Politics & Society

Should we work with or turn off AI?

A Federal Court ruling that the Australian government’s ‘Robodebt’ system is unlawful shines a much-needed light on what the law actually says

Published 4 December 2019

It should be no surprise that the Federal Court last week ruled that the Australian government’s scandal-plagued automated welfare-debt collection system was illegal.

The real surprise is that the system, colloquially dubbed “Robodebt”, was ever allowed to happen in the form it did.

Robodebt, officially called Online Compliance Intervention, ended up wrongly pursuing thousands of welfare clients for debt they didn’t owe, sparking a class action.

But if the government had looked properly, it would have found a significant body of legal decisions to suggest the system was not following internal guidance, or offering protections (such as the burden of proof or administrative procedure) required by the law.

Some have already expressed concern that the algorithm-driven system breached Australian law on seven counts, and it is questionable whether it is appropriate to ever use algorithmic decision-making under certain circumstances.

Politics & Society

Should we work with or turn off AI?

Instead of calculating fortnightly amounts paid based on notified income, the Robodebt algorithm spreads recipients’ income over the entire year, and then calculates benefits.

This provided an entirely different outcome for some recipients, especially those with irregular incomes.

Many received letters advising that they had a debt to repay, with interest, and if they disputed the calculation, the burden of proof was placed firmly on the recipient.

A Senate enquiry is now underway into the long-term effects of this approach, but it is difficult to imagine any scenario that this calculation was used for any purpose other than to intimidate and demean.

Recently, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Philip Alston, in his warning about the risk of a “digital welfare dystopia,” singled out Robodebt as one of the leading examples of how much human and reputational damage can be caused by bad design.

But let’s take a quick look at the law.

There are at least 11 Australian Government agencies using automated decision-making systems, and we know of 29 pieces of individual legislation that permit automated decision-making at present.

In 2004, the Administrative Review Council provided a report on Automated Assistance in Administrative Decision-Making and, in 2007, the Commonwealth itself launched a ‘Better Practice Guide’ with a Summary of Checklist Points for Automated Assistance in Administrative Decision-Making.

Sciences & Technology

What were you thinking?

What this legislation makes clear is that the use of automated decision-making by the Australian Government is not binding under law.

This was upheld by the full Federal Court in the recent case of Pintarich v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCAFC 79, where the majority of Judges held that “no decision was made unless, accompanied by the requisite mental process of an authorised officer”.

This means that, in the Robodebt case, while the onus was put on the welfare recipient to prove they didn’t owe a debt, in actual fact, if they disputed the calculation they shouldn’t have even been advised that there was any debt until an ‘authorised officer’ had reviewed their case and found that a debt was owing.

In addition, where an automated system is used for decision-making, the Australian Government needs to make public that this kind of system is being used and ensure that the algorithms are explainable.

Australian Federal Court justice Melissa Perry noted in a 2014 speech that “[i]n a society governed by the rule of law, administrative processes need to be transparent and accountability for their result facilitated”.

The onus then is on the Australian Government to advise where it is using automated decision-making and provide a disclaimer that an automated decision isn’t binding.

The Government now needs to provide evidence of how it will meet these standards prior to using any future automated decision-making.

It should also develop best practice for ensuring compliance with existing administrative and other laws.

Finally, it needs to be recognised that automated decision-making is not always suitable, particularly in circumstances that require human discretion.

Politics & Society

Holding a black mirror up to artificial intelligence

The government needs to be aware of the potential of these systems to embed existing power structures and have unintended consequences.

Nearly three years ago, the Commonwealth Ombdusman raised concerns about the transparency and usability of Robodebt, noting that the accuracy of the system was dependent on a recipients’ information being complete.

And yet it took another two years and pending litigation for changes to be made to how the Online Compliance Intervention was implemented.

But as a matter of urgency, in response to the Federal Court decision, the Australian Government needs to establish an open and fully representative oversight body to ensure justice is fully and quickly delivered to its past victims and that no future debts are asserted other than in proper compliance with Centrelink’s legal obligations.

The Australian Government has the opportunity now to follow advice provided to it in 2004, 2007 and 2017, and seek to establish best practice – rather than be the example used as a warning to the United Nations.

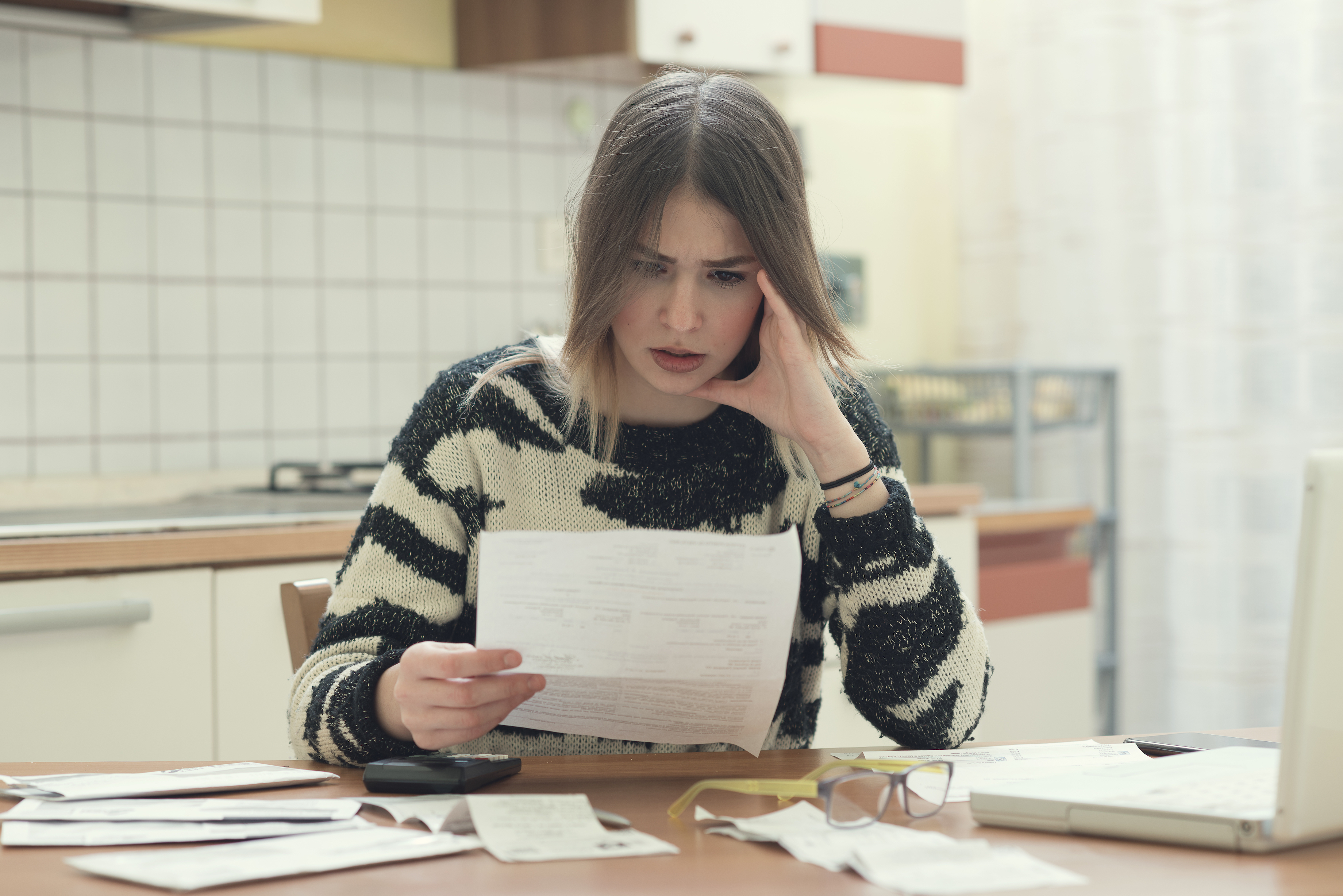

Banner: Getty Images