Health & Medicine

Defining a pathogen

Dr Michelle Wille is studying wild birds to understand how they spread viruses across the globe

Published 16 July 2019

It is estimated that more than 99 per cent of existing viruses are yet to be discovered. But the viruses we do know the most about today are from domestic animals and humans.

In contrast, we know very little about the types of viruses found in wildlife but that is where most new viruses are predicted to originate. Importantly, some of these new viruses will have the ability to spill-over into domestic animals or humans, which is why we need to understand more about them.

My work focuses on understanding virus dynamics in wild birds because they can spread viruses over huge distances. As those viruses spread further and potentially transfer to domestic animals and humans, this can cause significant economic and public health issues.

Birds have the capacity to move viruses over huge distances because many of the viruses that infect them don’t actually make them sick.

Health & Medicine

Defining a pathogen

Some birds found on our shorelines like sandpipers spend the summer in Australia and migrate to Siberia and back each year. Gulls live in our cities and forage in wastewater treatment plants, landfills and water reservoirs.

But 70 per cent of the global biomass of birds on this planet are a single species – the domestic chicken – and occasionally, viruses from wild birds spread into poultry.

In 2005-06, the Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics estimated the gross value of production of the Australian egg industry at $340 million and the chicken meat industry at $1.4 billion, so an outbreak of disease would have a significant impact.

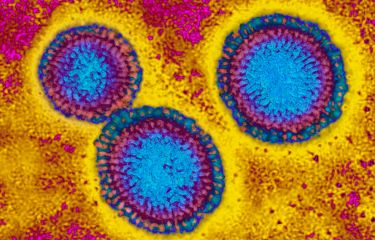

A key example of this is avian influenza A virus. A huge diversity of avian influenza A viruses are naturally found in wild birds and generally don’t cause disease.

However, detection of these viruses in poultry can be catastrophic. In 1997, a single outbreak of avian influenza in New South Wales cost almost $2.2 million and resulted in the destruction of 310,565 chickens, 1.2 million fertile chicken eggs, 261 emu chicks and 147 emu eggs.

Of greater concern is when these viruses spread from birds to people, although this is a very rare phenomenon and largely restricted to only a few strains of virus.

Bird flu H5N1 caused large global concern following a small number of human infections and over 400 billion heads of poultry were culled in response.

More worrying has been the reoccurring H7N9 ‘bird flu’ that has occurred in China each year from 2013-2018. However, large scale vaccination of chickens in China seems to have played an important role in stopping human infection in its tracks. Since the beginning of 2018, there have been almost no cases.

Health & Medicine

Our ‘killer’ cells’ role in life-long flu vaccine

By sampling Australian ducks and shorebirds, we are aiming to reveal and understand the dynamics of the many types of viruses in healthy wild birds.

Most of what we know about avian influenza in wild birds comes from studies on ducks in the Northern Hemisphere. So we have been collecting and studying samples for avian influenza surveillance in Australia to understand what drives the pattern of occurrence here.

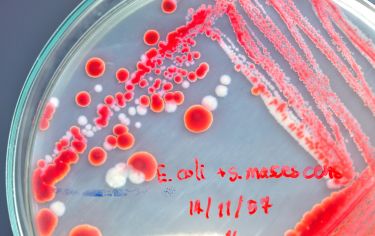

My research combines field work, lab work and computational biology. We use these techniques to work out which samples contain viruses and then try to understand the properties of those viruses.

My key collaborators for this project are Associate Professor Aeron Hurt at WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, Professor Marcel Klaassen at Deakin University and Professor Edward Holmes at the University of Sydney.

During field work we travel to different locations with the Victorian Wader Study Group to catch shorebirds. They are small but amazing athletes that migrate from Australia to Siberia and are often found along our shorelines in the summer months. We also have a program focussing on ducks.

Looking beyond influenza A, we’re investigating the whole collection of viruses in wild birds, known as the virome. This includes describing any new viruses we find and understanding which ecological factors give rise to the diversity of viruses found in birds. Recently, we demonstrated that different bird host species play different roles, where some will share virus species.

Sciences & Technology

The invisible colours protecting birds from overheating

A key factor in the diversity of viruses found in birds is whether or not they are infected by avian influenza A virus, although it doesn’t make them sick. If birds are infected with avian influenza, they tend to be infected with many more viruses so, while we cannot study viruses in isolation, the interaction between viruses is important to consider.

In our first study, we found that the Red-necked Avocet from Australia’s interior had nine different virus species and seven of those have never been described before. I could never have believed that birds could be infected with so many viruses without becoming diseased.

Overall, in our first two studies we’ve identified 52 new viral species and we expect to identify many more in the incredible, diverse world of Australian birds.

-as told to Dr Nerissa Hannink

Banner: Pink-eared Ducks, Michelle Wille