Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

Feeling unsettled? We’re living through the consequences of a culture of disruption that’s been centuries in the making

Published 2 April 2025

Over the course of history, human societies have relied on cultural traditions, religion, laws, moral frameworks, social structures and processes of governance to deliver predictability.

Predictability is what allows us to form societies, produce food and great works of art, and discover new knowledge about ourselves and the world.

Against this culture of predictability there arose, in European societies beginning in the late 17th century, a counterculture of disruption.

The Enlightenment and the scientific revolution in Europe were intellectual movements directed against tradition and ancient knowledge systems.

Since Galileo, the ethos of science has been to prove existing knowledge either wrong or incomplete.

Rational thought became the source of authority, rather than appeals to divine will or religious texts or aristocratic privilege.

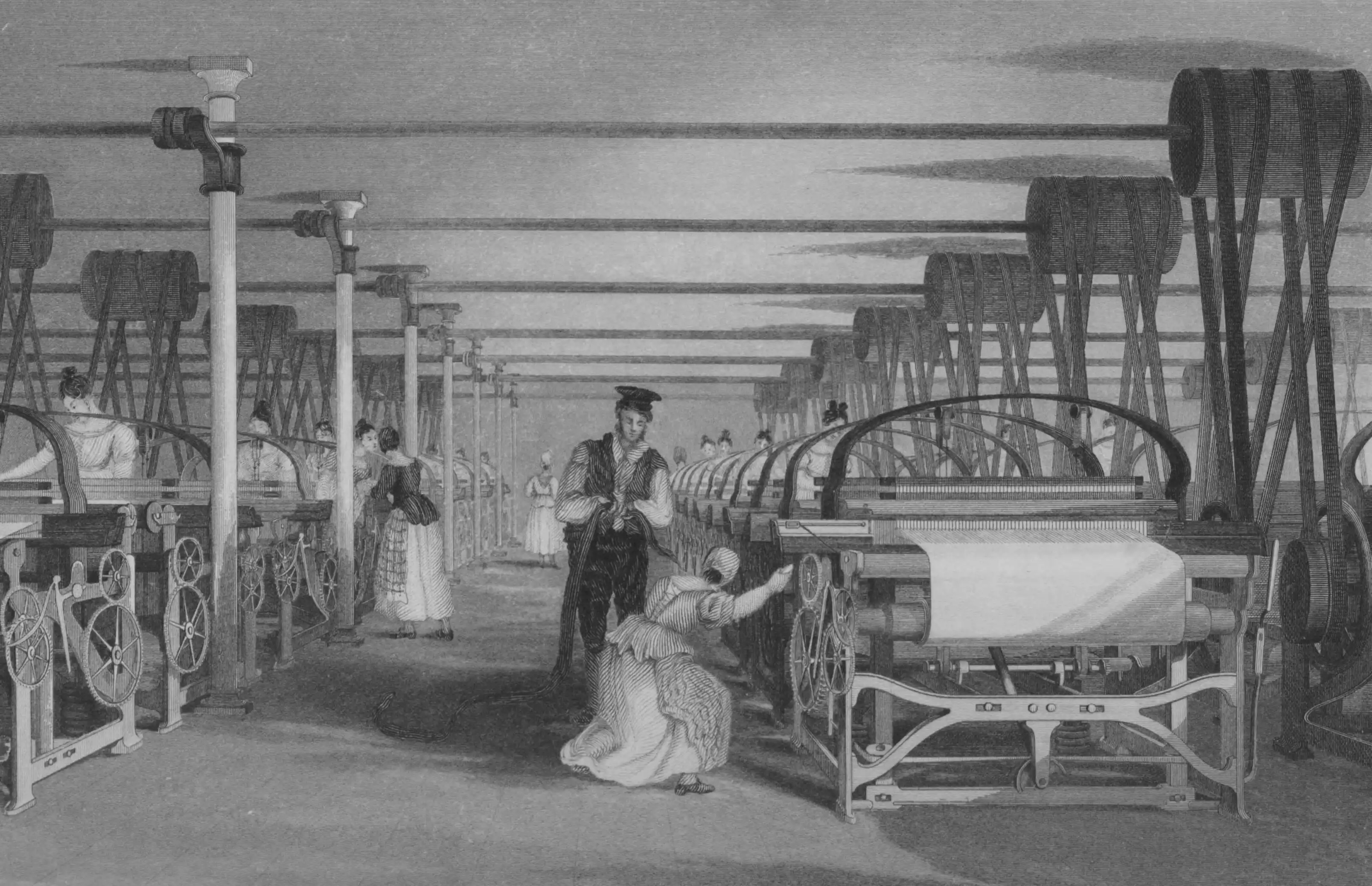

At around the same time, capitalism and industrialisation got underway, bringing a culture of disruption to economic life.

Politics & Society

Your social media feed is changing democracy

New systems of credit and insurance enabled much greater commercial enterprise, often spanning the globe.

New sources of wealth upended traditional social structures, sponsored new movements in art and architecture and drove realignments in national and international politics.

New, mechanised forms of production and transport displaced older, craft guild-based modes of production; revolutions in agriculture depopulated rural communities and gave rise to great cities.

Technology is another great disruptor. Invention, innovation and applying science to production drove successive waves of industrial revolutions.

Then there has been culture. From the late 19th century there developed in the West pervasive critiques of the optimistic narratives of human improvement.

Literature, music and films returned ever more insistently to the negative impulses of human nature; language increasingly reflected the idiom of the street gang.

Each of these six vectors of disruption are reinforcing; each borrows from the others in its endless search for further disruption.

Taken together, they all contribute to a generalised culture of disruption, where disruption is viewed positively rather than negatively; where disruption is seen as what’s right with society rather than a sign that society has it wrong.

‘Disruptive technologies’, ‘moving fast and breaking things’, ‘the next revolution’ are the new ethos.

The new titans (so many of them now crowding around the Trump administration) are lauded because of both the depth (how completely the new upends the old ways of operating) and the breadth (how many aspects of life are redefined by the new) of their disruptiveness.

Discussion & Debate

‘I am watching the US enthusiastically leap into an authoritarian regime’

The key questions are whether the culture of disruption is here to stay. If so, does this mean the systems of predictability, continuity and certainty that have been developed and protected in all societies for centuries will be discarded?

I think there are three realms where culture of disruption is taking hold and making huge inroads into our institutions and systems.

The first is in politics and geopolitics. In this realm we see the rise of ‘transgressive politics’.

Transgressive politics is a form of political dominance that arises from breaking the accepted rules, norms and expectations of politics and geopolitics.

It both draws from and feeds growing public disgust with conventional politics and politicians and the spreading sense that existing institutions are broken and incapable of delivering on what is needed.

The transgressive politician casts conventional politicians who abide by the rules and conventions as insincere and phony; while he (and so far, they have all been men) is authentic because he breaks the rules.

Transgressive politics is a high-wire act.

The politician who transgresses and survives to grow in popularity has demonstrated his strength, his ability to surpass the rules, his uniqueness and his calling.

Transgressive politics translates to transgressive geopolitics very smoothly.

A leader who does not abide by domestic institutions and norms will also likely ignore international norms and institutions.

Accepted international boundaries are up for being redrawn; long-standing allies are humiliated and intimidated; liberal regimes of global trade and investment upended.

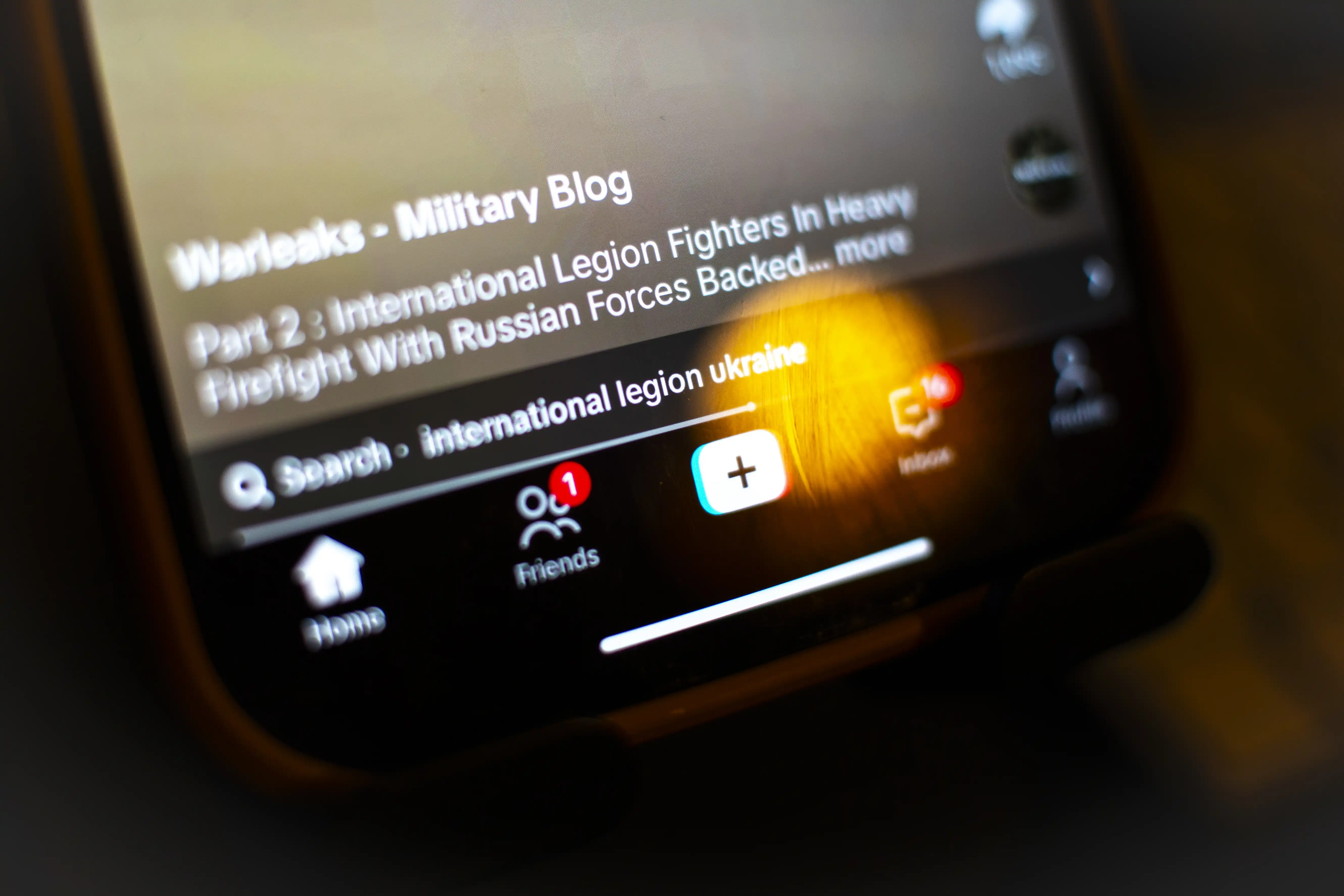

The second realm that concerns me is technology. In particular, the combination of the internet, social media and smart phones.

This trinity of technology gives people access to a massive lake of information – greater than ever available to humans in history.

The web provides information that’s separate from any form of authoritative verification or quality control, allowing people literally to choose their own facts and to dispute the facts of others.

Our advancing tech also provides us with an unprecedented capability to connect to others, irrespective of time and space.

The first quarter of this century has seen a surge in extreme beliefs and political polarisation; a questioning of authoritative knowledge and expertise; and further declines in actual sociability.

And there are other more subtle effects.

The constant scrolling we do on the web, social media and our smart phones has seen a dramatic decline in human contemplation as algorithms serve up serial dopamine hits to inert brains.

Reading has declined, as a new generation fails to develop the concentration and imagination to read extended texts.

More generally, the rise in scepticism, find-your-own-facts and suspicion of expertise is hollowing out the institutions that once generated social cohesion in our societies.

Business & Economics

Trump, tariffs and the implications for Australian supply chains

This has led to a collapse in trust in the institutions that once provided the unifying feelings that held society together: government, churches, the media and universities.

The third realm is climate change – as humanity seems to be sleepwalking towards disaster.

It’s the global challenge that has most revealed what a weak reed is multilateralism in the face of diverging national interests.

I once thought that competition to lead the renewable energy transition between the US, Europe and China was a positive development.

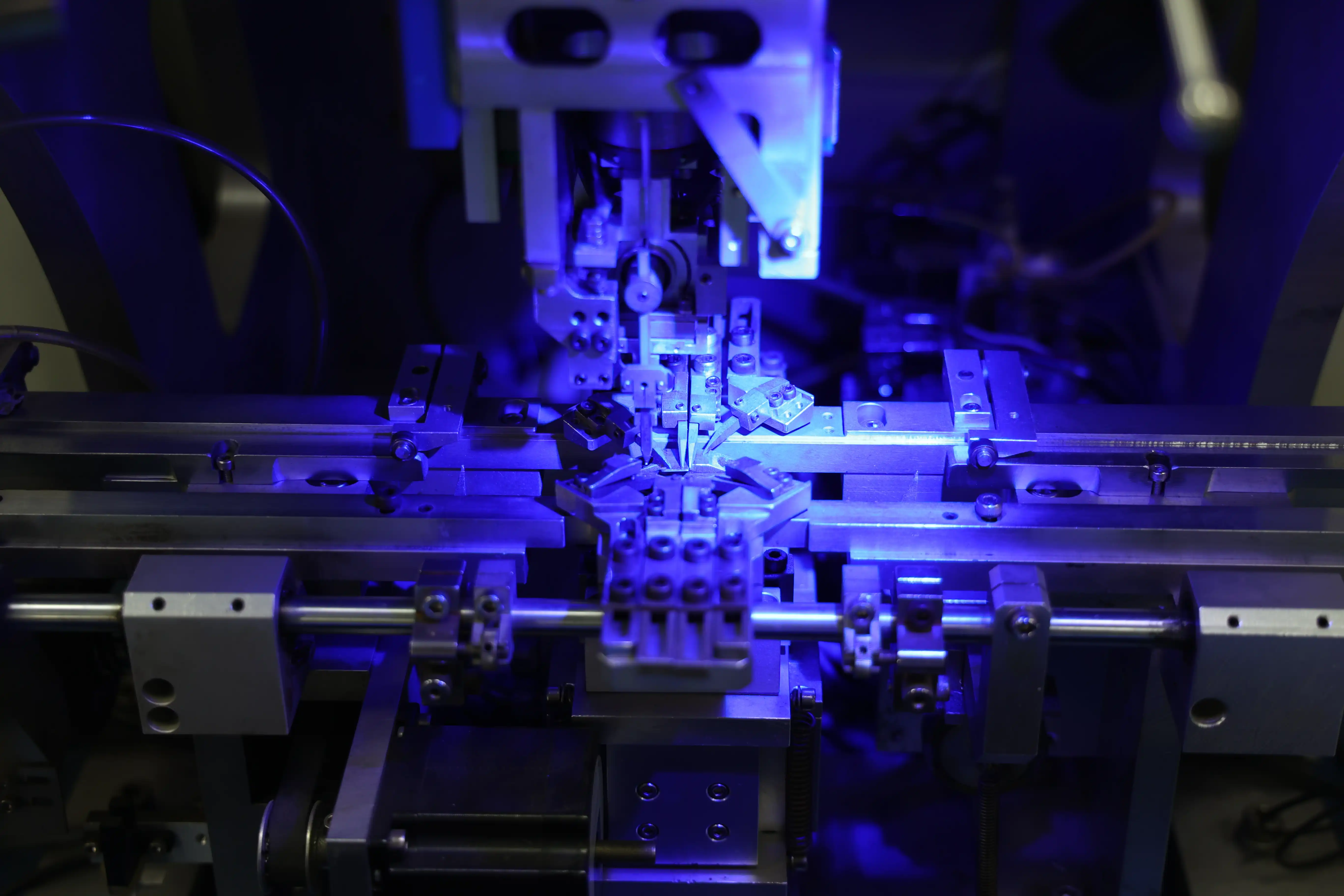

No more: the competition, particularly between the US and China, has entered a phase in which rather than competing to develop better technology, they have entered a phase of trying to restrain their rival.

The US restrictions on China’s import of advanced microchips, and China’s retaliatory restriction on exports of rare earth minerals to the US, will have a net effect of restraining progress towards the energy transition

The headlong race for disruptive energy technologies has acquired a geopolitical edge that is starting to obscure the actual rationale of the energy transition.

Internally, climate change is playing into the disruptive politics of many nations, as societies begin to polarise over whether climate change is occurring – and what might be causing it.

Arguably, the climate wars have been the cause of the greatest surge in anti-elite, anti-expertise sentiment in western societies.

They have given rise to extremism on both sides of the debate: renewables fundamentalism on one side, fossil fuels ranting on the other.

The casualty here is pragmatism, steadiness of purpose and a single-minded determination to mitigate the problem.

We have also started to see another form of internal division: between different regions of the same country.

In the US, states that are particularly prone to the effects of climate change, including California and Hawai’i, are strongly pro-climate action; while those that benefit economically from fossil fuels production, like Texas and Wyoming, are strongly anti-climate action.

The same seems to be happening in Australia, pitting pro-climate action Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia against anti-climate action Queensland and Western Australia.

The culture of disruption, as we’ve seen, has been centuries in the making.

What is recent is the effect that the culture of disruption is having on politics and geopolitics, technology and society, and climate change in the 21st century.

I would challenge anyone to nominate another historical period when the disruptions to our basic social institutions of predictability and social solidarity have been eroded as they have in the past 25 years.

The effects of these disruptions are everywhere, spoken about individually but rarely brought together and discussed in relation to their common causes.

When we react in horror to the rise of hate speech, the spread of incivility, the culture of corporate greed with regulations here, inquiries there – we are tinkering at the edges of a large and spreading problem – the relentless erosion of the institutions and practices that provide predictability and social cohesion.

Health & Medicine

Is rising inequality fuelling our moral outrage?

It is time to have a larger conversation about how we start re-investing in those institutions and practices.

On the one hand, the institutions that once provided predictability, authority and cohesion, need to rediscover their purpose: objectivity, not invective; respectful debate, not denunciation of opposing views.

And if those institutions that once provided predictability and cohesion are hopelessly compromised, we need to develop new institutions that can play that role, in the face of the relentless onslaught of disruption.

This is an edited extract of Professor Michael Wesley’s speech to the National University of Samoa on 30 January, 2025.