Business & Economics

Trump v Clinton: The stark choice facing the United States

Why today’s simplistic, visual culture allows a figure like Donald Trump to thrive in the US Presidential race

Published 26 April 2016

Reality television, more than any other reason, has primed us for a potential Donald Trump presidency of the United States.

Pundits look for explanations in the angry communities attracted to his xenophobic messages, a crowded primary race that has fractured mainstream Republican support for any one candidate or the increasing economic and cultural marginalisation of the American working class.

There is little doubt a combination of these factors explains his success but it steers clear of the most surprising, and perhaps the most interesting, aspect of the Trump phenomena: a reality television persona is taken as a legitimate applicant for the world’s most important job.

What about us has changed so that a reality television star is taken seriously?

A potential answer is that we now live in a visual culture that is simplified, dramatised and ideal for Trump’s brash and concept-free message.

A startling and unexplored possibility is that Trump’s success signals a significant and profound change in our sense of reality.

Business & Economics

Trump v Clinton: The stark choice facing the United States

Though politics and visual culture have always been somewhat simplified and dramatised, we live in a special age made possible by the rise of reality television and the saturation of visual communication from information-technology revolutions.

Both developments allow for a level of extraordinary simplification that blurs politics with everyday life more than ever before.

Trump’s campaign stands out from others by its deeply simplified messages that are tailored to highly simplifying technological communication.

No doubt, Trump has combined these better than other candidates, but he also benefits from a society whose reality is blurred by technologically enabled brevity and ubiquity.

Instead of fostering complex thought, something we might think both reality television and the information technological revolution would do, these mediums habituate the opposite.

The relationship between simplification and developments in visual technology goes back to the start of television.

In the 1950s, the Austrian philosopher, Gunther Anders, observed that as the television medium brought the distant world into homes, two related but paradoxical phenomena emerged: objects in great distances (glaciers, politics, exotic animals, etc) appear closer while objects near us (co-workers, pets, neighbours, etc) become more distant.

Even more than television, today’s information technology can bring visual media content from great distances and has altered our very sense of distance and reality.

Business & Economics

Unfiltered and unscripted

We can visualise Anders’ observation when we see 20-somethings absorbed in their phones texting people or looking at images from far away while ignoring the actual objects in their nearby physical environment.

That youth consider the proximity of distance normal should make us consider this phenomenon even more peculiar.

When objects from a distance show up in our homes, we begin to treat them as aspects of the world that operate under the same logic as our households or daily life. Distant places are no longer governed by different dynamics, but extensions of our own most familiar ideas. Thus the world’s complexity and epistemic doubt became diluted into a commonplace logic.

Nature is presented neatly domesticated, managing a national budget becomes akin to a family budget and international relations are understood through the morality of personal relationships.

Additionally, as one encounters the world as something processed by others for your consumption, it becomes increasingly a thing that exists to satisfy you in which you become an unwitting participant in your own narcissism.

The advent of “reality TV” in the 1990s took parts of the “regular world”, simplified and sensationalised them until they became entertainment.

Things very distant to our daily lives such as the wilderness (Survivor), high fashion (Project Runway), international modelling (Australia’s Next Top Model) or the music industry (Australian Idol) were simplified and dramatised to make them relatable to audiences.

Parts of familiar life like moving to a new city (The Real World), dating (The Fifth Wheel), courting (The Bachelor), having a family (Keeping up with the Kardashians) or buying a house (House Hunters) were given contrived twists to move them from the mundane to the entertaining.

In all of these situations, the world was made relatable because it was infused with human emotion, simplified or turned into a game.

Business & Economics

Trump: The new normal

Trump was directly a part of this media transformation through The Apprentice (2004-present). Audiences watched as corporate activities and a human resources department became a soap opera merged with a game show.

After decades of the world being made simple for our entertainment, we now have begun to think it actually is that simple.

Trump and his facile answers seem legitimate in a reality that has become increasingly abridged. The political sphere has now taken on the actual formula of simplified and dramatised reality television.

Base arguments over who has a more attractive girlfriend, whose girlfriend is slutty or genital size are strikingly similar to the “debates” on Twitter/Facebook and the personal interactions of reality television.

Arguments over policy now resemble text message as to who was a jerk last night to whom. Campaigns, like Twitter fights, are about the politics of offence, indignation and apology.

Trump, when talking about how he is winning as the chief reason he should be president, is using a circular logic that captures this US election: that the campaign’s main ethos is the campaign itself.

What happens at the rallies, i.e. who assaults whom and for what reasons, and not what the candidate talks about for the country, is a proxy for content.

In the past, when the substance of the campaigns was covered superficially, both the public and the campaigns complained. Now, the substance of the campaigns themselves is this superficiality.

Tweeting, re-tweeting and tweeting photos has taken a central role in the discourse of the election and candidate. Questions such as: Is a tweet racist? Does the tweet show Cruz’s wife to be homely? If you re-tweet are you saying it yourself?

Arts & Culture

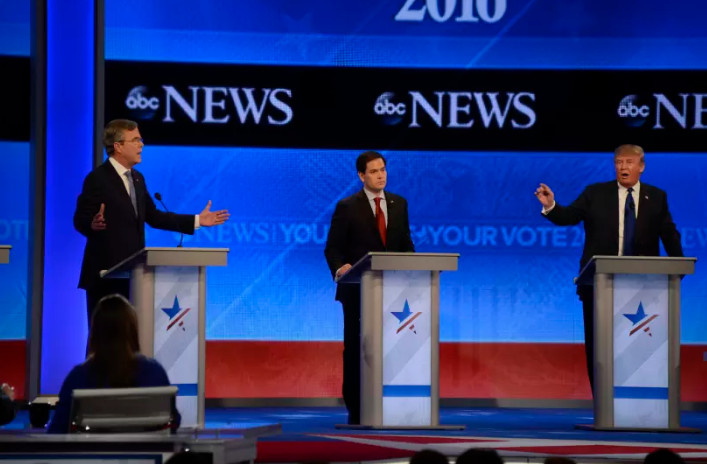

Republicans in uncharted territory

Formal debates reference what is trending on Facebook or Twitter as foundations for questions rather than research. Moderators quote Twitter and it becomes a discourse per se.

Two things follow from this new media. Content is highly truncated with only a few characters, a comment on an image or reference to a “#”.

The complexity is retracted to serve the most facile form of communication developed since the advent of symbolic communication 40,000 years ago. Simple and brash messages fit perfectly in an environment defined by parsimony and ignorance.

Banner: Flickr