Video games are building worlds beyond the laws of physics

Visionary architectural designs often remain unbuilt – but video games can transform these impossible structures into immersive, explorable spaces

Published 7 October 2025

Architects have long created the spaces we inhabit. They also design speculative and visionary structures that could shape our physical surroundings – ideas that often remain unbuilt.

Video games are advanced forms of media with the potential to transform these designs into immersive spaces that can be actively experienced.

It’s a common ground that links the two fields of digital game design and architecture.

Video games can ‘realise’ imaginary structures in virtual worlds.

On top of that, esoteric buildings, accessible only to a select few, transform into more tangible experiences; like the enigmatic skyscraper at 33 Thomas Street in New York City.

This skyscraper – which previously housed the US’s largest telecommunication hub and now supposedly functions as a major National Security Agency surveillance site – is inaccessible to the public.

It is a Brutalist, towering, concrete colossus with few outward openings. It feels immense, impenetrable and shrouded in mystery.

Inspired by its enigmatic exterior, the 2019 action-adventure game Control narrates a story that takes place in the headquarters of the fictional Federal Bureau of Control – what’s known as The Oldest House.

In Control, players navigate the shifting interiors of The Oldest House. It’s an exploration framed by a mysterious narrative that blurs the line between the physical reality of the building and imagined possibilities it presents.

Through the player’s immersive experience of the story and space, the game’s speculative world temporarily merges with their own, ‘real’ one.

Control is a striking example of how architecture and the built environment inspire and shape the virtual worlds of video games, and how video games can, in turn, transform these virtual spaces into an extension of our lived experience.

The prominent media scholar in the field of video game studies, Professor Henry Jenkins, describes video game designs as “narrative architecture”, saying that “game designers don’t simply tell stories; they design worlds and sculpt spaces.”

In video games, architectural structures and elements don’t just function as passive backdrops but play a central role in their storytelling.

Infusing narrative elements into spatial creations that enhance the experience is referred to as environmental storytelling.

For example, in Control, architecture operates as more than scenery; it weaves themes of science fiction, fantasy and cosmic horror into the world’s structure, motifs and elements.

The design of video game environments, worlds and architecture isn’t necessarily restricted by real-world limitations – like physics, time and space – which are traditionally at the crux of architecture.

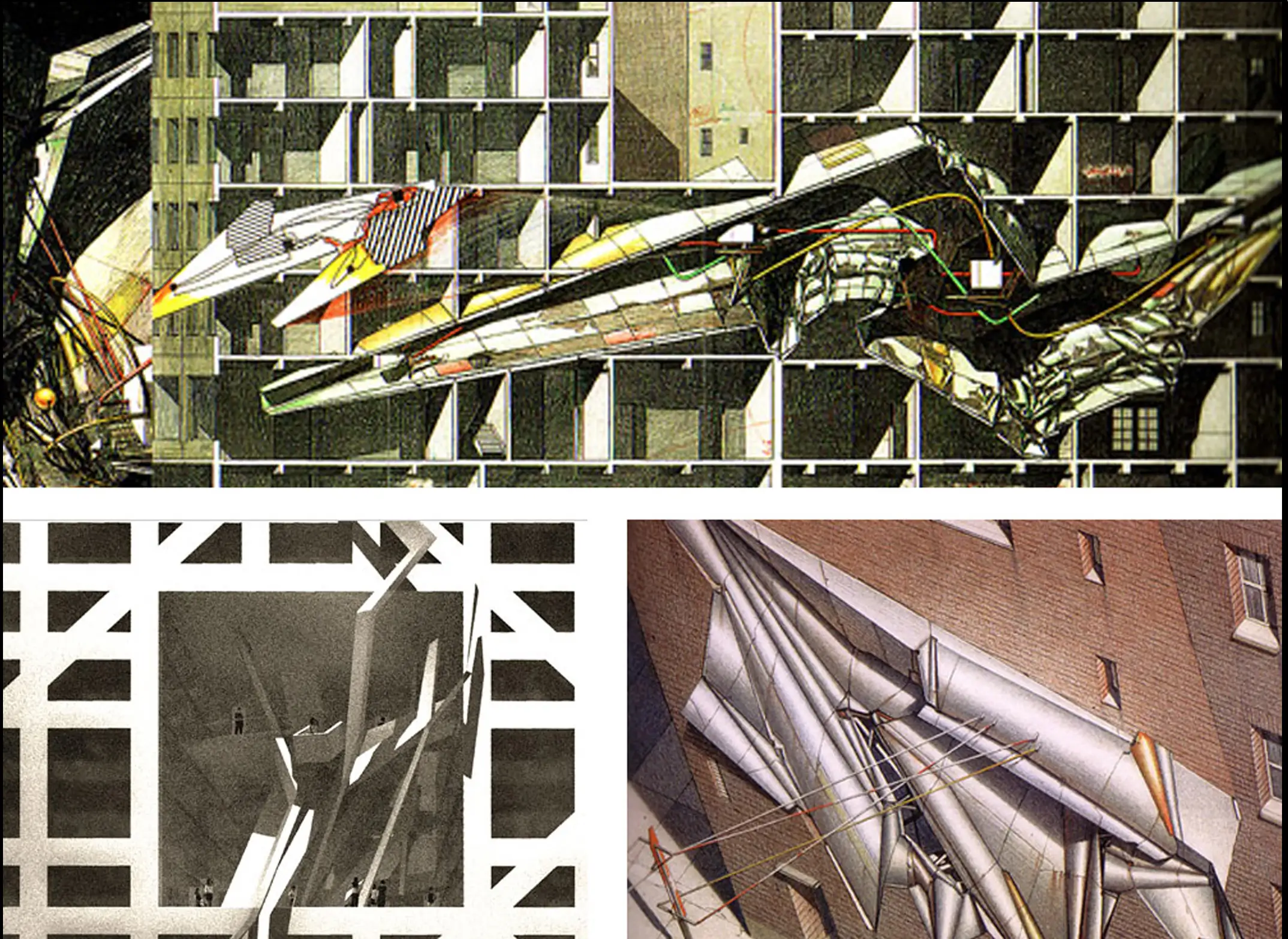

Despite these very real constraints, architects have not shied away from designing visionary, rule-breaking and reality-bending structures either.

Politics & Society

Video games combine every kind of storytelling – and invent new ones

They have long pursued imaginative and visionary works for various reasons: some to challenge existing designs, others to explore their own unique design languages and to contribute to broader architectural debates, and others to turn schools into centres of visionary discourse.

Visionary architecture is extremely diverse in its shapes, inspirations and themes.

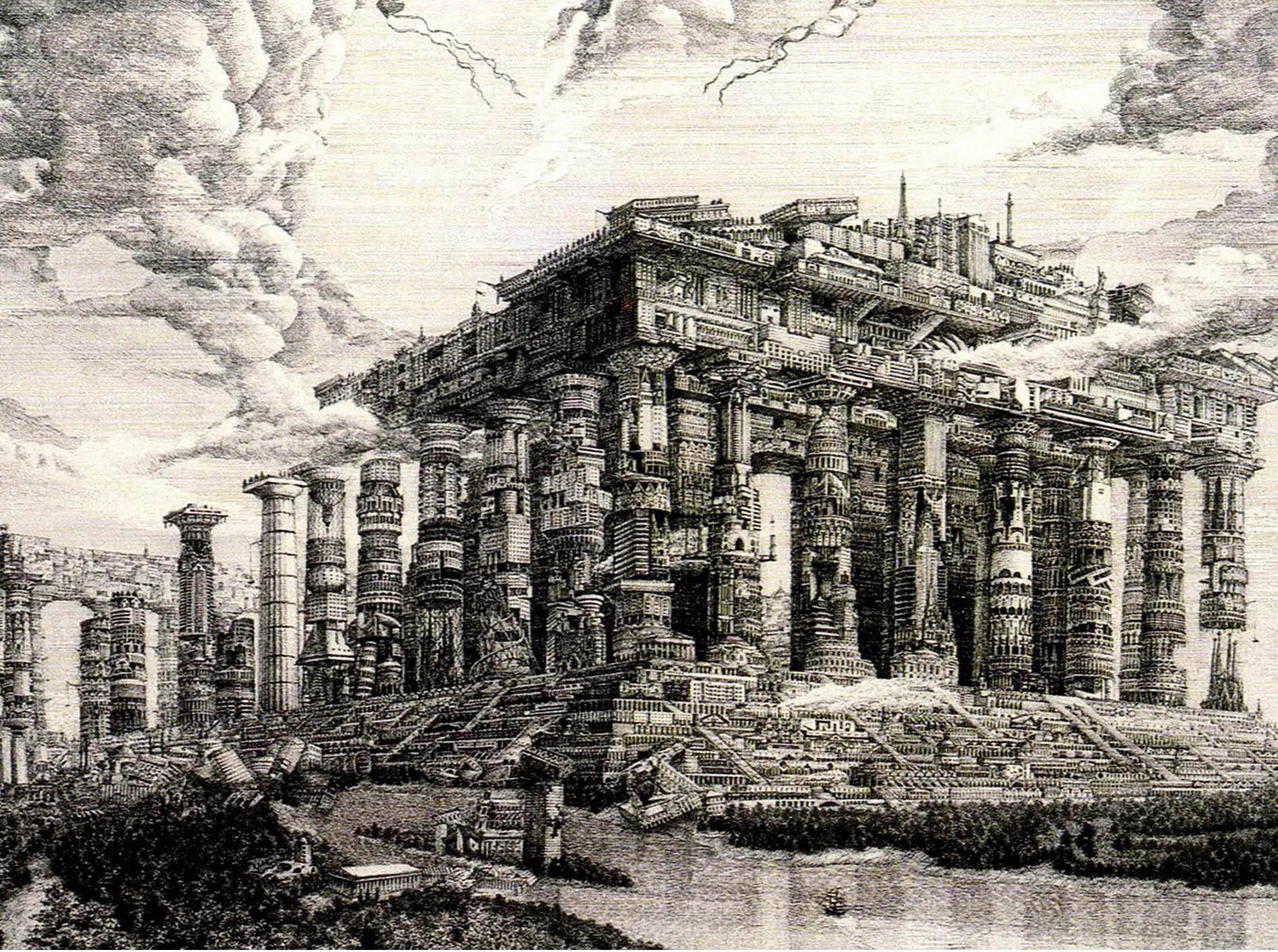

There’s the Soviet architect Iskander Galimov’s 1988 Temple City that sought to represent themes of memory, loss, and the ever-changing nature of cities.

In mid-1960s Britain, there was Archigram’s Walking City, a radically innovative design of a mobile city. Driven by the needs of an increasingly industrial society, it responded to potential threats of the Cold War.

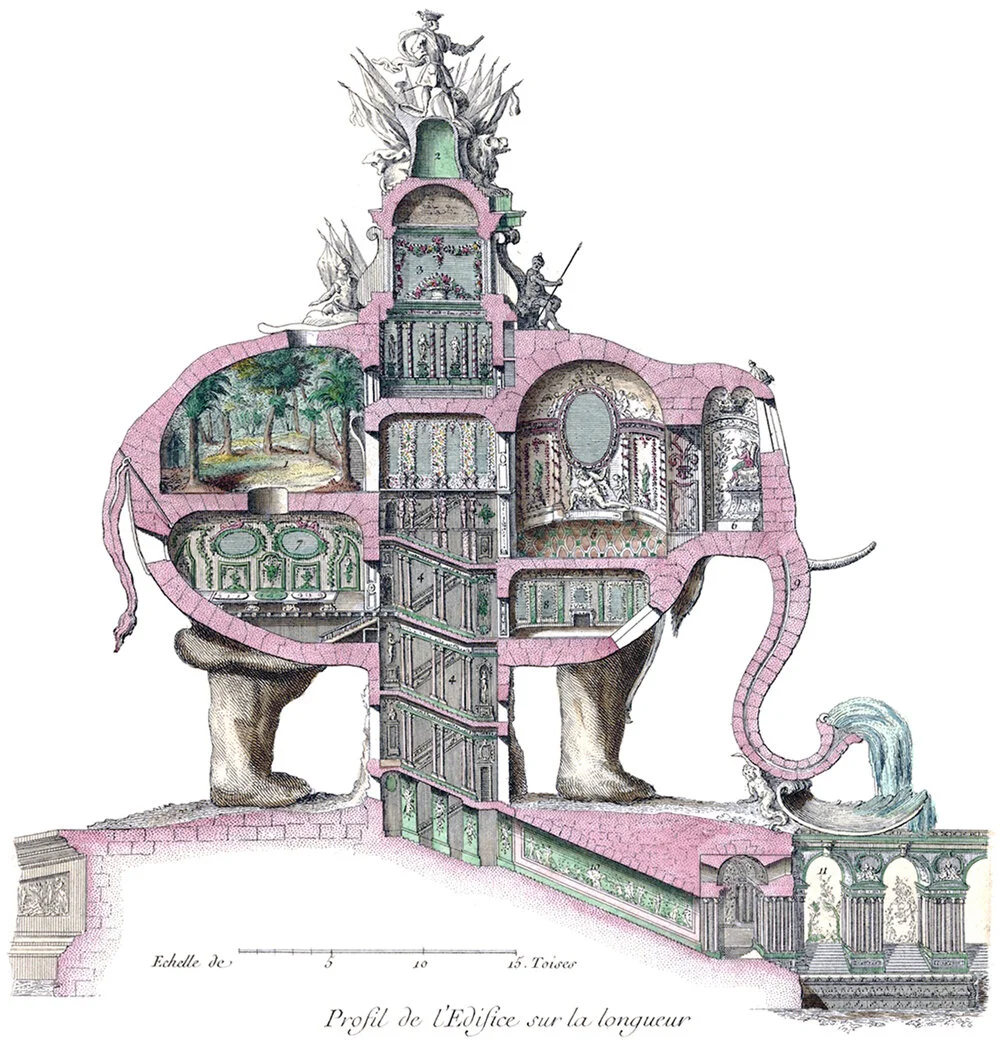

Then there’s Charles-François Ribart’s elephant monument from 1758, a proposal for a grand tribute to the French king, Louis XV, in the very heart of Paris (where the Arc de Triomphe now stands).

1 / 5

Some architectural design features direct references to objects and animals – also known as duck architecture – that catches attention while being a quirky joke in real-world design.

Despite responding to real social and political problems, many of these visionary, radical and avant-garde architectural ideas continue to be thought of as paper architecture: a “great idea, but unbuildable.”

These kinds of unreasonable structures may still have a place within video game narratives.

By bringing them to life with video game engines, these pieces of architecture could finally be interactively experienced; they can become ‘real’ in imagined, virtual settings.

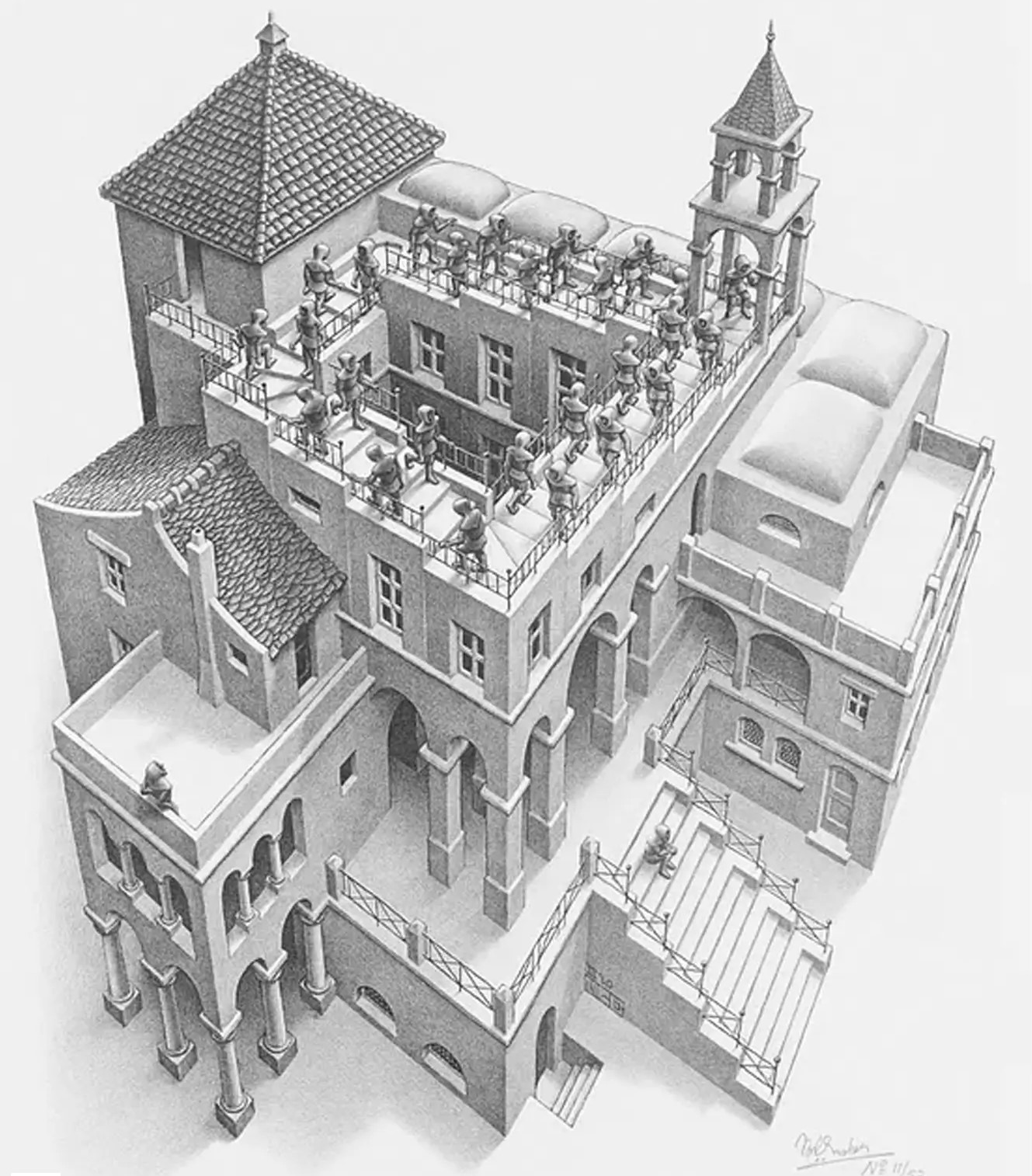

Of course, some games already incorporate ‘impossible’ architectural ideas in their virtual worlds, like Monument Valley and Manifold Gardens – both inspired by M.C. Escher’s surrealist drawings.

Video game designers, many of whom don’t have a background in architecture, may not have much awareness of these avant-garde sketches and blueprints, while architects continuously search for new tools that enable the realisation of their hypothetical designs.

A dialogue between architecture and video-game design could help fill the gaps in each field and strengthen both.