What street gangs can teach us about political leadership

A forgotten classic on sociology shows parallels between powerplays on the street and in the party room

Published 23 June 2016

In about 1515, Niccolo Machiavelli wrote in The Prince: “I hold it to be true that Fortune is the arbiter of one-half of our actions, but that she still leaves us to direct the other half, or perhaps a little less.”

In 2015, Malcolm Turnbull said: “What you’ve got to do is recognise that you don’t control everything for a start, you’ve got to play the cards you’re dealt, the hand of cards you’re dealt, as best you can, and that’s what I always seek to do.”

Over half a millennium later Machiavelli’s words still echo in the instinctive thoughts and responses of leaders in Western democracies.

Machiavelli, a proud Florentine, likened political fortune to the workings of a great river – the Arno, one might suspect – which periodically bursts its banks, taking all human construction before it.

The wise prince takes precautions by building levees, but none can withstand Fortune’s ultimate authority when the river is in full flood. A 50-50 deal is the best leaders can hope for.

The path of Australian politics over the past 20 years suggest Fortune continues to toy with the destiny of leaders.

The last two Prime Ministers to win elections were both removed from office in their first term. Even the most long-lived can see fortune suddenly reversed – as John Howard experienced when he lost his seat to Maxine McKew at the 2007 election. The pattern on both sides of the aisle sees destabilisation from within the party room.

What does such volatility tell us about leadership itself? Before and since Machiavelli, philosophers, scholars and leaders themselves have mulled the secrets of success and failure when seeking to lead others.

Our own times see academic literature proposing dozens of theories and sub-theories of leadership. Yet no one has found an accurate law or formula that predicts who will become a leader, or how long they will endure.

Leadership depends as much on the characteristics, needs and moods of the group to be led as on the attributes of the leader. To start the study of leadership with a leader’s attributes may be to begin in the wrong place.

This realisation struck me with some force years ago when, in the course of some research on the choice of political leaders, I came across a now obscure literature on American gangs in the first half of the 20th Century.

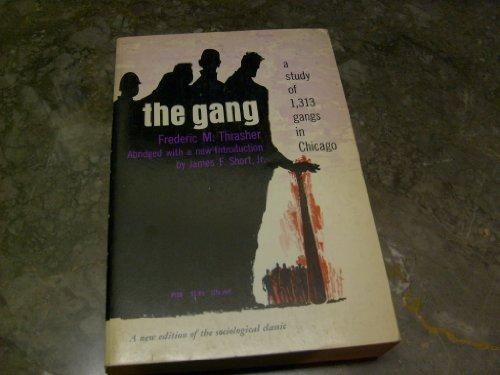

A book called The Gang: a study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago is a forgotten classic written in 1927 by a sociologist with the glorious name of Frederic M. Thrasher.

The Gang provides a real insight into leadership. It tells us that leaders matter less than conventional wisdom suggests. Leaders are chosen for a moment and then discarded. Leadership is less a science than a transitory play of luck.

For leaders, and would-be leaders, Frederic Thrasher’s forgotten book is a sobering reminder of the randomness through which leaders are chosen and allowed to operate.

In studying street gangs Thrasher wanted to answer a single, important inquiry: who becomes the leader of a gang, why, and what does this tell us about the nature of leadership?

Thrasher began with an assumption that physical prowess would be the principal characteristic of gang leaders, along with daring and a certain ruthlessness.

Instead, Thrasher found that while some gangs valued prize fighters and others daredevils, many preferred more unexpected leaders – desperadoes, puritans, politicians, ‘brains’. Some gangs preferred imaginative boys who could think up ‘things for us to do’, others the best card sharp or the most audacious thief.

Thrasher even encountered a boy with a serious disability leading an athletic street gang.

Even with knowledge of the culture and history of a particular gang, Thrasher could not predict who might become the next leader.

The succession was rarely obvious, even to those within a gang.

Even when boys bullied their way to a leadership role through size and aggression, they found their tenure ‘always uncertain’.

In interviews with gang members, Thrasher discovered few could articulate their reasons for preferring one boy over another as leader.

The gangs were unreflective about their leaders, sometimes unaware of the ‘natural leaders pre-eminence among them’ and often found it difficult to identify why a specific boy was admired as their leader.

Thrasher concluded that a leader ‘grows out of the gang’, by providing the qualities it requires at a particular time. What’s more, the leader only stays in the job while the gang needs his particular set of skills or attributes. He wrote:

No matter how great the leader … his tenure of power is never certain. Some change in the personnel of his gang or in the situation … may bring his rule to a speedy end. He makes mistakes; the gang loses confidence in him, and he is “down and out”.

The democracy of the gang, primitive though it may be, is a very sensitive mechanism, and, as a result, changes in leadership are frequent and “lost leaders,” many.

Parallels with australian political leaders

Where Frederic M. Thrasher went, others followed. In 1943, William Foote Whyte published a study of Street Corner Society, observing street gangs in Boston.

Whyte confirmed the essence of Thrasher’s observations about gang leadership, and added a couple of his own. For example, he observed that leaders of street gangs ‘always gave out more money and favours than they received’.

Whyte showed that gang leaders cannot rule solely through domination of the strongest. Rather there is a more loyal relationship between leaders and led.

There are interesting parallels with political party leaders in Australia.

An analogy is only ever an analogy, but the gang example can be useful in thinking about political leadership as well. Here too much depends on the consent of the governed and the leader must be right for the times.

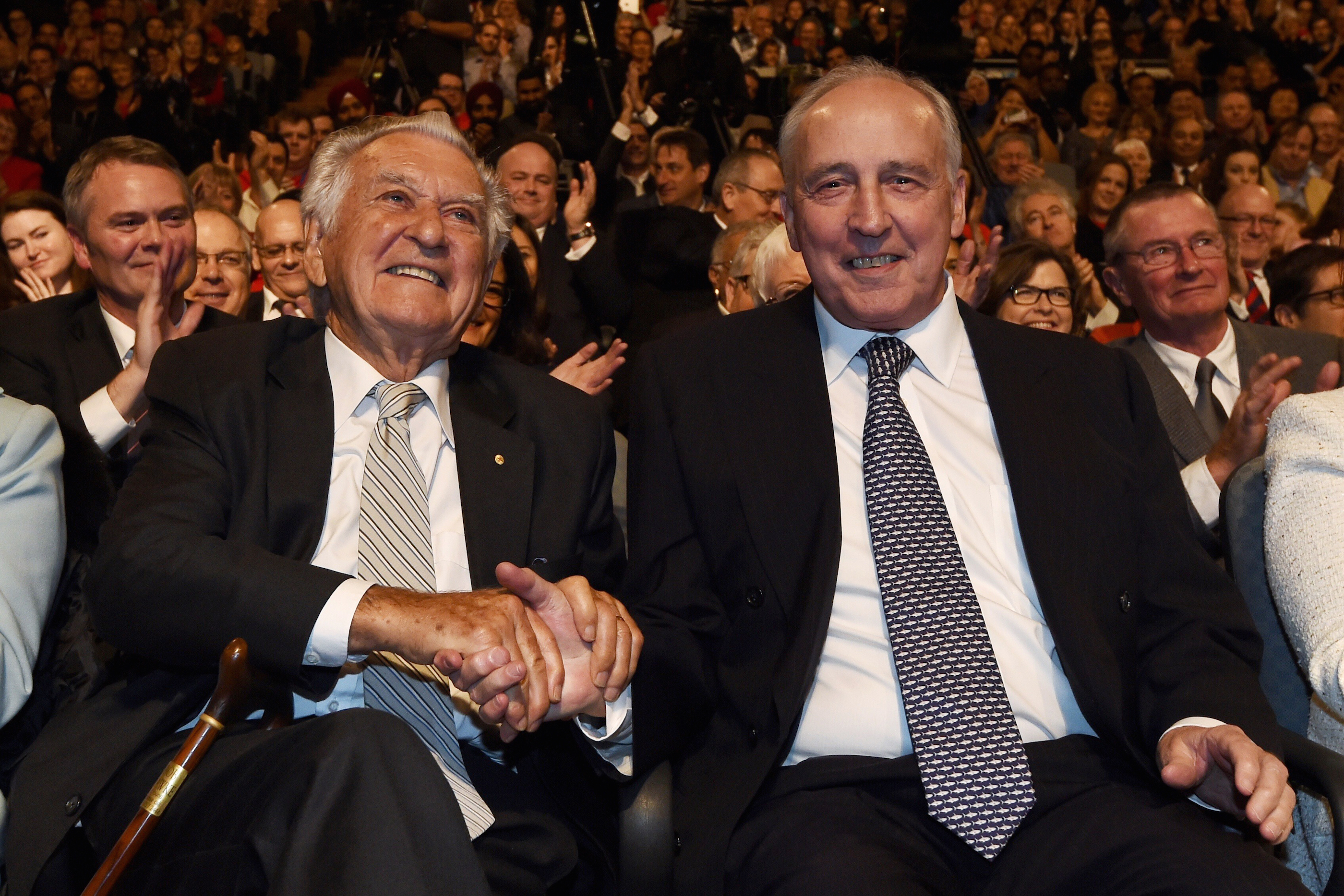

One of the most dramatic examples for contested leadership of the Labor gang began with a speech about leadership, Paul Keating’s famous Placido Domingo speech of 7 December 1990.

This triggered a year of leadership instability in the ALP, which culminated in Keating replacing Prime Minister Bob Hawke, a man who had once achieved extraordinary electoral popularity.

On the face of it, this was an unlikely outcome. Focus group research found that Keating was regarded as ‘arrogant, cold, aloof, and gratuitously insulting’ – not traits appearing in many leadership manuals.

But Prime Minister Hawke increasingly lost the confidence of the Labor gang, even after the first Keating challenge, in June 1991, failed 44 votes to 66.

The Coalition’s Fightback! package is seen as the culminating reason why Labor lost confidence in Hawke. When the Opposition moved to have Fightback! debated in the Parliament, the backbench realised Hawke did not have the confidence or skill to tackle the Opposition. A man who, in the 1980s, regularly doubled the Opposition Leader’s opinion poll rating as preferred Prime Minister, slipped behind his opponent.

In the circumstances, the particular leadership qualities of Paul Keating were right for the times. He could offer bold alternatives to the Coalition’s audacious plan.

He had the forensic skill to find Fightback!’s weak points and turn them into political liabilities for the Liberals. Keating won his second leadership challenge in December 1991, 56 votes to 51.

However, Keating’s leadership attributes probably would not have been right for Labor earlier in its term of office.

Hawke had taken some of the hard edge off Keating’s policy agenda, and provided a more consensual balance to his Treasurer’s sharp parliamentary tongue. For a long time, Hawke’s leadership had been a major asset for Labor.

Nor were Keating’s leadership attributes right for 1996, when he led Labor to compelling defeat.

But the leadership judgment made by the Labor backbench in December 1991 was the right one. Paul Keating led them to victory in 1993, an election few thought that Labor could win.

Our language suggests we believe Prime Ministers can shape their time – the Keating era, the Howard era, the Rudd-Gillard era, the Abbott-Turnbull era and so on – but this terminology is at odds with reality.

Within political parties, the parliamentary leader, even if Prime Minister, possesses little direct power. They are instead subject to the will of their party. The leader of a political party is not CEO of the party or its chairman, but instead, perhaps, something like the leader of a party gang.

Such leaders have limited capacity to control their own destiny. They serve at the mercy of the group they lead. Fortune, that raging river, is never far away.

*This article is adapted from From Machiavelli to Malcolm Turnbull: A Great Leaders Masterclass lecture delivered at the Centre for Workplace Leadership, University of Melbourne, on April 28.

Banner: Miramax

*This article was co-published with Election Watch.