Arts & Culture

The world is run by those who show up

The high rates of Indigenous youth suicide in Australia can only be addressed if the country first changes and confronts both its historical and contemporary racism

Published 23 May 2019

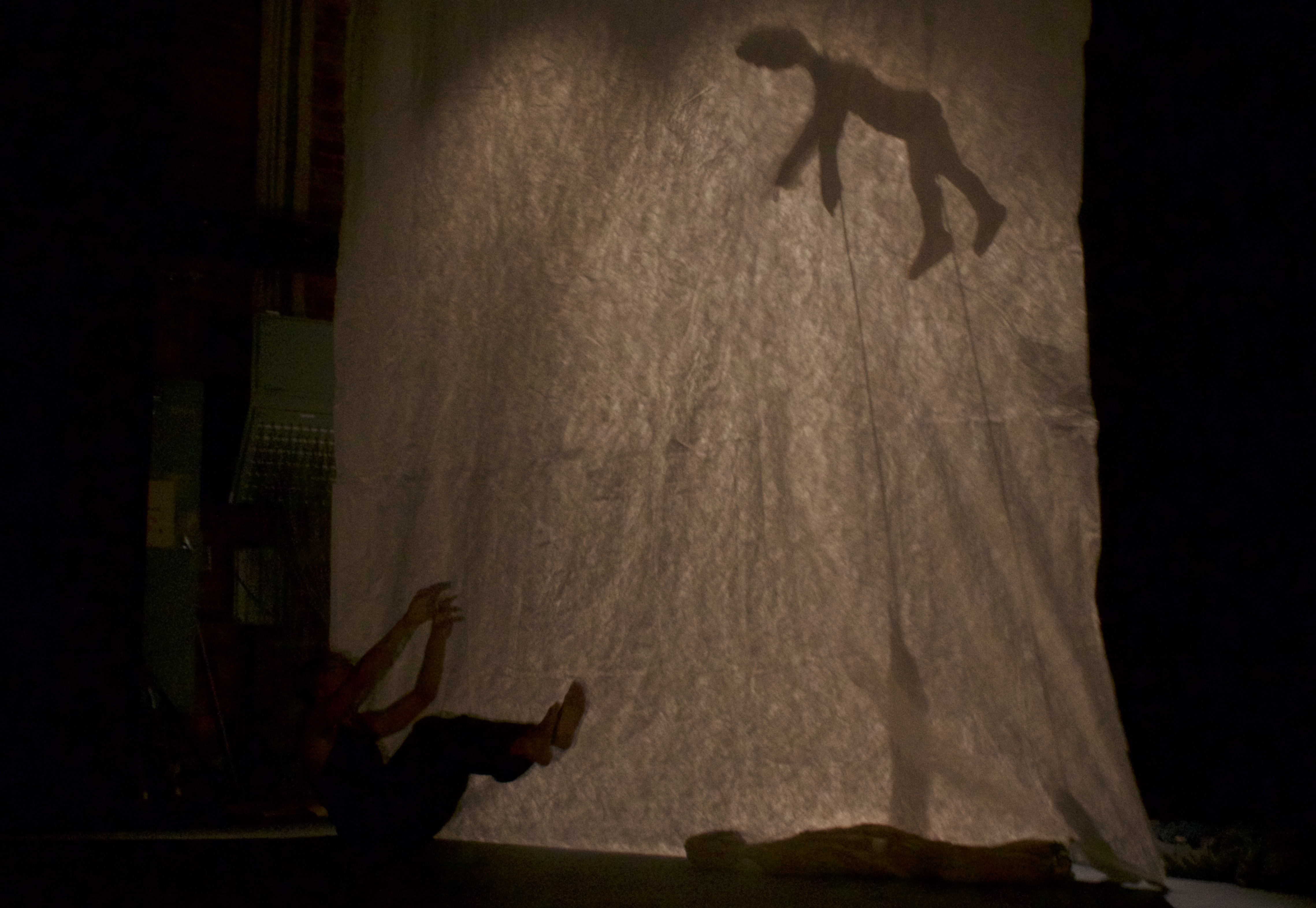

A body hangs over me.

I am so close I can feel that there is weight to the body. It seems to twitch in the stagnant air of the theatre with the last tendrils of spirit. There is nowhere to avert my gaze. I remind myself this is the point; to feel the overwhelming sickness and powerlessness Indigenous people so often feel.

I am sitting watching Jack Sheppard’s performance of The Honouring for the Yirrimboi Festival in Melbourne.

Sheppard asked his audience to sit with him and explore themes of grief, Indigenous suicide, and the transitionary healing of Sorry Business in Australia. I hold my grief in my throat.

Sheppard gently brings the body down from its hanging place caressing this dear and valued soul that has nowhere to go. Suffering from internal sickness, pervading darkness and deep-seated trauma, the weight of reality and history is too much to bear.

Sheppard tells us this body could so easily have been his.

In 2018, an Australian Senate enquiry “heard overwhelming evidence from mental health experts that in too many cases, the causes of suicide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is not mental illness, but despair caused by the history of dispossession combined with the social and economic conditions in which (they) live”.

Arts & Culture

The world is run by those who show up

Following the deaths of an alarming number Indigenous young people earlier this year, Australian leaders were urged to declare a ‘national crisis’.

We know suicide is contagious. Within groups of vulnerable people, prior suicide can facilitate the occurrence of others.

Lifeline reports the suicide rate amongst Indigenous people is more than double the national rate; Indigenous children die from suicide at five times the rate of their non-Indigenous peers.

The burden of suicide rests with our most disadvantaged. Its impact is mirrored in Closing the Gap findings across child mortality, early childhood education, school attendance, life expectancy, year 12 or equivalent attainment, reading and numeracy and employment.

Since 2005, Australia has endeavoured to ‘close the gap’ with Indigenous people. Only early childhood education and year 12 attainment are on track to be met.

Mick Dodson when he was Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Social Justice Commissioner got to the heart of the issue in 1994 when he wrote that: “The statistics of infant and perinatal mortality, are our babies and children who die in our arms…the statistics of shortened life expectancy, are our mothers and fathers, uncles, aunties and elders who live diminished lives and die before their gifts of knowledge and experience are passed on. We die silently under these statistics.”

As clinical psychologist and 2018 WA Australian of the year, Dr Tracey Westerman, has commented, given we have one of the highest child suicide rates in the world, it is staggering we don’t have clear evidence of causal relationships and casual pathways to inform statistics of Indigenous suicide.

Health & Medicine

Backing the strengths of Aboriginal young people

Both major political parties have however announced their intention to commit funding to stop the Indigenous suicide epidemic. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has directed around $A503 million into a strategy to fund research and services to boost the government’s youth mental health and suicide prevention plan.

Labor has promised effective urban and rural suicide prevention projects. Indeed, these intentions are at least ‘something’.

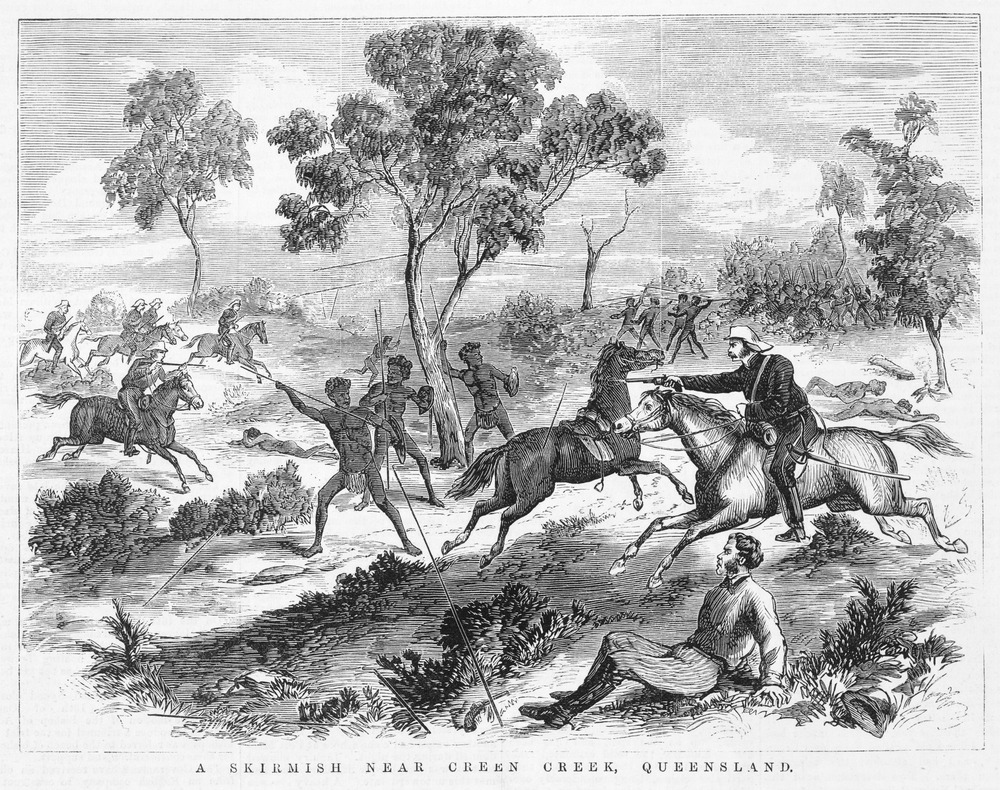

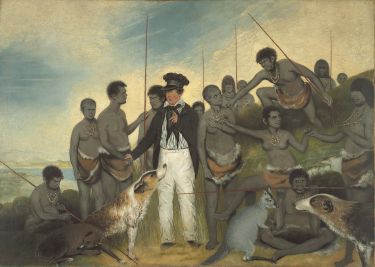

But none of these policies acknowledge the need to educate non-Indigenous people about the complex narrative of Australia’s dispossession. Invasion, frontier violence and massacre exist within living memory of Indigenous families as does slavery, stolen wages, mandatory sentencing and a myriad of racist government policies across Australia that have contributed and continue to harm.

Amid emerging evidence that the effects of trauma can be passed on from one generation to another, and given ongoing disadvantage for Indigenous people, our ‘history’ rests in our body. Its effect is inescapable, we don’t have a choice, we don’t get to decide whether intergenerational trauma affects us or not.

The Prime Minister has called his $A6.7 million plan to retrace Captain Cook’s circumnavigation of Australia a “great opportunity to talk about our history”, even though Cook’s voyage only went along the east coast.

Arts & Culture

Helping us to see when we don’t want to look

This is just a small example of the widespread casual ignorance about our colonial past that means most Australians wouldn’t be able to connect the dots between One Nation’s proposed system of Indigenous identification, requiring me and my kids to undergo DNA testing to prove 25 per cent ancestry, and the Stolen Generation strategy to breed out the colour.

This ignorance and the continued discriminatory behaviour towards Indigenous peoples, prevents meaningful action from taking place and sustaining momentum.

There is no empathy for the impact of history on Indigenous people in Australia. I only need to mention Australia Day for you to begin to get my drift.

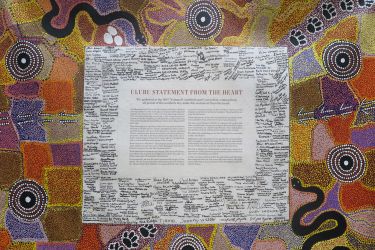

We are yet to come to terms with our entangled history, our story and how to begin a process of truth-telling.

Without fully acknowledging the cumulative effects of our history and its associated intergenerational trauma and ongoing violence towards Indigenous Australians, policies aimed at reducing youth suicide will not achieve their aims.

Australia must change.

The violence of dispossession is spilling across generations and has become a disease that is destroying our families and communities.

It is not safe to be an Indigenous person in Australia.

Politics & Society

Duty and honour at the heart of Indigenous recognition

Where can we have a frank and brave conversation about this? Without the safety of cultural authority and the healing transition of Sorry Business we move with Sheppard through grief to despair to madness to silence.

I watch as on stage Sheppard tucks his people in to dream without ceremony, dance or song. What else is there to do but sit quietly with him and begin to speak back from the dead?

If you or anyone you know needs help or support, you can call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

A version of this story is co-published with The Conversation.

Banner: Getty Images