Health & Medicine

From life in the zoo to breakthroughs in the lab

Lupus affects millions of people worldwide, now researchers are working to take the next step in treating the disease without ‘turning off’ the immune system

Published 9 May 2019

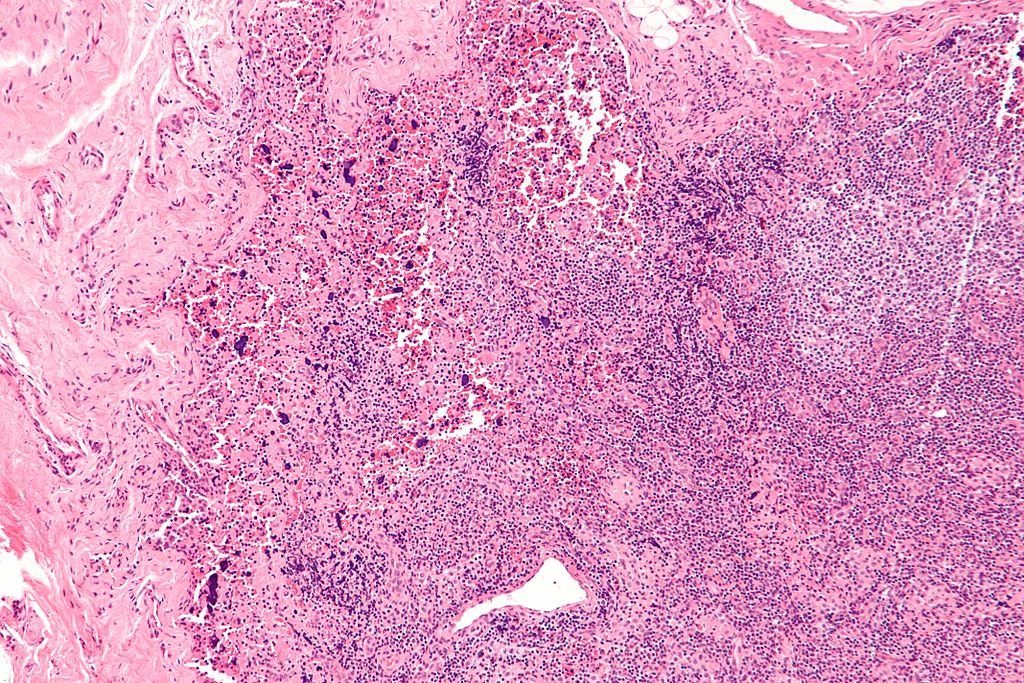

Debilitating fatigue, a trademark ‘butterfly’ rash across the cheeks and nose, and the risk of kidney failure – lupus is a severe disease where the patient’s immune system attacks their own organs and tissues.

There is no cure.

More than five million people worldwide are living with a form of lupus – most are women; but men can carry the burden of more severe symptoms.

It starts in the prime of their life, during the 20s and 30s, the symptoms are lifelong and worsen during ‘flare events’.

What’s more, it’s incredibly difficult to treat. In fact, just one new treatment has been approved in the past 60 years – thanks to the fundamental discoveries of Professor Fabienne Mackay, head of the School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Melbourne. And Professor Mackay’s laboratory remains at the forefront of global lupus research efforts.

Health & Medicine

From life in the zoo to breakthroughs in the lab

On World Lupus Day – a national awareness day highlighting the fight against this unpredictable and commonly misunderstood disease – we can look at what we do and don’t know about lupus, and the current research and development going on in the search for new treatments.

In the ‘90s, Professor Mackay led a team at Biogen Idec – an American multinational biotechnology company – that made critical discoveries laying the foundation for the development of the only approved pharmaceutical therapy in the last six decades.

Developed and trialed on thousands of patients by pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and biotechnology firm Human Genome Sciences, the drug was first approved in the US in 2013 and Australia followed, approving it in 2014.

Although not a cure, the treatment helps patients manage their symptoms by inhibiting B cell activating factor, known as BAFF, the role of which Professor Mackay originally discovered.

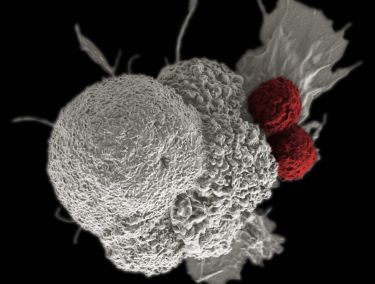

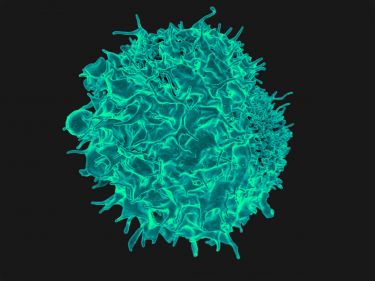

BAFF is important for ‘feeding’ young B cells, which can then ‘grow up’ to help defend our body from infections and cancers. While BAFF is essential to a healthy immune system, abnormally high production of BAFF has been linked with the development of lupus and other autoimmune diseases.

“It was an incredibly exciting discovery,” recalls Professor Mackay.

Health & Medicine

The cells giving our immune system more punch

“It enables B cells, which are a type of white blood cell, to make antibodies that are essential to creating a healthy immune system. However, too much of this BAFF factor can cause a person to develop autoimmune disease, particularly lupus.”

However, challenges remain with available treatments.

“Treatments for Lupus are either toxic and/or compromise the immune system,” she explains.

“We are developing new therapeutic strategies that are effective at stopping lupus in experimental animal models, without compromising vital immunity needed to fight infections.”

Dr William Figgett, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity who works in Professor Mackay’s lab, has been focusing on the control-mechanisms of B cells.

He used that understanding to develop a novel, targeted treatment for lupus, which adds important benefits to preserving natural immunity.

“It’s a more specific treatment, which means less issues with side-effects and loss of immunity. And so, the patients’ immune systems will be better able to protect them from other complications” says Dr Figgett.

Health & Medicine

Tapping into the power of unusual white blood cells

Dr Figgett has worked closely with the University of Melbourne’s Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Associate Professor Tony Velkov, Dr Elena Schneider and Dr John Karas) to synthesise and validate new therapeutics, which are more precise at blocking the progress of disease without compromising the immune system.

“Our strategy is different to the prevailing one – since our objective is not to shut down the immune system, but to specifically stop disease while preserving as much natural immunity as possible,” he concludes.

One of the main difficulties in applying treatment is that lupus is not just one disease, but a syndrome.

Doherty Institute researchers hope to change that.

Dr Figgett uses a sophisticated big data analysis of the genetics of many patients with lupus, enabling him to stratify patients into distinct subgroups with different gene activity signatures.

“The disease is different for each patient. This means although a treatment might work well for some, the response in others is unpredictable. By understanding more about the main differences between patients, we can identify different groupings of patients - and perhaps find out particular treatments work really well in some kinds of patients,” says Dr Figgett.

Health & Medicine

The immune legions fighting Legionnaires’ disease

Whether some subgroups respond better to some treatments is the next step in potentially validating these stratifications to predict which treatment should be used with which type of patient.

While researchers continue their work to create new treatments without ‘turning off’ the immune system, World Lupus Day calls on the community to join the fight against lupus.

Banner: Shutterstock