What does strong political leadership in Australia look like?

The new McKinnon Prize in Political Leadership aims to recognise political leaders who have driven positive change and encouraged a national discussion about the role of leadership

Published 5 December 2017

It began with a chat over coffee in Carlton and culminated in a phone call 12 months ago that might be the catalyst for a new national conversation about political leadership in Australia.

Melbourne businessman, Grant Rule, was on the tarmac at Los Angeles International Airport, about to head home after meetings with private equity firms, when he took a call from Nick Reece, who was Julia Gillard’s key strategist for a time during her prime ministership.

Mr Rule had initiated the contact several months earlier, cashed-up and keen to discuss ways to encourage a new kind of politics, one that was less adversarial and negative, and more about making the country a better place.

Nick Reece was receptive, having embarked on a new career that included being a principal fellow at the University of Melbourne’s School of Government.

What Grant wanted was ideas on how to lift the standard of political leadership and encourage people outside politics to consider offering themselves for public office. At a time when public esteem for politicians had reached a new low-water mark, what Mr Reece proposed was counter intuitive.

“What about a prize for political leadership?” he suggested.

After all, virtually every other field of endeavour has a prize for excellence or a means of celebrating success. Think the Brownlow, the Archibald, the Dally M, the Walkleys, the Logies.

“I love that idea!” came the reply. “We’d love to support it.”

This is the story behind the McKinnon Prize in Political Leadership, a collaboration between the University of Melbourne and the Susan McKinnon Foundation, a non-partisan philanthropic organisation set up by Grant and his wife, Sophie Oh, in 2015.

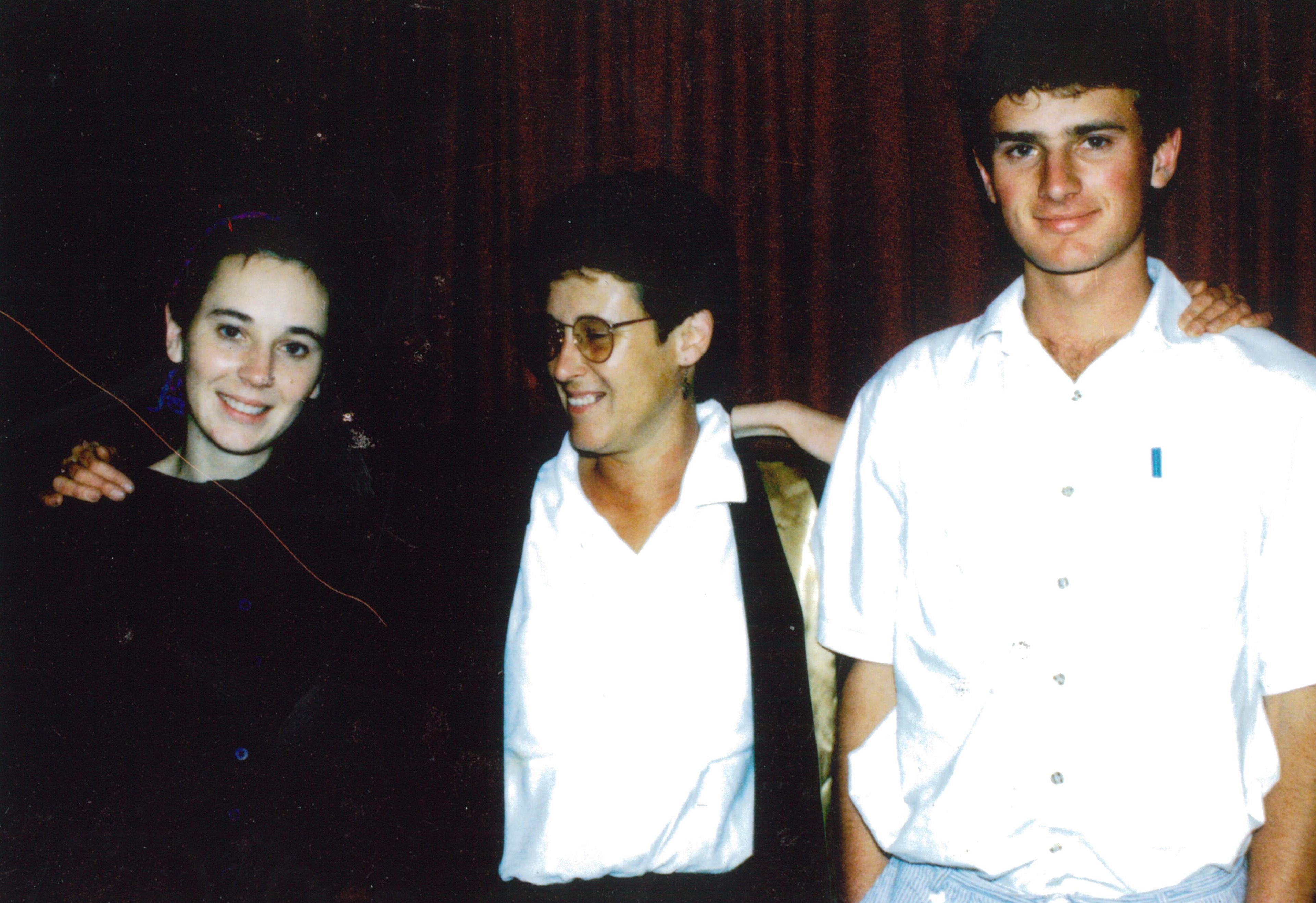

But the story begins much earlier, and is about the influence of Susan McKinnon, a woman who overcame all manner of adversity and hardship, including a violent marriage, to instil in her two children a sense of social justice, a hunger for knowledge and a commitment to give back when the opportunity arose.

“My parents separated when I was six or seven,” says Grant, who recently turned 50.

“My mother took me and my younger sister to Adelaide and it was a pretty tumultuous period, but we came through it. She worked at several cleaning jobs, built a life for us over there, and a life for herself, went back to school, finished Year 12 and went to university.”

Mrs McKinnon says it took her quite some time to matriculate. “I did a couple of subjects at a time and worked my cleaning around it,” she says. After unsuccessfully applying to study speech pathology, she completed a degree in social work and built a career in women’s health and ageing.

Politics & Society

Regenerating political leadership in a populist age

“By the time I finished the degree my children had grown up, so they didn’t reap the benefit of that apart from learning that you can study for the whole of your life.”

Grant had his challenges, too, and initially struggled to find a direction. He dropped out of university, worked in a factory in Melbourne until it closed, was unemployed, went back to study, worked as an auditor until he was sacked (“I was the world’s worst auditor”) and then set up a mobile tech company that, after a faltering start, became a text-messaging juggernaut worth around $300 million.

“As the business was starting to become successful, my mother was asking me regularly what I was going to do with this money,” he recalls. “‘You talked about making a contribution,’ she would say. ‘When are you going to start?’”

His answer was to establish the foundation in his mother’s name and commit himself to use the vast majority of the proceeds from his business to make a difference for the wider community.

In the first instance, the focus was on funding think tanks like the Grattan Institute that are committed to developing high-quality public policy. Most recently, it has been on finding ways to recognise, promote and inspire leadership.

The McKinnon Prize was launched in Canberra on November 27, 2017, with the aims of promoting strong and effective government and encouraging those who aspire to political office to reflect on the type of leader they want to be.

Sue McKinnon attended the launch, but not before showing her support for those asylum seekers and refugees who have been on Manus Island for more than four years at a rally outside Parliament House.

When Grant asked her where she had been, she told him and reminded him of the early days in Adelaide, when she would take Grant to demonstrations and he would wear anti-uranium mining badges to school.

“We’re facing a crisis of public trust in our leaders – not just here in Australia but around the world, but there remain many political leaders in Australia who are very talented and very dedicated, with a strong commitment to building a better society,” he says.

“The current crisis of trust is not just a problem for our current leaders. It makes it potentially difficult to convince the next generation of political and policy leaders to step up to help shape Australia’s future - and that is a major concern.”

Read: Emeritus Professor Judith Brett on political leadership

Nominations are invited from the public or the politician in two categories, one for established politicians and one for those who have been elected for less than five years, with the two winners to be announced at the University of Melbourne in March.

Both will receive a trophy and deliver a speech. The emerging leader will also receive a $20,000 prize to be used for professional development.

University of Melbourne Vice Chancellor Glyn Davis, who will chair the judging panel, says the aim is to recognise those leaders who have driven positive change and, in the process, encourage a national discussion about the role of politicians and leadership.

“We believe these inspirational leaders exist, and that now is the time to shine a light on what they are doing,” he says. “This what the McKinnon Prize will achieve.”

One danger is that the winners will be seen through the prism of partisan politics, and both Nick Reece and Grant Rule are acutely aware of it. “There is no doubt that the prize will be contentious, that not everybody will agree with who the final recipients are.”

But the danger has been minimised in two ways. The first is the criteria by which nominees will be judged, which responds to an argument pressed by La Trobe University Emeritus Professor Judith Brett at the launch.

“So much in the current political context rewards those who sharpen up the lines of division, when what we need is for these lines to be softened and blurred, to enable the development of a new policy consensus as Australia heads further into the 21st century,” says Professor Brett, the author of a new biography of the country’s second Prime Minister, The Enigmatic Mr Deakin.

Developed by the Melbourne School of Government with the McKinnon Foundation, the criteria require that contenders for the two prizes exhibit innovation, collaboration, courage and the highest ethical standards.

Politics & Society

Why it’s too late for Malcolm Turnbull

“We have developed criteria for what we think people should look for in their political leaders,” explains Mr Reece. “It includes that they have a vision for the community, or state or country; that they are prepared to make decisions which might not be in their short term political interests but are in the best interests of the country; and that they are prepared to collaborate with others and embrace bipartisanship.”

Judges will also be looking to recognise those who have displayed “honest, compassionate and ethical behaviour that inspires public confidence” and had an impact on one significant public policy issue, or through multiple achievements.

One way of assessing the value of such a prize is to consider which past acts of leadership would have satisfied the criteria and three come immediately to mind: the economic reforms of the Hawke government; the gun reforms introduced by John Howard after the Port Arthur massacre and the Mabo legislation of the Keating government.

The second way the University and the Foundation have minimised the potential for controversy is in the selection of the judging panel.

“I think it’s going to be terrific because the people on the judging panel are coming from such different walks of life,” says one of the judges, Oxfam CEO, Helen Szoke. “There’s a great opportunity to look at the notion of political leadership through many different lenses.”

Among the judges are two former prime ministers, John Howard and Julia Gillard; one of the country’s most highly regarded former public servants, Dennis Richardson; the chief executive of BHP Billiton, Andrew Mackenzie; and former Australian cricket captain, Adam Gilchrist.

Another is Professor Megan Davis, the director of the University of New South Wales’s Indigenous Law Centre, who was a key figure at this year’s historic Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander constitutional convention at Uluru.

“The selection panel was absolutely critical,” says Professor John Howe, the director of the Melbourne School of Government. “If we didn’t get that right, the prize would not have the legitimacy it needs, and the response has been amazing.”

The vast majority of those approached to be judges accepted, he says, and most of those who declined did so only because they could not be in Melbourne when the judges assemble to make their decisions in February.

This, Professor Howe believes, is a reflection of hunger for a focus on positive leadership across the country.

Politics & Society

A leadership merry-go-round that won’t stop

If examples of leadership worthy of nomination are needed, two of them came in the same week the award was launched: the passage of marriage equality legislation through the Senate and the passing of historic voluntary euthanasia laws in Victoria.

Liberal senator Dean Smith authored the marriage equality bill and was applauded by figures from all sides of politics after the vote, with Attorney-General George Brandis saying he knew how much stress, loneliness and hurt his colleague had endured.

The passage of voluntary euthanasia was in Victoria was just as historic and followed around 100 hours of debate over six weeks. It was a triumph for Premier Daniel Andrews, who threw his political weight behind the bill, and his Health Minister, Jill Hennessy.

But Professor Howe, whose father Brian was a reforming cabinet minister and deputy prime minister under Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, is confident that examples of inspirational leadership at a local, state and national level that have had little or no public profile will be among those nominated.

“I think there have been a few failures of public leadership in recent years on both sides of the political spectrum, but there have been good stories as well and that is what we want to focus on with this award,” says Professor Howe.

“One quality I inherited from my dad was optimism, and I think there are many people trying to make a big difference, and it’s important to highlight that at the moment when there is so much negativity about politics.”

Among those to welcome the award is Marcia Langton, who since 2000 has held the Foundation Chair of Australian Indigenous Studies at the University of Melbourne. “The malaise in Australian politics is the failure in recent years of the parliamentary leadership to embrace good policy and act on good policy for the sake of the nation,” she says.

“Some encouragement of good political leadership is just what we need.”

While the hope of Professor Howe and Mr Reece is that the award will become a national institution, Mr Rule sees it as one first step to address a major problem. “There’s a great quote from John F. Kennedy that says it’s better to light a candle than curse the darkness,” he says.

“The easiest path is to keep bemoaning the poor state of politics and do nothing about it. I believe it’s far more important to identify the things that remain good and true in our system and build on them for a better future.”

For Sue McKinnon, there is a mother’s pride in her son’s achievements and willingness to give back, and cautious optimism that the prize will make a difference.

“I am just hoping people will take a greater interest in, and have a greater awareness of, good leadership and what that can mean for Australia,” she says.

Michael Gordon is a Melbourne journalist. He won the 2017 Walkley Award for the most outstanding contribution to journalism.

Banner: Getty Images