Health & Medicine

The power of stories to rebel against a taboo

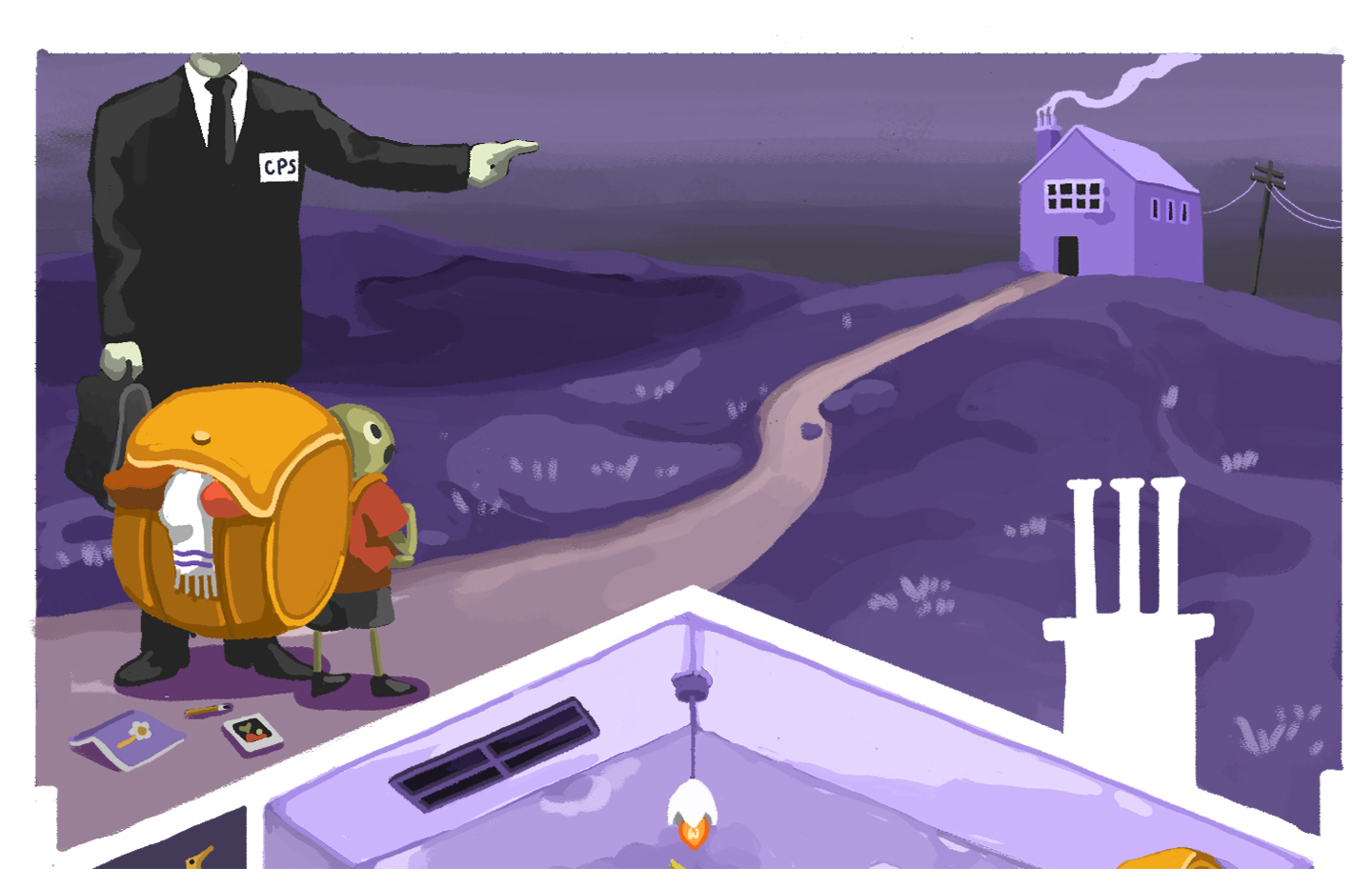

The concept of ‘home’ fundamentally shifts after a child loses a parent to domestic homicide and it can be challenging to rebuild a sense of belonging

Published 26 November 2023

Many of us associate ‘home’ with feelings of stability, familiarity and comfort.

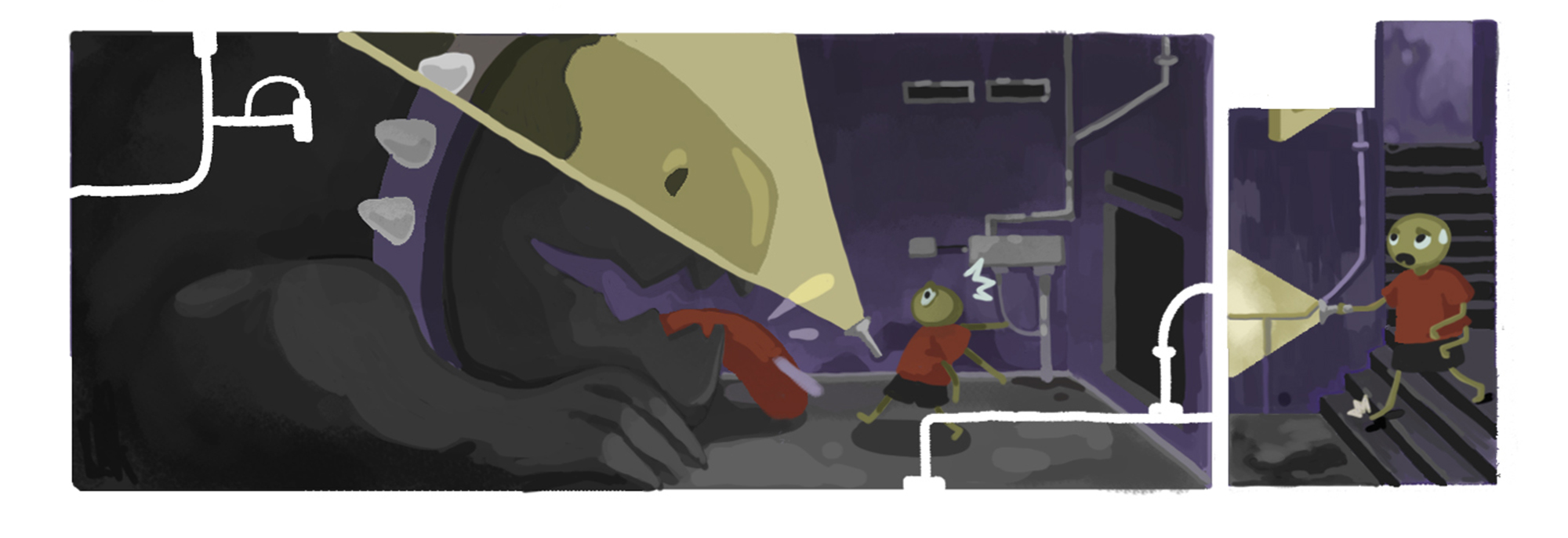

But for children who have experienced the murder of a parent – home can mean the opposite, a place of trauma and the disruption of everything once familiar.

On top of this, their concept of ‘home’ is often disrupted as they move to a new caregiver’s home, enter the foster care system or, in some cases, live with the perpetrator.

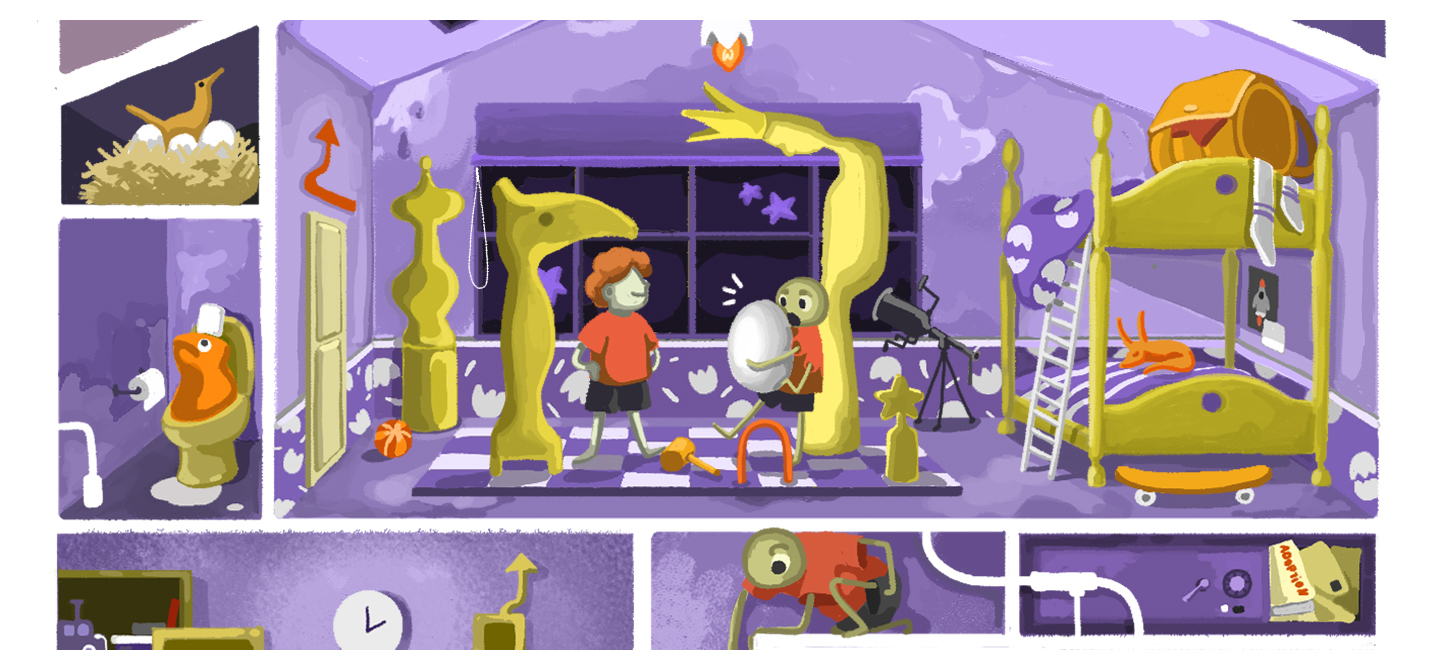

Home can be complex and challenging for these children – who not only have to potentially adjust to entering a new home environment – but also go on a lifelong journey of re-framing and re-learning what home looks like and means to them.

Previous research has highlighted the diverse perspectives and experiences of children and young people following domestic homicide – some were satisfied with where they went following the trauma, while others had mixed feelings.

What the literature currently does not tell us is how children experience home beyond the physical environment, the factors that contribute to what home means to someone and the impact these factors have on their life trajectory after their parent’s death.

Our research explores how young people and adults bereaved by domestic violence as a child experience their living arrangements.

Our interviewees felt that home was as much an emotional space as it was physical. They also experienced home as a social, ever-evolving and transient space during different phases of their lives.

Many described their own journey of unpacking unfamiliarity and discovering ‘home’ in different ways.

For example, one participant reflected on re-discovering home through the lens of home being ever-evolving and taking different forms throughout their lives.

‘So even just reminding myself of where I came from, and what I’ve been through, and whatever I’ve overcome in my life, even though it hits hard. I also look at it and go, “you know what, yeah, I did get through that. And I did go through all these scenarios. And I went through that abuse, and I went through that trauma.”

Health & Medicine

The power of stories to rebel against a taboo

We found a consistent theme of unfamiliarity when it came to feelings about home and the home environment.

Interviewees lost their sense of familiarity and, in some cases, the comfort they may have previously felt in relation to their home.

This sense of losing what is familiar often included a lack of acknowledgement of the homicide itself and of the lives that the young people lived before losing their parent.

Several participants talked about how they lost physical belongings that connected them to their deceased parent which also contributed to this feeling of unfamiliarity.

“Those memories, and those things that we valued most in our life, we had to say goodbye to and no one really acknowledged that…not only have you lost, you know, your mum, but you’re also losing everything you know”.

“We couldn’t keep what we wanted, it was just the bare necessities…we weren’t in the mindset to process what we might want [to take with us]”.

Some of the people we spoke to had been removed from their homes and were moved to a new caregiver’s home or went into the foster care system. So as children, they were not only dealing with their own traumatic grief of losing a parent, they were also navigating and trying to fit into a new home environment.

Health & Medicine

A little rhino beetle tells a story

Several talked of their experiences as a young person navigating a new home environment and the common feeling of having to hide their emotions as a way of adapting to the new space they found themselves in.

“I’ve developed how to hide my emotions and I can really quickly change my emotions within seconds’.”

“I guess I felt like that for a really long time. I didn’t talk about any of these things with anyone and there was so much kind of silence and shame around the issue.”

Young people having to hide their emotions in the new home environment highlights the stigma around domestic homicide and the internal turmoil that young people endure by feeling silenced.

While the physical new home environment could be a challenge for children, the relationships inside that home really shaped the way they processed the homicide and their loss, and who they became.

The varying dynamics between the caregiver and the child after the domestic homicide led to different experiences of home by young people.

For example, one felt that the lack of acknowledgement of the domestic homicide meant that nothing was addressed for them and they were forced to pretend as though everything was fine when they didn’t feel that was the case.

Health & Medicine

A stable place in a time of turmoil

Another felt that, even though home felt physically safe with their foster family, the feelings of loneliness were still present because they weren’t able to raise the things they wanted to talk about.

Not being able to talk freely and openly about the things they wanted to speak about was a common theme.

“No one in our family ever wanted to acknowledge that there was a problem. Everyone just wanted to sweep it all under the rug. We didn’t air our dirty laundry. We didn’t talk about anything. Everything was peachy.”

“I didn’t really feel a sense of belonging anywhere, I guess, even though I did have, you know, a foster family where I felt very safe. I think because nobody was really talking about the things that I was sort of feeling internally, and I wasn’t able to talk about it. I just felt quite alone.”

These experiences of people we interviewed also highlight the importance of supporting caregivers, who may be bereaved themselves. How best to respond to children’s emotions and grief after the homicide and support them growing up are key questions that caregivers – relatives and unrelated ones alike – can struggle with.

But with support and advice, trauma-informed caregivers will likely create a home environment that feels more free and open for children and young people. It can instil a sense of belonging within the new home environment.

Speaking with people who experienced the murder of a parent as a child helped to generate a number of suggestions that could help these children move forward in the most positive way possible.

Health & Medicine

“That weird kid without parents”

First, young people need opportunities to voice their views and wishes about their home environment after the domestic homicide, and be involved in decision-making regarding their living arrangements.

Second, caregivers need to be supported in connecting with and raising children who are dealing with traumatic grief and stigma.

When caregivers are confronted with loss themselves, because they are relatives or friends, they may need support for their own wellbeing too.

Finally, in addition to supporting caregivers, accountability of the service system when placing children in care is a key factor in mitigating any long-term negative implications for these young people.

The weight ‘home’ carries in relation to a child’s journey of working through traumatic grief, their sense of self and their relationships cannot be underestimated.

A child’s lived experience of domestic homicide is traumatic, frightening and defining. By better understanding how these children define their ‘home’ we can work towards helping them find one that is stable, familiar and comforting.

Health & Medicine

A child’s right to be heard

This article is part of a series on the impact of domestic homicide on children and young people. While there are usually one or two authors mentioned, the whole research team and several people with lived experience have contributed. The illustrations have been hand drawn by Thu Huong Nguyen (Abigail). The research report contains further information.

Are you looking for support? In Australia, good places to start are Kids Helpline, Life Line, Beyond Blue and 1800 Respect. These are all free of charge. You can also contact your doctor (GP) to discuss a subsidised Mental Health Treatment Plan, and you may be able to access counselling through your employer’s Employee Assistance Program (EAP) or your TAFE/university’s counselling services. You may also be eligible for support, counselling or financial assistance through your state or territory Victims of Crime service.

Are you keen to connect with peers? If you have lost a parent due to fatal family violence, we can connect you with peers with lived experience. Please send an email.

Banner: Thu Huong Nguyen (Abigail)