What will the America First Directive mean for international climate policy?

President Trump appears to be aiming for a more insular America. Here we explore how a lack of US participation could affect global efforts to combat health crises and climate change – and where we might see a glimmer of hope.

Published 23 January 2025

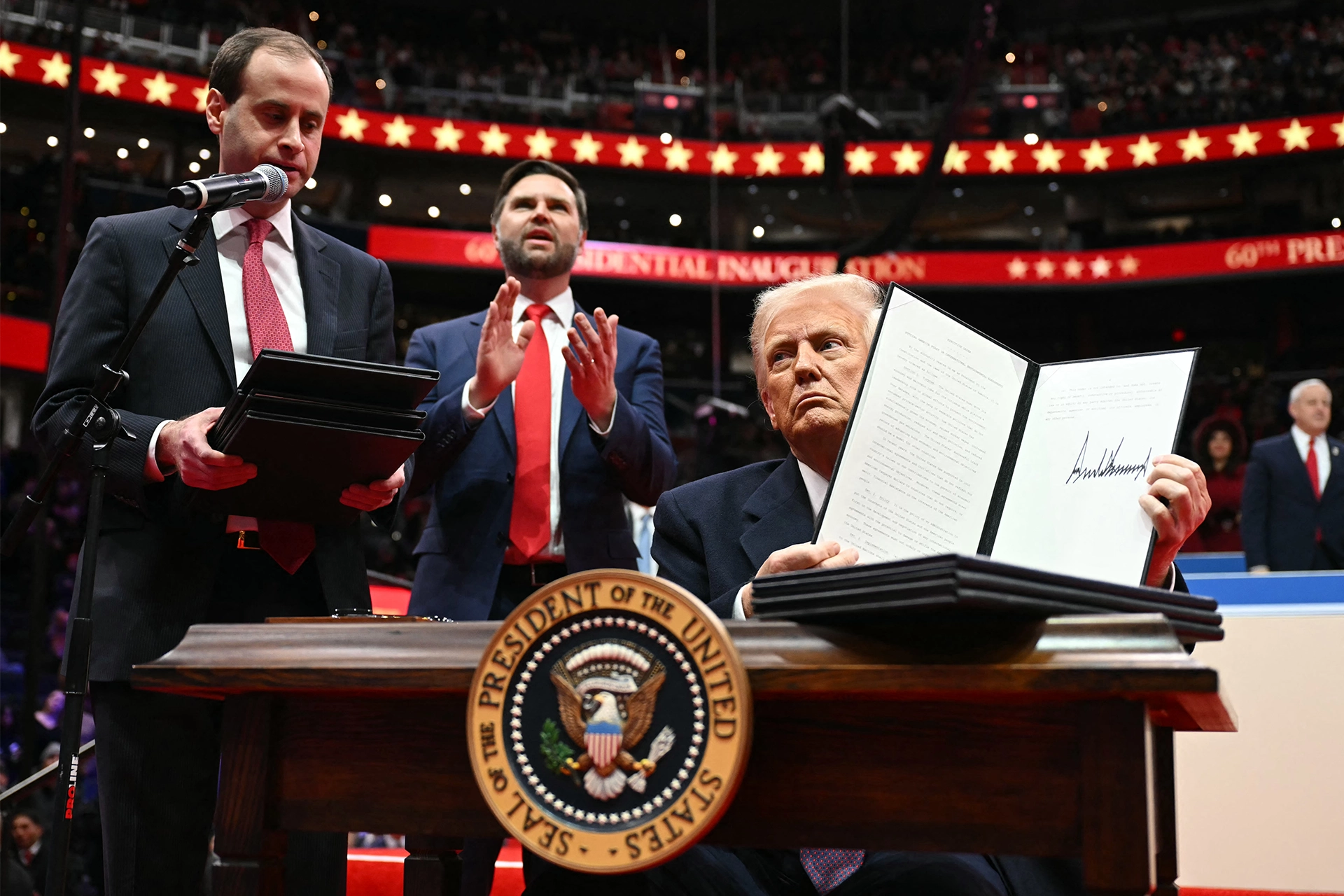

On the first of his 1,461 days in office, President Trump hit the ground running, signing a series of executive orders with a range of sweeping implications for US domestic and international policies.

The orders emphasised the increasingly inward-looking – and even isolationist – shift in popular US politics, with many focused on removing immigration rights, down-sizing climate and green energy investment, and abandoning cooperative international efforts to address global threats.

Two of these notified the United Nations (UN) of President Trump’s intention to withdraw America’s participation and funding from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Paris Agreement.

While withdrawal from each of these takes a year, during which time agreed funding must be provided, the long-term impacts on the international community are hard to deny.

We explain here how a lack of US participation affects global efforts to combat health crises and climate change – and where we might see a glimmer of hope.

Increased pandemic threats

Arthur Wyns, Research Fellow, University of Melbourne, and former climate change advisor to WHO

President Trump’s intention to withdraw the United States from the WHO will leave the most vulnerable people and communities out in the cold.

By leaving the UN’s health agency, the US would no longer be part of the new global Pandemic Treaty, which is being negotiated this year and is meant to prepare the world to better withstand future pandemics.

The country would also become a mere observer at the World Health Assembly, which convenes Ministries of Health every year.

Most importantly, the US would be cut off from the global health information system that WHO provides, which detects disease outbreaks around the world, supports countries in producing new vaccines and much more.

In other words, the US would be putting on a blindfold to global health threats.

If the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us anything, it is that we need global collaboration and solidarity if we want to address the global health challenges of our time. A country cannot isolate itself from a pandemic – something Australia knows well.

I’ve had the privilege to work for WHO for several years, supporting countries around the world to prepare their health systems for the growing health impacts of climate change, including extreme heat, wildfires and shifting infectious diseases.

It was humbling to contribute to the global effort to protect the health of millions from climate change, but terrifying to be confronted with the unmet needs of so many countries and communities.

Health & Medicine

Could climate change bring malaria back to Australia?

Our colleagues from the Ministry of Health in Malawi, for example, could not fix their health facilities fast enough to keep up with the devastation caused by cyclone, after cyclone, after cyclone.

As the US now disengages, and its funding to WHO and other global health efforts dries up, it pains me to think of the people and communities in low- and middle-income countries that will suffer the consequences.

Nobody wins when the US turns its back to the global health community.

Clearing the way for greater climate cooperation

Rebekkah Markey-Towler, Research Fellow, Melbourne Climate Futures

In his inaugural address, President Trump declared that America will ‘drill, baby, drill’.

As well as notifying the UN of his intention to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement, he withdrew from any other agreements made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), revoked any financial assistance under both the UNFCCC and the US International Climate Finance Plan.

The Paris Agreement is the international agreement that aims to keep global warming to below 2°C – pursuing 1.5°C, adapting to the impacts of climate change, and providing adequate finance for both.

Business & Economics

Trump, tariffs and the implications for Australian supply chains

During his last term, President Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement, with President Biden rejoining immediately after taking office.

When this latest withdrawal takes effect in one year, the US will join Iran, Libya and Yemen as the only countries outside of the international agreement.

In other energy and environment orders, President Trump declared a national energy emergency based on high energy prices and inadequate energy supply, authorised agencies to facilitate the exploration and production of domestic energy sources (including oil and gas), removed the electric vehicle mandate and revoked many of President Biden’s executive orders on energy, climate change and other issues.

So, what will the Trump presidency mean for climate change? Are we all doomed? Or are there some sparks of hope amid an ominous four years ahead?

Firstly, it seems likely that climate leadership will now come from other places within America.

For example, American city mayors and the global city network ‘reaffirmed their commitment to leading the way forward to confront the climate crisis’.

American states like California, experiencing the worst of climate impacts with the recent fires, will have to respond.

Concerned citizens might turn to the courts to seek action.

Another cause for hope is that the last time that Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement, it had very little impact on the decarbonisation of the American economy.

Solar and wind energy grew during Trump’s first term. President Biden also signed off on a series of clean energy projects towards the end of his term, with subsidies that will continue to pay out until 2032.

And as Jackie Peel, Director of Melbourne Climate Futures, writes, if the US leaves the Paris Agreement they may be a far less disruptive force for international climate action than if they stayed on in the Agreement as a party. It would be easy for the US the rejoin the agreement in the future.

We will also see continued international leadership from other countries like China and the European Union over the coming years, to fill the gap left by the US.

So, while things are definitely looking a little grim, hope for a safer climate future is not, nor can it be, lost.