US tariffs have backfired, and China is winning in Southeast Asia

Punishing nations for cooperating with China just pushes them closer to America’s economic rival

Published 14 April 2025

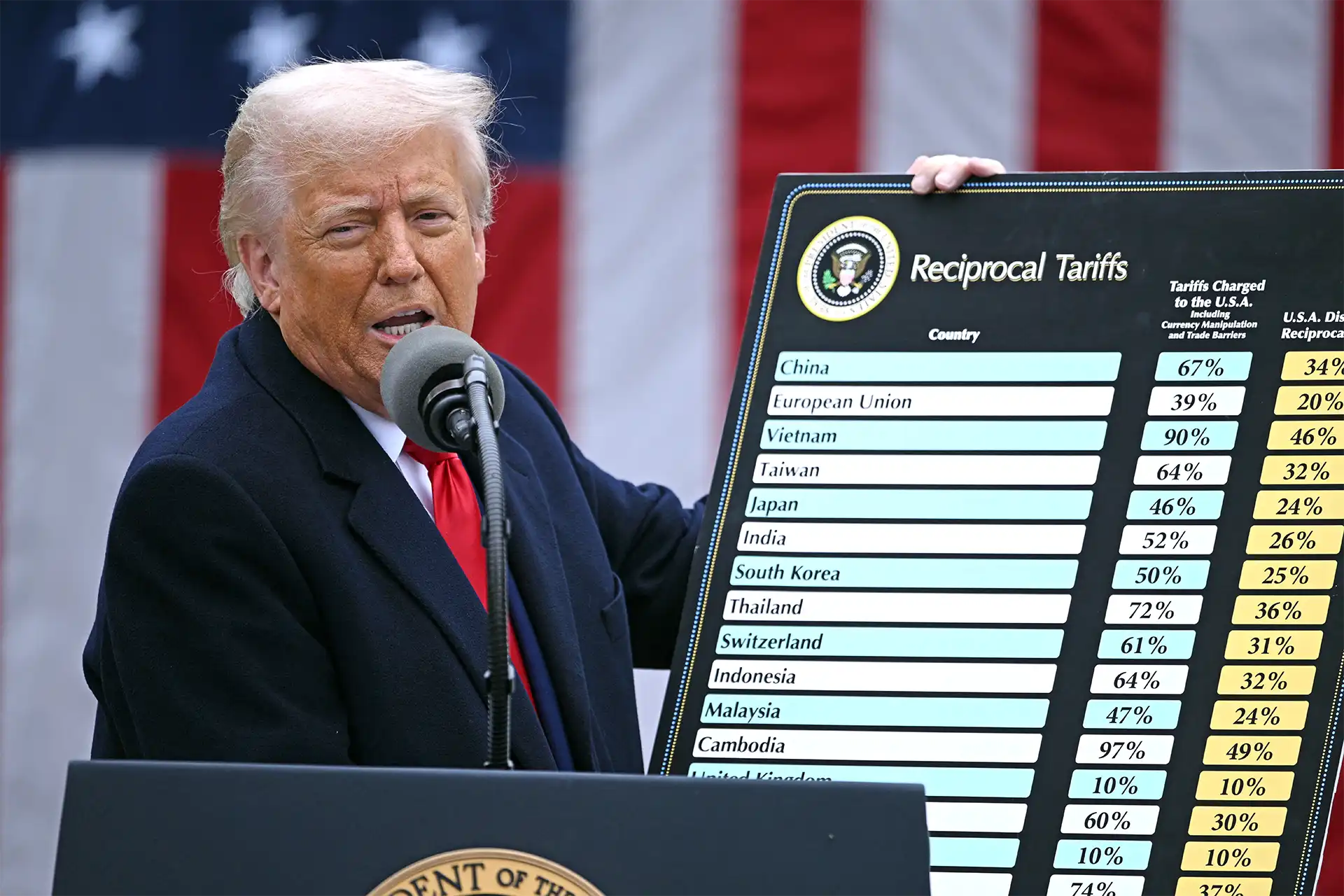

On 2 April 2025, as part of a universal tariff announcement, the United States imposed sweeping new tariffs on Vietnam, Malaysia and other Southeast Asian economies.

In justification, the US blamed these countries for circumventing existing sanctions on China.

Intended as a bold escalation of America’s strategy to economically decouple from China, the tariffs sent shockwaves through global markets and appear to have disrupted the very diversification they were meant to enhance – a diversification underpinned by the so-called ‘China Plus One’ strategy.

‘China Plus One’ – originally pursued by multinational firms and later promoted under the Biden administration – was intended to shift some factories and broader production infrastructure, both physical and digital, away from China and toward trusted partners in Southeast Asia.

The strategy also targeted supply chains – the complex networks through which goods, services, and technologies flow – as a means to reduce over-reliance on China and enhance resilience through diversification.

Ironically, the new tariffs instead undermine this effort and re-centre regional production networks around Beijing.

Rather than weakening China’s role in the regional economic order, Washington’s move exposes the fragility of ASEAN’s balancing act and inadvertently strengthens the case for China’s alternative vision of globalisation: one that is state-coordinated, infrastructure-driven, and based on different political and economic values that diverge from the US rules-based international order.

From defence to offense

‘China Plus One’ emerged in the 2010s as a hedge against rising wages, regulatory uncertainty, and, most notably, the first Trump administration’s initial tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018-2019.

While Washington framed these measures as a form of economic decoupling or ‘liberation’, Beijing did not retreat. Instead, it repurposed the logic of ‘China Plus One’ into a strategy for spreading its techno-industrial footprint across the region.

Chinese firms – including Huawei, BYD, Alibaba and ByteDance – are embedding their digital infrastructure across Southeast Asia, creating integrated ecosystems that deepen regional dependencies on Chinese platforms, standards and regulatory norms.

In short, China has gone from being decoupled from the existing digital order to being the architect of a parallel digital order.

China’s new model: Infrastructure first, norms follow

The cornerstone of China’s strategy is infrastructure. While US firms export platforms like Google, Amazon Web Services, or Facebook – often offering tools without the pipes – China delivers end-to-end systems, from 5G towers and fibre-optic cables to digital governance tools and trade agreements.

BYD’s electric vehicle facility in Thailand is not just an assembly line, it anchors a battery-to-retail supply chain.

Huawei’s cloud and 5G deployments in Indonesia and the Philippines do more than provide service – they create long-term technological dependence.

ByteDance’s AI hub in Malaysia reflects a shift from content export to ecosystem building.

Chinese companies are not just selling products, they are exporting governance models – emphasising centralised oversight, data sovereignty and coordination between the state and private companies.

As countries across the Global South adopt Chinese digital infrastructure, they also absorb China’s regulatory logic.

In doing so, Beijing is quietly influencing the future of global tech governance – not through dominance of legacy institutions such as the WTO, World Bank, or International Telecommunication Union, but by embedding its standards and practices directly into emerging digital ecosystems.

Politics & Society

Trump is no Caesar, but the republic is collapsing

ASEAN in the crossfire

The new tariffs have placed Southeast Asian states in a difficult position. On one hand, ASEAN economies have benefited from the initial wave of diversification out of China.

On the other, the new tariffs – designed to punish those seen as ‘in cahoots’ with China – expose their limited strategic autonomy in an increasingly bifurcated global economy.

What the US frames as enforcement has quickly come to be seen in the region as overreach. In practice, it punishes states for participating in regional value chains and leaves them with fewer options to grow their economies.

In this context, China’s offering – infrastructure with few conditions, regulatory consistency and long-term investment – becomes more attractive, especially in environments where rules are often volatile or politicised.

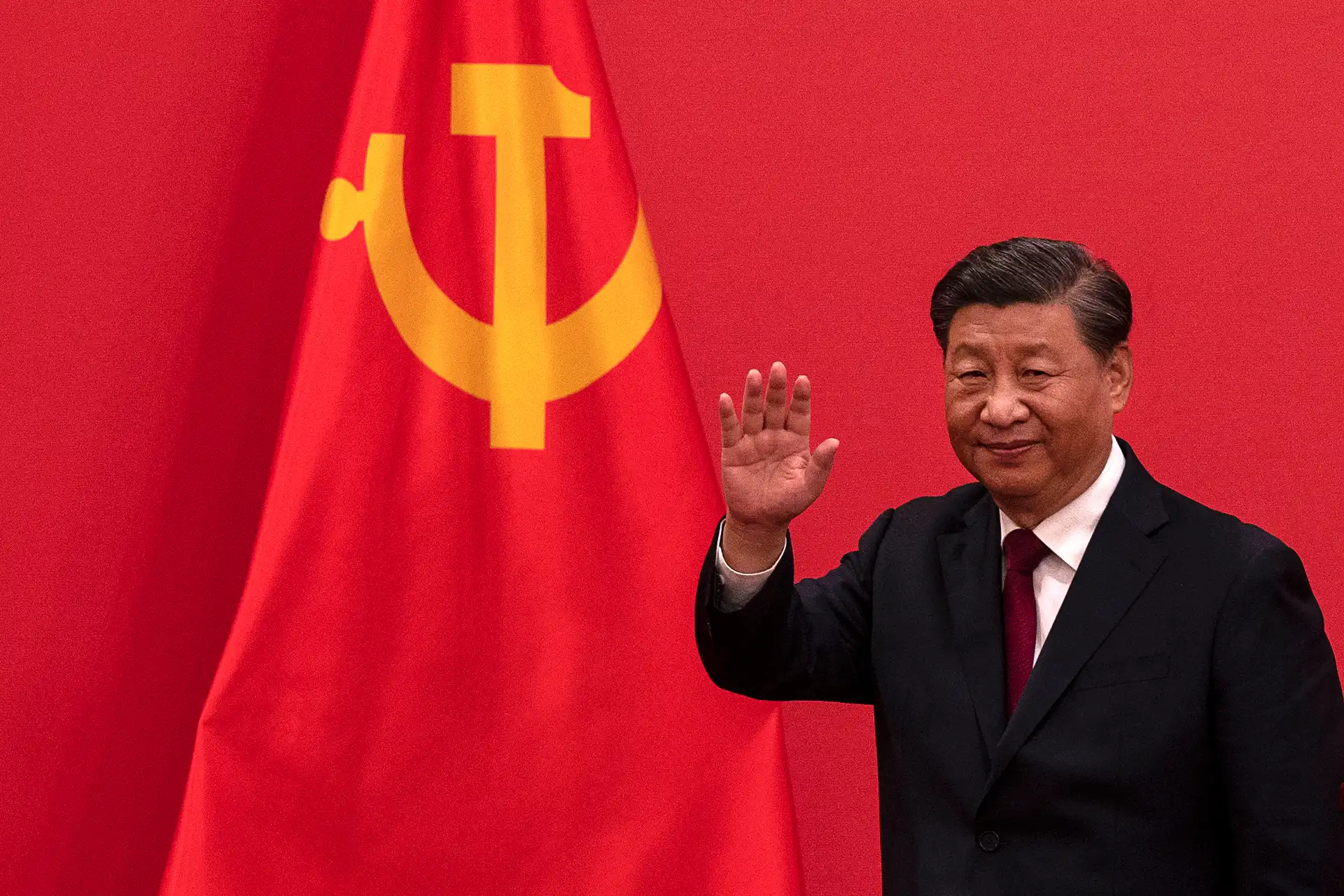

China’s diplomatic engagement reinforces this logic. President Xi Jinping’s upcoming visit to Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia is expected to reaffirm commitments to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Global Development Initiative (GDI), and the Digital Silk Road.

These visits are not merely symbolic – they are strategically timed to entrench China’s role as a regional development anchor and provider of policy alternatives, particularly as US trade pressure reshapes ASEAN’s economic calculus.

Norms at stake

The liberal economic order – once predicated on openness, neutrality and multilateral rules – is fragmenting.

As scholars Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman argue, global interdependence has become weaponised: dominant states like the US increasingly leverage their importance in global networks to exert coercive control – from tariff regimes to semiconductor bans.

Rather than fostering mutual reliance, interdependence has become a tool of strategic exclusion.

In response, China is building what Farrell and Newman term resilient sub-networks –alternative infrastructures that reduce vulnerability to Western chokepoints while advancing Beijing’s regulatory vision.

These include not only hardware and logistics, but also digital protocols, AI governance models and open-source ecosystems designed to promote sovereignty over dependency.

For many states in Southeast Asia, this model is materially viable and politically tolerable in ways that Western alternatives are not.

This is not to say China’s model is universally embraced. But in an era of systemic uncertainty, it offers a blueprint that aligns with the priorities of many developing economies: digital sovereignty, industrial upgrading and policy stability.

Business & Economics

Taxing foreigners in the land of the ‘fair go’

A New Digital Order?

If Washington’s goal was to isolate China through tariffs and sanctions, the result has been more ambiguous. In attempting to redraw the map of global production, the US has triggered a new contest against established norms – one in which China is not only defending itself but actively rewriting the rules.

Across Southeast Asia, Beijing’s presence is no longer confined to factories or ports. It is embedded in data centres, algorithmic architectures and procurement regimes.

The strategy is not simply to resist decoupling, but to rewire global connectivity on terms that reflect China’s techno-sovereign priorities.

In that sense, the April 2025 tariffs may come to be remembered not as the beginning of China’s isolation and America’s re-ascendence, but as the pivotal moment it began exporting its alternative model of digital governance – one infrastructure project, technical standard and regulatory protocol at a time.