Politics & Society

Fighting to right past wrongs

Indigenous relations in Australia have come a long way, but it’s clear there is still a long and uncomfortable way to go

Published 7 July 2019

We’ve come a long way – Australia and its First Peoples.

In 1960, my Dad was born on Noongar country in southern Western Australia – the ancestral lands of my people – but back then he wasn’t counted as an Australian citizen.

Almost 60 years later, Indigenous Australians now occupy esteemed positions within Australian society, contributing greatly to our nation – senior politicians and bureaucrats like the first Indigenous Minister for Indigenous Australians, Ken Wyatt; distinguished professors in universities like Marcia Langton, Larissa Behrendt and Aileen Moreton-Robinson; talented footballers not afraid to call out the truth as they see it like Adam Goodes.

Last week I was privileged to host a panel discussion on the theme of this year’s NAIDOC week - Voice. Treaty. Truth.

On the panel were Justin Mohamed, the Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People in Victoria; Janine Mohamed; the Chief Executive Officer of the Lowitja Institute; and Mick Gooda, the Human Rights Commission’s former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner.

Politics & Society

Fighting to right past wrongs

One of key messages from our discussion was the need to focus on the obvious and persistent strengths of Indigenous peoples and cultures, rather than the deficit view that, as Justin Mohamed pointed out, too often frames Indigenous Australia.

It’s a message which resonates strongly with my own research.

My expertise is around understanding cultural connection for Indigenous youth in child protection.

As part of my PhD research, I’ve spoken to Indigenous young people about their experiences of their culture while growing up in out-of-home care. Each spoke about the importance of Indigenous identity, belonging to community and feeling pride in being Black.

Sometimes for these young people, culture was a tool that helped them combat racism, abuse, trauma and the harsh day-to-day reality of growing up in care.

But at other times, culture was peripheral, secondary to having to live in survival mode within a system that continually fails Indigenous young people.

The truth is that during the past 60 years of my father’s lifetime, we have made significant improvements in Indigenous health and wellbeing. But at the same time, Indigenous suffering and extreme poverty is an ongoing reality.

The fact is our Indigenous child protection rates are getting worse, not better.

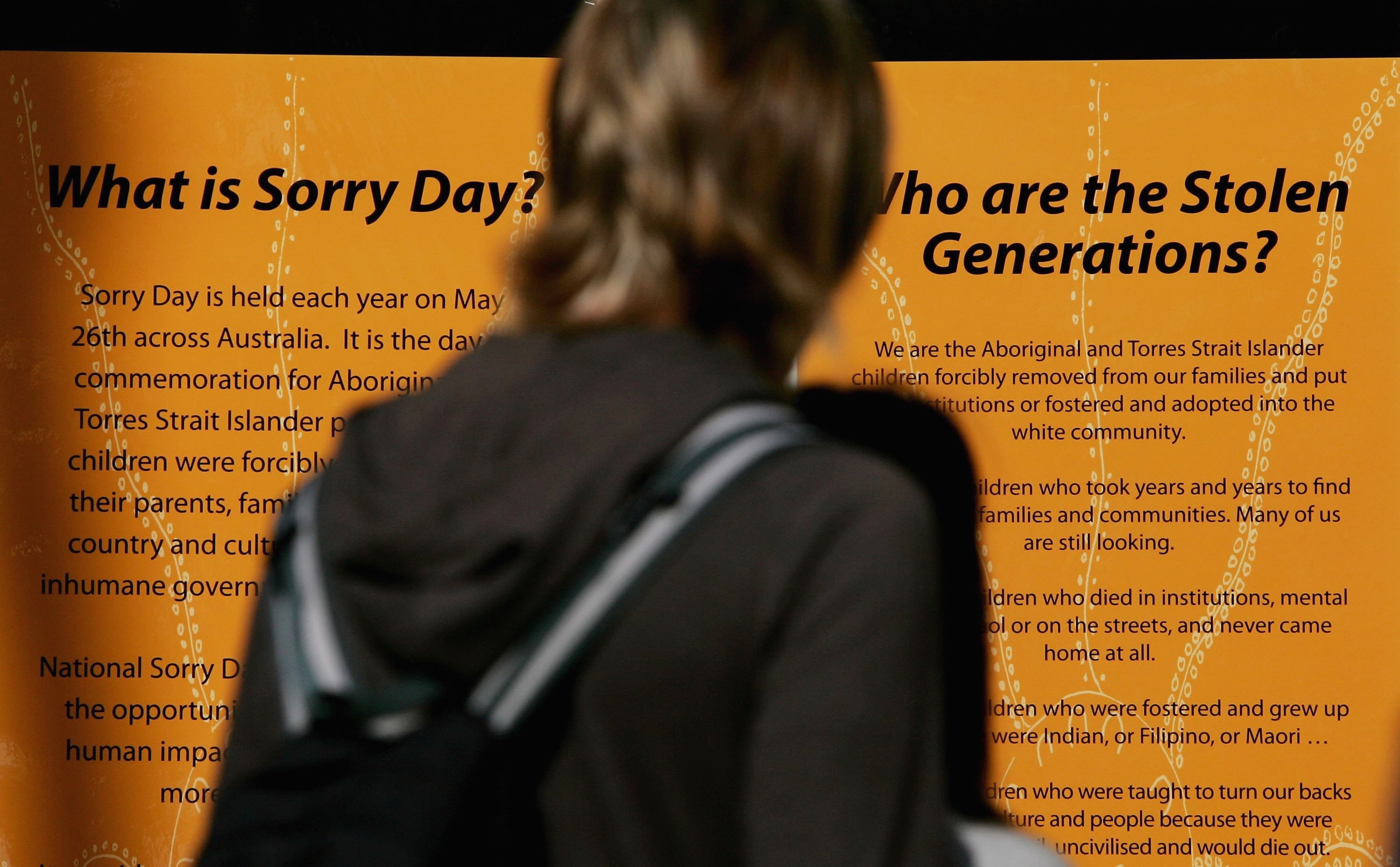

There are more Indigenous children being removed from their families now than there were during the Stolen Generations. Indigenous incarceration is getting worse.

Politics & Society

Grounded in truth

We only need to look at high-profile cases like the 2014 death in custody of Yamatji woman, Ms Dhu, to see that jail is used too readily to punish petty offences like unpaid fines instead of seeking alternative justice solutions.

And Indigenous suicide? It’s at a crisis level, with 62 Indigenous people, mostly young, having already taken their lives in 2019, just six months into the year.

Yet, the major reason for the suicide crisis and the increasing child removals, is poverty, and poverty is preventable if governments have the right policies and invest in better social assistance for vulnerable Australians.

Many of us are familiar with the rising cost of living in Australia. Melbourne, my home on Wurundjeri country, is an increasingly unaffordable city.

But imagine trying to survive on a Newstart budget of $A601.10 per fortnight as a young 20-year-old single mother in Victoria, while also dealing with unstable housing, family violence, the trauma of past suicide attempts and child protection taking you away from your family.

That was just one of the stories told to me by a young person I spoke to for my research, and there are countless similar stories of struggle, poverty and suffering told by Indigenous peoples in communities throughout Australia.

The truth is ugly and, as Janine Mohammed told the audience, uncomfortable.

That’s why in 2019, we’re still calling out for historical and contemporary truths about Indigenous Australians to be told, heard, accepted and acknowledged.

Politics & Society

Going beyond healing to build Indigenous power

As a nation, Australians are quite capable of owning up to personal wrongdoings, but when it comes to collective wrongdoings, we much prefer to sweep it under the rug or blame someone else.

A case in point is former Prime Minister John Howard’s refusal to apologise to the survivors of the Stolen Generations.

Instead, he asserted that the current generation of Australians were not responsible for historical wrong doings.

Individually, yes, many Australians in 1997 (when the Bringing them Home report was released) were not directly responsible for the Stolen Generations.

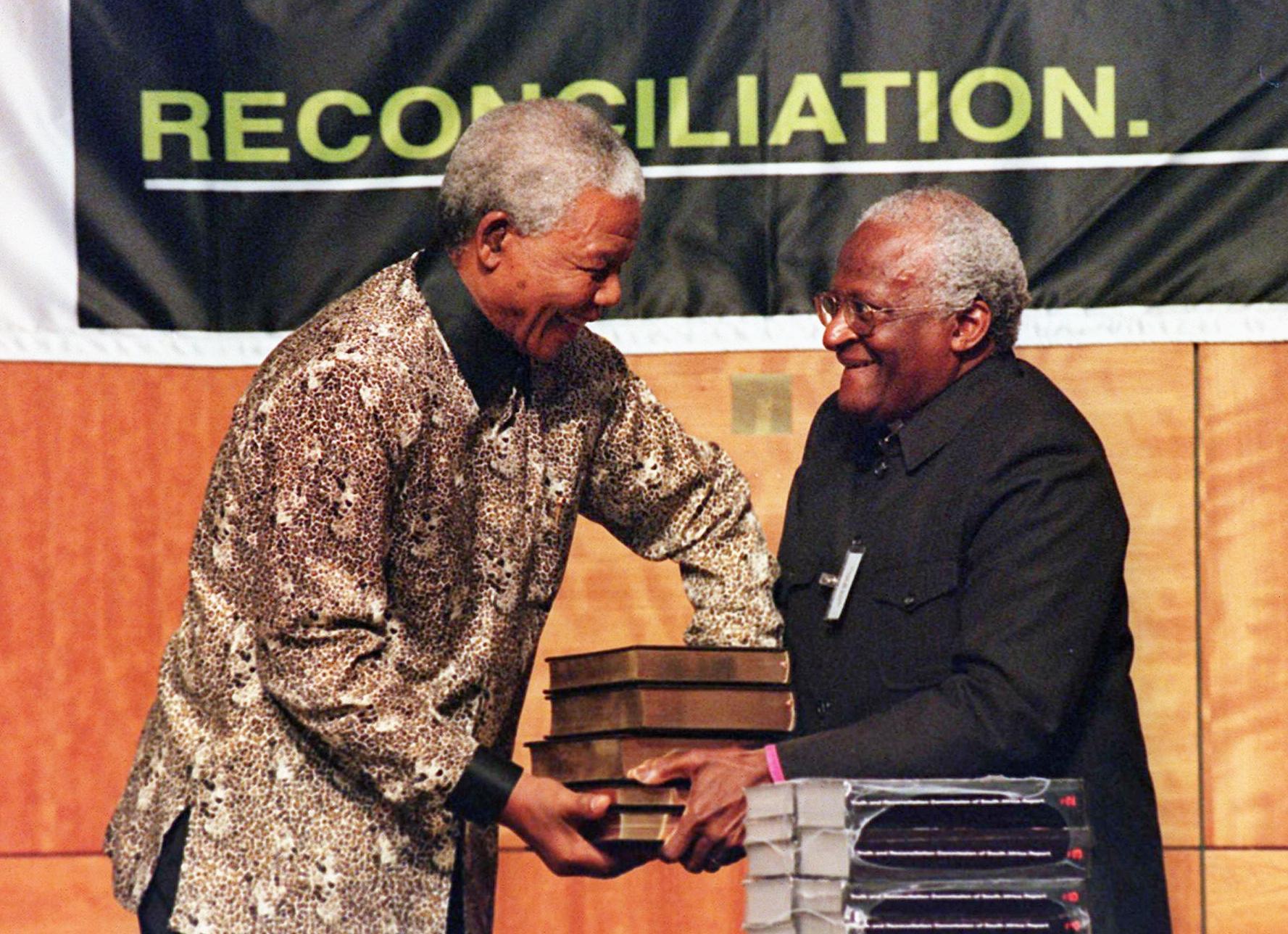

But collectively, we are, as a nation, responsible for owning and accepting our history – the good, the bad and the ugly – just as other nations around the world, like Germany and South Africa, have owned their histories and their complicities in gross human rights violations.

Here in Australia, we’re still reluctant to confront our truth. Australia is the only first-world country to not have a treaty with its Indigenous peoples.

We were one of the last signatories of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and, our human rights record around the treatment of our Indigenous peoples has been called into question on the international stage several times.

While efforts towards Constitutional Reform have silently disappeared from the conversation.

Our federal election in mid 2019 strangely skipped any conversations about Indigenous affairs.

Victoria is in treaty conversations with First Nations traditional owners, but at a Commonwealth level, treaty conversations and the call for a Makarrata in the Uluru Statement from the Heart have been rejected.

Health & Medicine

Backing the strengths of Aboriginal young people

We’ve come a long way, but we have much further to go.

Part of the conversation we had during the panel discussion was a consideration of national identity, collective ownership of our past and the education of our nation about historical wrongdoings committed against First Nations Australians.

Grassroots activism – like that of the strong Black women who lead the Grandmothers Against Removals campaign to fight against continued Indigenous child removal – demonstrate that our voices are strong.

It also demonstrates that self-determination and Indigenous-led solutions are best sourced on the ground by the communities who know the issues best.

However, we also need all Australians to listen when we call out the truth.

Meaningful change for First Nations communities requires an Australian imagination where all Australians – from government to Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities – support movements to tell the truth and own our nation’s Black history.

As Mick Gooda articulated during his panel speech, accepting the truth doesn’t mean that we don’t lose our national identity. Instead, we – as a nation – gain more than 65,000 years of rich Black history to be proud of.

And that’s a truth that will collectively set us free.

Banner: Tracey Nearmy/Getty Images