Politics & Society

Catalonian and Scottish independence: Why so different?

Spain says it will not recognise the latest referendum on Catalonian independence – but what can historical precedents tell us about the likelihood of future autonomy for Catalonia?

Published 16 October 2017

In early October, thousands of Catalans voted in a referendum on whether Catalonia, a semi-autonomous province of Spain, should become an independent state. At the request of the Spanish government, which views the referendum as illegal, Spanish police responded to the referendum by blocking access to referendum-related websites and removing ballot boxes, as well as physically preventing Catalans from voting and firing rubber bullets at them.

The Spanish reaction prompted international criticism, but for the Catalans themselves, it is the most recent example of historic repression by the Spanish government which reached its zenith during the rule of Spain’s fascist dictator, Francisco Franco between 1939 and 1975.

But it goes further back in history than last century.

Catalonia was an independent region on the Iberian Peninsula with its own language, laws and customs, but in 1150, a royal marriage meant the region was basically bequeathed to Spain.

Various kings and governments throughout history have tried to impose the Spanish language and laws on the region. But the 19th century ushered in a renewed sense of Catalan identity, which moved into a campaign for political autonomy and even separatism. In 1931, when Spain became a republic, the Generalitat (the national Catalan government) was restored after having been dismantled in the 18th Century.

Politics & Society

Catalonian and Scottish independence: Why so different?

This came to a harsh end at the conclusion of Spanish Civil War, when the Franco regime banned the use of the Catalan language in public spaces and schools and prohibited Catalan first names. Other important symbols of Catalan identity, such as the Catalan flag and the Catalan national anthem, were also outlawed.

The Franco regime responded to public displays of Catalan identity with violent crackdowns. For example, in the 1960s Catalans were arrested for publicly celebrating their national day, La Diada, and were fined and arrested for publicly singing Cant de la Senyera (Song to the Catalan flag), a nationalist song.

In 1940, the regime also ordered the execution of Lluis Companys, the former Catalan president, who, in 1934 proclaimed a Catalan state. He was deported from Nazi-occupied France and then executed in Barcelona.

Unsurprisingly, Franco’s repression of the Catalan identity bolstered pro-independence sentiment in Catalonia. And in 1978, the region was granted a degree of autonomy once more, when democracy returned to the country.

But calls for complete independence grew steadily until July 2010, when the Constitutional Court in Madrid overruled part of the 2006 autonomy statute, stating that there was no legal basis for recognising Catalonia as a nation within Spain.

Following snap elections in 2014, the regional government backed by the two main separatist parties, held an informal, non-binding vote on independence. Eighty percent of people involved voted “yes” but Spain again ruled there was no legal basis for recognising Catalonia.

Madrid’s response to this year’s referendum is also likely to continue strengthening pro-independence sentiment among Catalans living there, as well as the Catalan diaspora, notably in Australia.

In mid-October, Catalan president Carlos Puigdemont, signed a declaration of Catalan independence which the Spanish government immediately dismissed. A short time after the declaration, Mr Puigdemont suspended its implementation saying he wants a negotiated solution with Madrid.

Politics & Society

Unified no more: Spain spirals towards constitutional crisis

Despite these renewed calls for dialogue, the proposed negotiation puts the Spanish government in a difficult position – as Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has already said he will not engage with the Catalan leaders until they drop their plans for independence.

If Mr Puigdemont does implement the independence declaration in the near future, it would be symbolically significant for the Catalan independence movement and may embolden other pro-independence movements in Spain and Europe.

However, history indicates that unilateral declarations of independence by separatist groups and subsequent attempts to implement them have largely been unsuccessful.

And it’s unlikely that Mr Rajoy’s government would accept the implementation of the declaration. Catalonia is one of Spain’s wealthiest regions, but there is also the concern that Catalan independence could reinvigorate the unsuccessful and violent pro-independence movement in Spain’s Basque Country previously spearheaded by the terrorist organisation ETA.

If Mr Puigdemont does attempt a move toward independence, Mr Rajoy could respond by activating Article 155 of the Spanish constitution which enables the Spanish government to suspend autonomy and impose direct-rule in autonomous regions if they act against the interest of Spain.

It would, however, be unwise for Mr Rajoy to take such action as it would further tarnish Spain’s international reputation and weaken its current campaign for a seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council. But also activating Article 155 is likely to fan anti-Spanish and pro-independence sentiment in Catalonia.

Time will tell whether the Spanish government continues to take a heavy-handed approach towards Catalan demands for independence. If history is anything to go by, it is only going to continue.

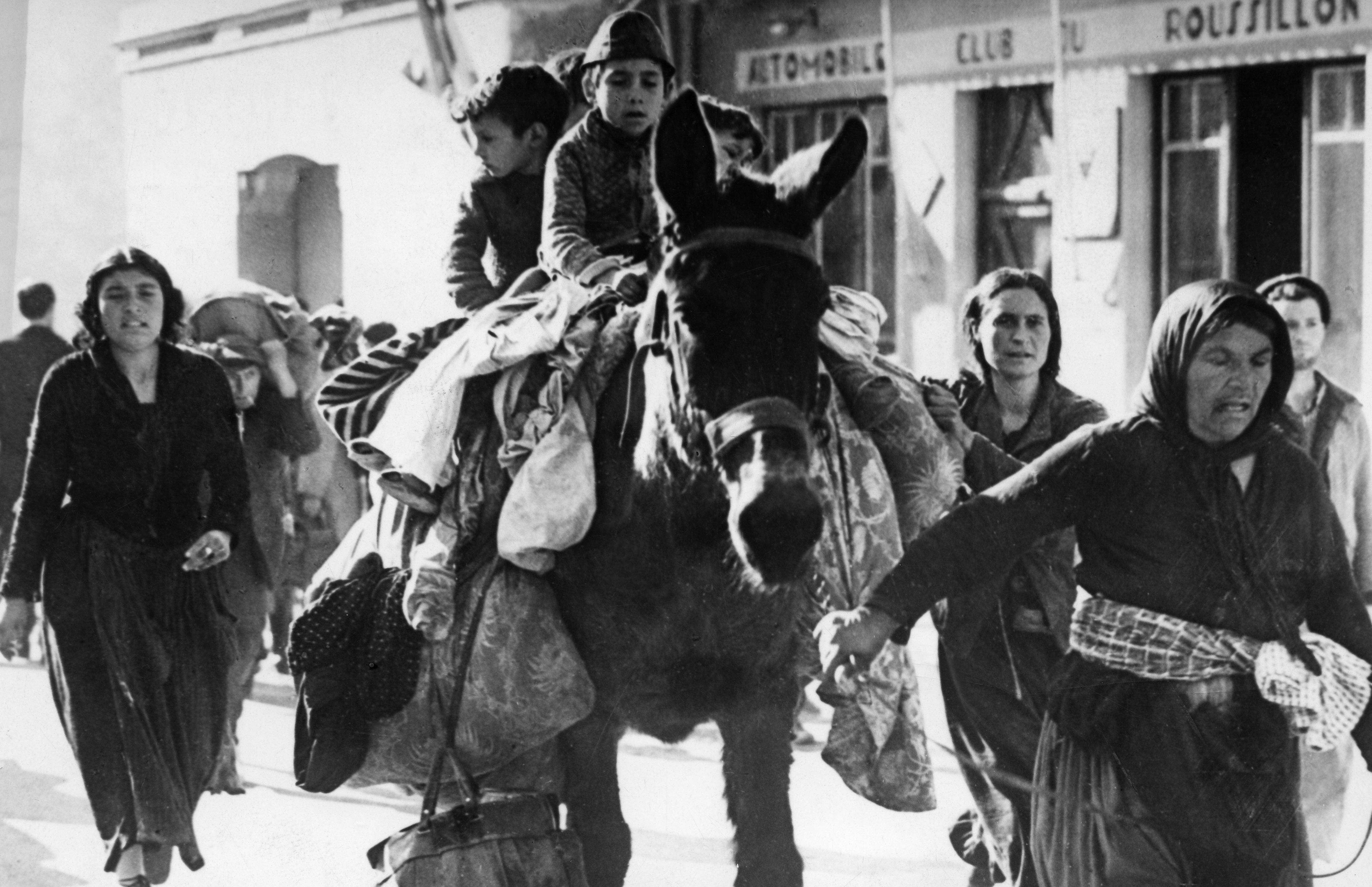

Banner image: Left-wing Catalan Nationalists demand autonomy for the region with a demonstration in Las Ramblas, Barcelona, 20th February 1936. (Photo by FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)