Environment

Trump’s political climate

In order to limit global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, should countries lower their emissions’ target to meet their climate change commitments?

Published 16 November 2018

You’re having a party on Saturday night.

You’ve timed everything perfectly, starting with canapés and cocktails at 7:30pm. Except there’s one problem – your friends are always ‘fashionably late’. So, on the invitation, you put the starting time as 7pm.

That way you know most guests will have arrived by the time the party really kicks off.

Now, what if your friends are the nations of the world, the party is the Paris Agreement on climate change mitigation, and everyone is running late to lower their emissions fast enough to stop catastrophic climate change? Can we change the time on the invitation?

Attempts to tackle the growing threat of climate change seem to be continually hampered by the self-interest of people, corporations, and countries - who say they want to do their fair share but in reality do the minimum they can justify.

Because of this, the world is on track to overshoot its goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

Researchers from the University of Melbourne and University of Potsdam have quantified the self-interest of countries that have signed up to the Paris Agreement on climate change, proposing a radical solution that allows countries to act with self-interest, but still achieve the goals of the Agreement.

The goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit global temperature rise to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5°C”.

Dr Yann Robiou du Pont from the University of Melbourne’s Australian-German Climate and Energy College says the agreement is considered a landmark framework for countries to work together to avoid the dangerous impact of climate change, but there is problem with how each country’s contribution is calculated.

“Each country proposes its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), that has to be of the highest possible ambition, according to the Paris Agreement,” he says.

“Each NDC has a section describing how it is fair and ambitious, but our research, and other international reports, say these are collectively insufficient to achieve 2°C.”

Why is this? When each country has pledged to set its contribution in a way that is ‘fair and ambitious’?

Environment

Trump’s political climate

“Each country justifies how it is fair and ambitious, and according to that definition of fair and ambitious,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

This bottom-up approach can lead to self-interest, where countries pick the vision of equity that means they can make the least possible contribution.

In fact, the team built a simulation to see what global warming would be if the world followed the ambition of a single country. For example, if countries around the world made the same commitment to a Nationally Determined Contribution as Australia - the global temperature would increase by 4.5°C.

To test this idea, Dr Robiou du Pont and Professor Malte Meinshausen, who has a shared appointment with the Universities of Melbourne and Potsdam, created a hypothetical situation where each country acts to maximise its self-interest.

“We modelled the situation where each country can individually pick the least stringent of the categories of equity,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

“So, in their narrative, they can say they are doing something fair, but collectively, because of that self-interested vision of equity it would be insufficient.”

The research team used five categories of equity, broadly defined as: capability, equality, responsibility-capability-need, equal cumulative per capita and staged approaches.

The result of this modelling, unsurprisingly, is that the world will overshoot its global warming target.

“If we aim for 2°C, we get to 2.5°C,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

The catch is, this isn’t just hypothetical, it’s happening. When the researchers calculated each country’s NDC, they got the same result as their self-interest model, a likely increase of up to 2.5°C of warming by 2100.

Sciences & Technology

Key greenhouse gases higher than any time over last 800,000 years

“Collectively, it is as if the world is self-interested – keeping in mind that some countries are doing better than just being self-interested, and there are also some countries doing less than could be considered equitable, even in a self-interested manner,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

So, in other words, some of your friends arrive early, but most are late, and a few RSVP but don’t even show up to the party.

The team published their research in Nature Communications, and in the paper they suggest a radical solution – rather than forcing nations to be more fair, why not ‘change the time on the invitation’.

In other words, set a lower goal.

“If we disagree on what is equitable and let each country pick the least stringent approach, then we have to be more stringent on the collective goal,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

They calculated new aspirational goals that would allow for collective self-interest while still reaching the goals agreed in the Paris Agreement.

In fact, these results can be used in climate litigation cases against countries. Dr Robiou du Pont’s previous work has been used in a case against the EU’s institutions for failing to adequately protect them against climate change.

To keep warming below 2°C, they calculated that the world needs to agree on a 1.4°C target. To hit the more stringent 1.5°C target would require a revised 1.1°C target.

“Overall, it is very unlikely that this sharing will be adopted. Fairness is often more used as a justification for action (or inaction) than a driver,” says Dr Robiou du Pont.

“The novelty of this metric is that it can still tell which country is making a sufficiently ambitious contribution in the absence of a universal agreement of what is fair and ambitious.”

And then maybe everyone can enjoy the party.

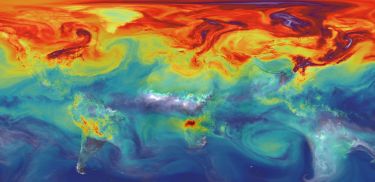

Banner: Getty Images