Sciences & Technology

From grapevine waste to a sustainable building material

New technology that can convert human urine into fertiliser onsite could enable an expansion of urban farming and eventually provide a sustainable resource for agriculture

Published 10 August 2021

Imagine a future where the flush of a toilet could contribute to sustainable food production.

Human urine accounts for around one per cent of the sewage flow in Australia, but it also carries about 80 per cent of the waste nitrogen and 50 per cent of the waste phosphorus in our sewage – both important elements for plant fertilisers.

Humans excrete about 10 grams of nitrogen and 1 gram of phosphorus daily. For cities like Melbourne or Sydney that is about 50 tonnes of nitrogen and 5 tonnes of phosphorus a day, or about 25 per cent of the daily fertiliser requirement for food production consumed locally (about 250 tonnes of nitrogen).

Simply treating urine as a waste product then is a huge missed opportunity, especially at a time when the growth of global populations will make fertilisers increasingly important to sustain food production.

Sciences & Technology

From grapevine waste to a sustainable building material

In addition, there are challenges with traditional sources of commercial fertiliser. Nitrogen fertiliser (ammonia) is produced from natural gas and is energy-intensive – accounting for two per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Phosphorus meanwhile is mined from rock and is a limited resource. It is estimated that current economically viable reserves of phosphorus amount to less than 100 years of supply, suggesting the cost of mining phosphorus is only going to rise.

This is why University of Melbourne chemical engineering researcher Dr Stefano Freguia and his team want to install electro-bioreactors in the basements of newly built office buildings and apartment towers that can separate out the phosphorus and nitrogen to create fertiliser on site.

As it’s all done in the electro-bioreactor, antibiotics, drugs, viruses, diseases and other undesired contaminants in our urine are either biodegraded in the bio-reactor or flow out with the waste urine.

“The idea is to create a circular economy of nutrients in Australia by re-using human urine as a source of fertiliser that could initially feed the growth of urban farming like hydroponics, but also ultimately supply broadacre agriculture,” says Dr Freguia.

Sewage treatment plants already strip out nitrogen from waste like urine – most of it is then converted back to gas – however, the technology is costly and energy-intensive. The existing infrastructure is also near capacity, says Dr Freguia, and new centralised infrastructure will be not only expensive but also unable to deliver the flexibility that is needed in the fast-changing urban landscape.

Health & Medicine

The impact of air pollution on life expectancy

Dr Freguia says on-site bioreactors could solve both the need for new (renewable) sources of fertiliser and the sewage treatment challenges.

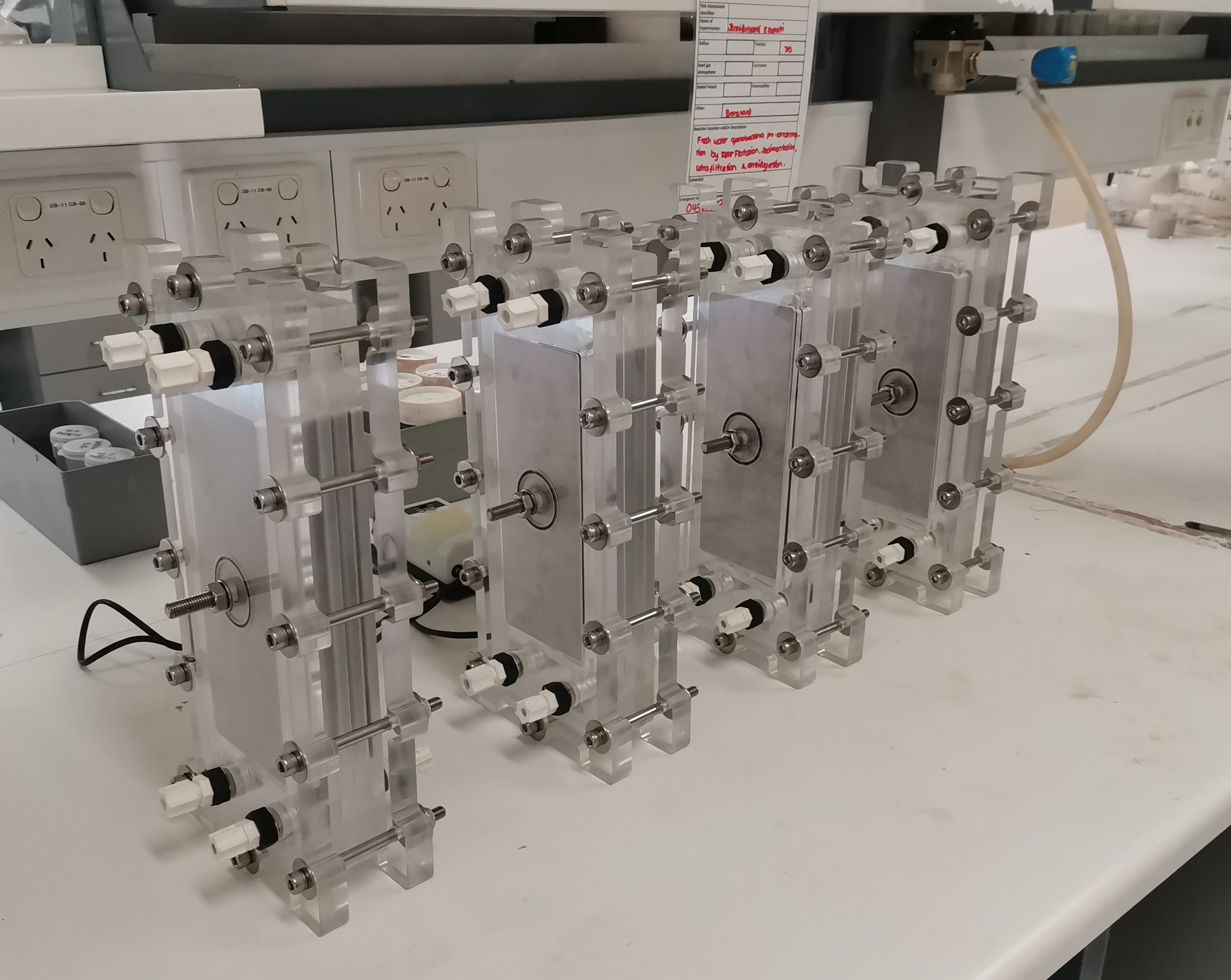

The bioreactors use a process called electrolysis where power is used to strip out nitrogen, phosphorous and other nutrients from the urine by propelling them through the tiny pores of specialised membranes. The treated urine can then be put into the sewage system while the nutrients are used as fertiliser feedstock.

But rather than using external electricity to drive the electrolysis, Dr Freguia has developed a technology that uses the chemical energy held within the urine which is released by special microbes, creating bio-electricity. In this way the process is self-sustaining.

“Previous proposals for nutrient recovery from urine have used high energy consumption and chemical inputs, so the addition of low energy consumption and energy footprint technology makes this project more viable on a large scale,” says Dr Freguia.

The technology was first tested by Dr Freguia’s group when he was at the University of Queensland and is now being modified at the University of Melbourne in readiness for larger-scale testing.

It will be pilot tested in a public park in Brisbane to make fertiliser from the urine of 300 people every day, as part of a new Industry Transformation Research Hub named Nutrients in a Circular Economy (NiCE) that recently secured more than $A2 million in funding from the Australian Research Council.

Sciences & Technology

Are robots the answer for aged care during pandemics?

NiCE is a collaboration between the University of Technology, Sydney and the University of Melbourne, and is led by UTS’ Professor Ho Kyong Shon.

Ahead of the Brisbane pilot, a smaller scale system will be installed in the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology on the Parkville campus.

The electrolysis process creates a concentrated product that reduces the cost of transporting it for use. So far in successful lab testing about 100 litres of urine yields around 10 litres of fertiliser, and Dr Freguia believes his team can further concentrate it as the process is scaled up.

If the composition is not ideally suited for a given crop, then the concentrated product may be blended or amended with other fertilisers.

A key challenge is to work out how to harvest the urine at the toilet site. Men’s urinals are easy as they can simply be diverted to the bioreactor, and that is what is planned at the University of Melbourne trial.

However, pedestal toilets present a problem in separating urine from faeces. In Europe, there are already specially-designed pedestal toilets with innovations including a delayed flush so the urine is drained first before the solid waste is flushed.

Health & Medicine

Do you think better when you’re moving?

There are also social factors that need to be addressed, including societal views and values that make people reluctant to use human waste as a source of fertiliser. A key group to work with will be the farmers using the product.

“Ultimately for the circular nutrient economy to become reality in Australia, social acceptance of these alternative toilets and urine collection systems will be required,” says Dr Freguia.

Accordingly, the researchers are planning an education program to engage with the public.

“It will need people to think differently about urine, but I don’t think that will be too difficult. After all, what we are doing is making it really easy for everyone to help the environment and sustainability.

“You can make our future greener with the simple act of urinating.”

Banner: Getty Images