulose synthesis and for other cell wall polymers.

This new research substantially increases our understanding of how the bulk of a plant’s biomass is produced and is likely to contribute to the development of new industrial applications for cellulose and cellulose-derived products.

Banner image: Single seedling. Picture: skeeze (Pixabay)